Vulnerable Communities: How has the COVID-19 Pandemic affected Indigenous People in the Russian Arctic?

Field camp of Dolgan reindeer herders in Khatanga, Krasnoyarsk Krai, July 1993. Photo: Peter Prokosch

With the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the world has found itself in a global health emergency, which has caused a dramatic loss of human life worldwide and brought normal life around the world to a halt for the better part of a year. The Arctic Institute’s COVID-19 Series offers an interesting compilation of best practices, challenges and diverse approaches to the pandemic applied by various Arctic states, regions, and communities. We hope that this series will contribute to our understanding of how the region has coped with this unprecedented crisis as well as provide food for thought about possibilities and potential of development of regional cooperation.

The Arctic Institute COVID19 Series 2020-2021

- COVID-19 in the Arctic: The Arctic Institute’s Winter Series 2020-2021

- COVID-19 and Arctic Search and Rescue, our Duty to Act

- Vulnerable Communities: How has the COVID-19 Pandemic affected Indigenous People in the Russian Arctic?

- Brazilians in the Arctic: A Global Experience with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- COVID-19’s Impact on the Administration of Justice in Canada’s Arctic

- Isolation and Resilience of Arctic Oil Exploration during COVID-19: Business as usual or Structural Shift?

- COVID-19: How the Virus has frozen Arctic Research

- Rethinking Governance in Time of Pandemics in the Arctic

- Russia’s COVID Blinders: Arctic Policy Changes or Lack Thereof

- Geography of Economic Recovery Strategies in Nordic Countries

- Fly-in Fly-Out Workers in the Arctic: The Need for More Workforce Transparency in the Arctic

- Measures Taken by the Canadian Coast Guard to Respond to the Pandemic in the Canadian Arctic

- COVID-19 in the Arctic: Final Remarks

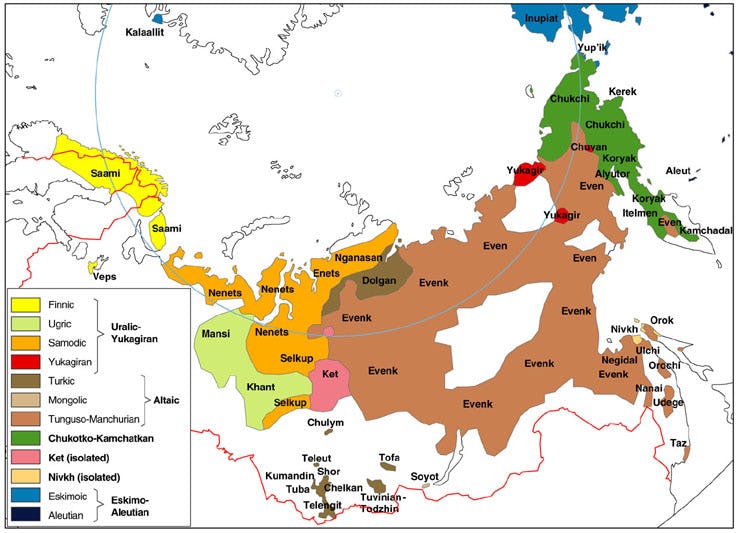

In a town of 30,000 in the Russian North in the spring of 2020, the streets of Dudinka resounded with public announcements from the local “Big Ben” clocktower asking residents to stay at home in six different languages. Five of these were local Indigenous languages – Dolgan, Nganasan, Evenki, Enets and Nenets. “Dear Taimyr residents, please stay at home. Take care of yourself and your loved ones.”

The multi-language initiative was positively received by residents as a reminder of local cultural diversity, but it was also a wakeup call that Indigenous communities in the Arctic may be the most vulnerable population group to the effects of COVID-19. The pandemic has exposed the distinct health vulnerabilities of Arctic natives and created socio-economic disruptions to their unique lifestyles.1)

In this article, the consequences of the pandemic on Russian Arctic Indigenous communities will be analyzed. The article seeks to raise awareness of how the coronavirus pandemic has affected the Russian North, one of many crises worldwide where Indigenous communities are disproportionately afflicted. This piece focuses on Russia, but many of the findings apply to Indigenous groups in other parts of the Arctic, such as the Alaska Natives whose lives and livelihoods were also disrupted. “American Indian and Alaska Native families are more vulnerable to the pandemic than U.S. residents overall due to the legacies of colonialism, racism, and the federal government’s failure to support these communities’ social and economic well-being,” writes Joshuah Marshall of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.2)

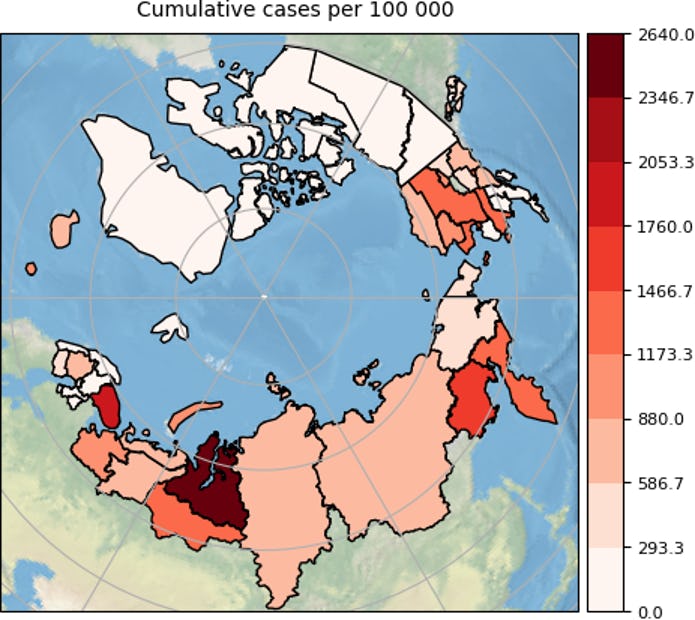

COVID-19 in the North

Isolation and small population density have allowed the Northern regions of the Arctic states to be relatively safe compared to other parts of the world, but this is not necessarily true in the Russian North. Some of the most severely impacted regions of Russia are in the Arctic. The Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug has the highest coronavirus cases per capita of all 85 Russian federal subjects and four of the top ten federal subjects by deaths per capita include the Arctic. Murmansk Oblast has a population seven times smaller than that of neighboring Finland or Norway, but the Russian region has more coronavirus cases than either country. What factors explain this great disparity?3)

It is believed that COVID-19 made its way to the Russian North by workers migrating from across Russia and the former Soviet Union to work at the industrial and extractive projects in the Arctic. One example is Russia’s second-largest COVID-19 outbreak in mid-April at the Belokamenka liquefied natural gas plant in Murmansk Oblast. At one point, twenty percent of the 11,000 employees working at the Belokamenka project operated by Novatek, Russia’s second-largest natural gas producer, were reported to be infected.4)

Controlling Belokamenka

Regional authorities responded quickly to the outbreak by limiting contact between workers and local residents, introducing a field hospital to treat hundreds of patients, and mobilizing the “Princess Anastasia” cruise ship as a floating hotel for healthy staff. However, construction continued at the plant and the epidemiological measures were hard to enforce. In a televised government meeting, the Governor of Murmansk Oblast Andrei Chibis told President Putin, “We did not stop the project, because it is important for the economy of the region and of the whole country.”5)

Activists from the Murmansk office of Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny blamed Novatek management for the ineffective quarantine regime imposed on workers in Belokamenka, which lacked an effective 14-day isolation period and adequate social distancing both during working hours and in barracks. “Novatek is obliged to compensate all expenses related to the emergency in Belokamenka because of inaction and a disregard for people,” said Violetta Grudina, coordinator of the Murmansk Navalny office.6) The situation in Belokamenka was declared under control by Governor Chibis in June. Similar stories of migrant workers bringing coronavirus and eventually spreading it to nearby communities were reported in extractive projects and mines across Kamchatka, Krasnoyarsk Krai, the Yamal Peninsula, and the Sakha Republic (Yakutia). Overall, seasonal worker migration often begets an outbreak of COVID-19. The influx of fishing crews to Alaska may be a reason for the outbreak in the U.S. Arctic.7)

Indigenous People at Higher Risk

Indigenous peoples suffer higher rates of pathogen infection compared to non-Indigenous groups around the world and throughout history. From the arrival of smallpox and measles via the first European colonizers in the Americas to the measles outbreaks in South America in the twentieth century, Indigenous groups have always been one of the most vulnerable demographic groups during such crises. In the Brazilian Amazon, Indigenous peoples die of coronavirus at a rate of 9.1 percent, nearly double the 5.2 percent rate among the Brazilian population.8) In May, the Navajo Nation surpassed New York for the highest infection rate in the United States. The Native American territory, which spans parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, is described as a “food desert” as it struggles with mal- and undernutrition during the coronavirus pandemic.9)

A report from the Centers for Disease Control found that non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN) account for 0.7 percent of the U.S. population, but 1.3 percent of COVID-19 cases. AIAN are less likely to have access to healthcare and more likely to live in poverty. As of a 2018 census, 22 percent of AIAN under 64 years old were uninsured, the highest of all racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.10) With the exception of the Sámi in the Nordic countries, Indigenous populations’ health is worse than that of their non-Indigenous counterparts across the Arctic. “Minority status may contribute to some of the observed health disparities. The majority health and social systems may not be sensitive to the needs of marginalized minority populations in their midst,” write T. Kue Young et al.11) In general, the distinct threat to Indigenous peoples around the world is attributed to the fact that they are more likely to suffer from malnutrition, poor access to sanitation, and inadequate healthcare.

Natives of Russia

Researchers from the Higher School of Economics in Moscow prepared a report for the Arctic Council that found that Chukchi, Nenets, and other natives of the Russian North are more susceptible to COVID-19 due to underlying health reasons that weaken the immune system. These include a lack of iodine, calcium, zinc, and vitamin D, and widespread alcoholism and respiratory diseases among Indigenous communities.12) Furthermore, Indigenous peoples are disproportionately vulnerable to infectious diseases because of their more than a thousand years of isolation from other societies and therefore lower resistance to foreign pathogens, a phenomenon referred to as “civilizational immunity.” Indigenous peoples of the Arctic suffered from higher mortality than non-Indigenous populations during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic and other outbreaks. 80 percent of influenza deaths during the crisis in Alaska were among Native people.13)

The distinct threat of COVID-19 to older generations poses a serious threat to the survival of ancient cultures and languages. Elders play a crucial role in passing on traditional knowledge and culture to future generations. “There are Indigenous peoples in Russia with only a few elders who can speak their languages, like Itelmens in Kamchatka,” says Gennady Shchukin, a Dolgan elder from Taimyr. “Losing these elders would risk losing whole cultures.” Elders play an important role in how Indigenous communities cope with pathogens as they pass on strategies for dealing with outbreaks such as the 1918 pandemic through oral history. Native languages were already at risk before the pandemic as fewer children were learning them from their families. “The only way to preserve the languages of indigenous minorities is to preserve their way of life,” said Grigory Ledkov, President of the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON).14)

Social and Economic Effects

Indigenous communities worldwide have been adaptive to measures combating the spread of disease and proactive in imposing a lockdown. However, besides the disproportionate health risk, there are indirect socioeconomic effects of the pandemic that arose from the lockdown. At the end of March 2020, most parts of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), Arkhangelsk and Murmansk Oblasts, and the Yamalo-Nenets and Chukotka Autonomous Okrugs were under lockdown with a strict self-isolation regime. “Infectious and mental processes are closely interconnected, especially among the most vulnerable categories of the population including Indigenous peoples,” says Dr. Yury Sumarokov from Northern State Medical University in Arkhangelsk. Indigenous people “have a higher risk of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. During a pandemic, multiplied by isolation and possible economic problems, it is certainly even higher. This is noted by us and our colleagues abroad. It is very important to know and help in time.”

For example, the physical distancing between youth and elders has distressed young children who are unable to interact with their grandparents and older relatives. Indigenous families often share crowded households with multiple generations, making it harder to socially distance and easier for viruses to spread.15) To combat the spread, Russian authorities placed restrictions on hunting, fishing, and herding, but these measures did not apply to Indigenous peoples because their survival depends on these practices. The representatives of RAIPON stressed the importance of self-supplying by traditional methods for the wellbeing of their communities.16)

“Self-isolation and unpredictable damages to demand for products have caused a great deal of damage,” says Sergey Sizonenko, Deputy Chairman of the Taimyr Duma and a Dolgan member of the RAIPON Business Council. In response, the Federal Agency for Ethnic Affairs sent an official letter to regional leaders asking them to closely monitor Indigenous peoples’ access to public services, healthcare, and essential goods. The agency recommended conducting remote monitoring and ensuring Indigenous communities’ access to food and supplies. The Yamal government then allocated 150 million rubles for additional social security payments to Indigenous people that can be applied for remotely.17)

“Since the early hours of the morning, I have been receiving messages and phone calls from rural areas expressing gratitude,” said Sergei Yamkin, Chairman of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug Legislative Assembly. “The increase in compensation for the nomadic population in lump sum payments will help tackle the pressing problems of those who live in the tundra.”18)

Disparate Impacts

The lockdown affects men and women differently. Indigenous women around the world are more likely to work in underpaid sectors and within the informal economy, and face extra burdens as they are more likely to be the caretakers of children, elders, and relatives. On the other hand, Russian Indigenous women are more likely to receive social security payments from the government due to their employment in state-funded sectors such as schools and medical facilities. In contrast, Indigenous men are more likely to work in hunting, fishing, herding, and sectors that were more disrupted by the lockdown.19)

Due to the quarantine and self-isolation, Indigenous women may suffer from an increased risk of domestic violence. “Domestic violence helplines and shelters across the world are reporting rising calls for help,” said Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women. The global surge in domestic violence is described as a “shadow pandemic.”20) “Victims of domestic violence often do not have anyone to ask for help and no institution to appeal to,” Anastasia Ulturgasheva commented of Siberian Indigenous minorities. “In Yakutia, Indigenous women constitute one of the most vulnerable sectors of the local population. If they are married into a family of a dominant ethnic group, they tend to experience further Othering and isolation.”21)

Further measures include the regional authorities restricting reindeer herders from entering settlements out of fear that they may come in contact with infected workers from the extractive projects. This policy disrupted the local economy by limiting nomadic peoples’ ability to buy food and sell their products like reindeer meat and fish. The remoteness of Indigenous settlements may have been an advantage in the early stages of the spread of the virus, but the distance from other settlements and public services exacerbate the situation for nomadic Indigenous people who subsist in the tundra.22)

“The programs dealing with the coronavirus situation depend on the financial status of the region,” said Dmitry Berezhkov, an Indigenous rights activist and former vice-president of RAIPON. “For example, in Yamal, the authorities gave notebook computers to students because of severe problems related to education in the time of the pandemic. In those regions where they have no Internet, they must study using their phones. In Yakutia, many students came to school for their assignment, wrote their homework on paper, and returned to school to submit it to teachers.”

After the onset of the lockdown, residents of the Far North asked that authorities allow nomadic reindeer herders to move between settlements and the tundra. “It is almost impossible to impose a self-isolation for reindeer herders and nomads because their work is related to grazing and ensuring the safety of the reindeer population,” said Matvey Chuprov, Chairman of the Nenets and North Indigenous Peoples Commission.23)

A Reminder of Other Crises

The pandemic is yet another global crisis where Indigenous people make up one of the most vulnerable population groups. For instance, the Norilsk disaster in May 2020, which saw a fuel storage tank spilling over 20,000 tons of diesel fuel into the environment, damaged rivers, reindeer, fish, lakes, and land, and afflicted Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods. Indigenous activists wrote a letter to SpaceX and Tesla CEO Elon Musk urging him not to buy nickel, copper, and other resources from Nornickel (the company responsible for the spill) until the corporation conducted an independent evaluation of its pollution in the Arctic. Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin oversaw a provision in September through which “extracting companies are to compensate for loss or damage to the [environment of] Indigenous peoples of Russia based on a special agreement.”24)

On the Yamal Peninsula, the nomadic Nenets people migrate hundreds of miles each year to take their reindeer to pastures. Nowadays, some of those paths and rivers across which they travel may be on thin ice due to thawing permafrost. Indigenous people are regarded as the group most vulnerable to the effects of the climate crisis in the Arctic, even though they have long known about the risks of environmental degradation on public health through their ancient knowledge and connection with the natural world. French social anthropologist Jean Malaurie teaches that the Inuit’s thousands of years of knowledge and wisdom are on par with other great schools of thought.

Looking to the future, Russia may take Indigenous issues more seriously. Russia will assume chairmanship of the Arctic Council in May 2021 and Russia’s Senior Arctic Official remarked that “Arctic inhabitants including Indigenous peoples, will of course be stressed and underlined” in the coming term.25) Russia’s official Arctic policy was updated in March 2020 with a noticeable elevation of the “improvement of the well-being of indigenous peoples in the Russian Arctic” to the level of national interest.26)

“It will be public relations for external actors, but it will hardly improve the lives of local Indigenous people,” said Dmitry Berezhkov. “A lot of training, meetings and conferences will happen, but they will discuss Indigenous culture, not rights. Those people who raise issues over ownership of land are declared foreign agents not working in the interests of the state.”

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly distressing to the Indigenous communities of the Russian North, disrupting the local economies and putting the survival of cultures at risk. The authorities’ reactive measures had varied levels of success, largely dependent on the resources of the regions. As Russia underscores the importance of Indigenous issues in its upcoming Arctic Council chairmanship and the world experiences more lockdowns to stop the spread of the virus, we will pay close attention to what comes of the rhetoric from regional and national authorities and hope for a noticeable improvement in living standards for Indigenous communities.

References