Where do we go from here? The Fate of Scientific and Cultural Collaborations for Young People in the Arctic

A participant from Norway in a winter school at the Petrozavodsk State University, Russia, in 2017. Photo: Anne Marit Bachman

The Arctic Institute Arctic Collaboration Series 2023

- Arctic Collaboration: The Arctic Institute’s Spring Series 2023

- Decolonization and Arctic Engagement: A Critical Analysis of Resource Development in the US Arctic

- Where do we go from here? The Fate of Scientific and Cultural Collaborations for Young People in the Arctic

- Conflict or Collaboration? The Role of Non-Arctic States in Arctic Science Diplomacy

- The Like-Minded, The Willing… and The Belgians: Arctic Scientific Cooperation after February 24 2022

- Can Arctic Cooperation be Restored?

- China-Russia Arctic Cooperation in the Context of a Divided Arctic

- From the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress to the Arctic: the Cooperation Triptych

- The EU as an Actor in the Arctic

- Vulnerability in the Arctic in the Context of Climate Change and Uncertainty

- The Ukraine War and Arctic Collaboration: Final Remarks

The saying that when two elephants fight, the grass suffers cannot be further away from the truth regarding the current state of Arctic governance. Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has had a spillover on Arctic collaboration not limited to the Arctic Council. Many states, such as the US, Canada, Norway, the UK, and those in the EU, have rained sanctions on Russia as bombs dropped on Ukraine. The Norwegian government declared a freeze on research and educational cooperation with Russian institutions, and the Arctic University of Norway stripped the honorary doctorate it adorned on Sergey Lavrov. I posit that a blanket cancellation of collaborative programs is problematic, especially those that affect young people.

This commentary shares my experiences as a former participant and organizer of cross-border educational and cultural youth events involving Norway and Russia. I highlight that the sanctions could inevitably erode progress on years of cooperation. The alacrity with which bilateral programs on cultural and educational exchanges were suspended at the start of the war raises many questions about why resources were invested in them in the first place. But first, what happens in these programs?

My experiences

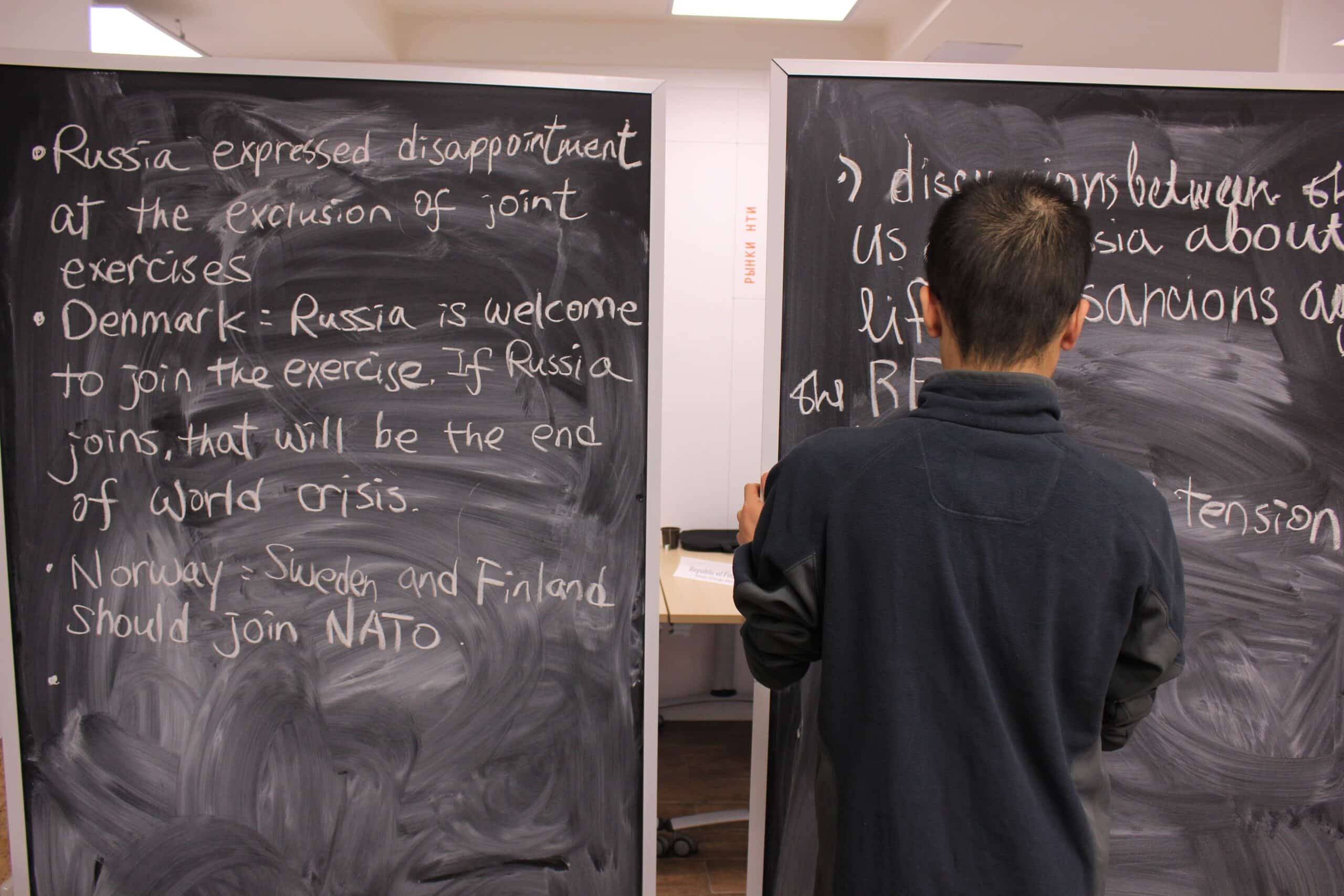

In November 2017, I participated in a five-day joint winter school on Peace and Diplomacy at the Petrozavodsk State University. An event co-organized by UiT-The Arctic University of Norway. Through the group discussions and simulation activities we had during the event, I appreciated how local history and perceptions of diplomacy from the Russian students inform their understanding of security. One of my best experiences as a student was taking part in a simulation summit of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) on a crisis in the North of Europe. My other experience relates to my work as a former trainee at Arctic Frontiers, where I oversaw the Young Portfolio in 2019 and 2020. Within the same period, I also managed the Student Forum- a program that brings young students from the Euro-Arctic Barents region and other worldwide participants. During this program, the participants attend the Arctic Frontiers conference, mingle with ambassadors, find mentors, build lifelong friendships and work together in groups on questions that impact the Arctic region. An interesting fact about the program was that the Russian Geographical Society selects Russian participants after a nationwide essay competition. With the current sanctions, the program’s original format is not practical.

Going back to the basics

The history of building bilateral agreements between Norway and Russia in the north runs deep in history; the scars from the Cold War and the victories of the Kirkenes Declaration are testament enough. For a long time, the Barents Euro-Arctic Council has recognized the importance of cooperation between its members. It notes, “The Barents’s cooperation has fostered a new sense of unity and closer contact among the people of the region, which is an excellent basis for further progress.” Unfortunately, what the Barents Euro-Arctic Council once prided itself on is now in jeopardy.

The collaboration between the two states regarding young engagements is also steeped in an intellectual tradition of peace education. In the programs mentioned earlier, stereotypical mindsets are challenged to a more open perspective, and the inclination towards conflict is replaced by the need to build trust and cooperation.

Finding a way forward

Undoubtedly, Russia’s war on Ukraine puts Norway on the alert for many reasons. However, cutting down a lot of collaborative channels, especially for young people, must be done carefully. The fact that there are currently sanctions means that the programs I once participated in are unavailable in their original shape and form. The Arctic Frontiers, for example, has had to reimagine its original idea of a student forum in 2023 without young Russian participants within the confines of the current sanctions. The Norwegian Barents Secretariat has also had to soften its requirements for providing financial support. Accepted collaborations are now limited to Norwegian and Russian educational projects if the Russian partner is an independent institution from the state.

The amendment to the criteria for financial support from the Norwegian Barents secretariat is an admission and an acknowledgement of the importance of these cross-border collaborations. It also underscores the need to constantly re-evaluate our approaches to meet our long-term strategic goals for young engagements across the Arctic. I see much utility in young Russian involvement on global Arctic forums.

Admittedly, while Russia keeps on the offensive in Ukraine, it will be unimaginable to continue with collaborations as they were before the war. Within the current geopolitical complexities we find ourselves in, we must find creative solutions to keep young Russian students on the table. One suggestion is to involve young Russian participants living in the diaspora in these educational and cultural programs. This will ensure that their experiences, competencies and insights are factored in creating the collective future we envision for the Arctic. After all, we are not whole if a part of our voice remains missing.

Larry Ibrahim Mohammed is a PhD Research Fellow at UiT- The Arctic University of Norway and a member of the Changing Arctic Research School.