Thawing Grounds, Rising Stakes: The Importance of Including Permafrost Emissions in Climate Policy

An abandoned federal building sinks into the thawing permafrost in the Native Village of Nunapicuaq (Nunapitchuk), Alaska. Photo: Susan Natali

The Arctic Institute Planetary Series 2025

- Planetary Approaches to Arctic Politics: The Arctic Institute’s Planetary Series 2025

- Relating to the Planetary Arctic: More-than-human considerations

- To the Earth and Back: Expanding Polar Legal Imagination

- Are Arctic Viruses “Zombies”?

- Thawing Grounds, Rising Stakes: The Importance of Including Permafrost Emissions in Climate Policy

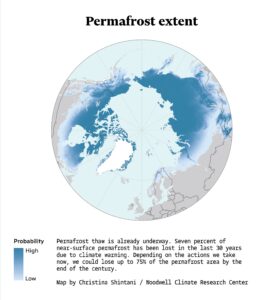

As the world races to limit global warming to 1.5°C, a critical and often overlooked climate threat looms: the rapid thaw of permafrost in Arctic regions. Permafrost1)—continuously frozen ground that covers vast portions of the Arctic—is thawing, releasing large amounts of greenhouse gases (GHGs) previously locked in frozen soils, amplifying warming at a scale that could derail global climate goals. Current international climate plans put the world on track for a warming of around 2.7°C, far exceeding the Paris Agreement’s target.2) Yet emissions from thawing permafrost remain largely absent from Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—the cornerstone of international climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. This article explores why permafrost emissions are excluded from NDCs and the consequences of this omission, and proposes concrete steps to ensure that permafrost emissions are fully integrated into future climate strategies. This substantial gap in climate policy threatens Arctic ecosystems and the global effort to stabilize the climate.

The hidden climate risks of permafrost emissions

A major blind spot in global climate mitigation strategies is the exclusion of permafrost carbon emissions from the current global carbon budget frameworks. As nations strive to limit global temperature rise and meet their NDCs under the Paris Agreement, they are failing to account for the emissions released from thawing permafrost, a serious risk to achieving these goals. Without including permafrost emissions in global climate targets, current climate commitments do not fully represent our future emissions. This creates a gap between policy and reality, which could underestimate the actual scale of emissions and accelerate warming.

Permafrost holds approximately 1.4 trillion metric tons of carbon, nearly twice the amount currently in the atmosphere.3) It has been a stable carbon sink for millennia, but this frozen ground has begun to thaw as the Arctic experiences more rapid warming. When permafrost thaws, it releases carbon dioxide and methane, potent GHGs, into the atmosphere. Once initiated, this process accelerates global warming, creating a feedback loop where permafrost thaw leads to further emissions, exacerbating the warming that triggered it.

While gradual thaw processes are somewhat predictable, abrupt thaw events, known as thermokarsts, often triggered by landslides, wildfires, or other environmental changes, can suddenly release massive amounts of carbon, leading to substantial and unpredictable emissions. Many current climate models fail to account for these abrupt thaws, resulting in underestimated future emissions.4) Recent studies suggest that about 77% of near-surface permafrost could be lost by 2100, potentially releasing massive quantities of carbon and other harmful pollutants that could accelerate global warming.5) Addressing this uncertainty necessitates the development of a more comprehensive carbon monitoring system in the Arctic to accurately capture both gradual and abrupt thaw emissions, ensuring that climate policies reflect the full scale of potential risks.

The gravity of addressing permafrost thaw goes beyond the global carbon budget. Thawing permafrost has devastating local consequences, especially for Arctic communities. As frozen ground destabilizes, it damages critical infrastructure, including homes, roads, and pipelines, resulting in billions of dollars in economic losses. Indigenous communities, whose lives and cultures are intimately connected to these landscapes, face disruptions to animal migration patterns, biodiversity, and their subsistence lifeways and traditional knowledge systems.6) Additionally, thawing frozen ground can release long-dormant pollutants and pathogens, compounding environmental and health challenges in affected regions. As these localized impacts escalate, they contribute to the global carbon cycle, creating feedback loops that worsen the climate crisis. The permafrost crisis is not an abstract environmental issue; it is a rapidly escalating threat that impacts both the global climate and the well-being of Arctic peoples and economies.

Bridging the permafrost gap in national climate commitments

Nationally Determined Contributions, established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as part of the Paris Agreement, are the primary mechanism through which countries set national emissions reduction targets to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C and no more than 2°C. The purpose of NDCs is to guide national actions and ensure that countries are accountable for their emissions, contributing to the collective goal of mitigating climate change. Nationally Determined Contributions have fostered this accountability and driven national actions. However, despite their essential role in keeping the world on track, NDCs have a critical blind spot: they fail to account for emissions from permafrost thaw. While NDCs effectively cover emissions linked to human activities like fossil fuel combustion, they largely overlook natural carbon feedbacks. This omission creates a substantial gap in global carbon accounting, undermining the accuracy and comprehensiveness of current climate commitments.

Several factors contribute to the exclusion of permafrost emissions from NDCs:

- Geographic limitations: Most countries are not underlain by permafrost, so they may not prioritize this issue in their national climate strategies. As a result, even though they contribute to global warming, countries without permafrost are less inclined to address emissions from thawing permafrost within their NDCs.

- Measurement and monitoring gaps: Emissions from permafrost thaw are difficult to measure accurately due to gaps in scientific monitoring and modeling. Current emissions accounting methods often focus on point sources and activity-based emissions, which do not adequately capture the diffuse and unpredictable nature of permafrost-related emissions. This lack of reliable data complicates efforts to include these emissions in national carbon inventories.

- Political will and complexity: There is a general reluctance to include permafrost emissions in NDCs because these emissions come from natural sources rather than human activities. Since permafrost thaw is driven by long-term, cumulative climate change rather than specific, immediate actions, many countries avoid the political complexities of integrating these emissions into their national targets. This hesitation is reinforced by concerns about how counting natural emissions might complicate overall climate strategies or negatively impact reported progress toward emissions reduction goals.

The absence of permafrost in NDCs reflects a broader issue within global climate governance: the voluntary and decentralized nature of NDCs often results in targets that fall short of what is necessary to meet the 1.5℃ goal. Without enforceable mechanisms or clear guidance on including natural emissions, countries lack the incentive to align their commitments with scientific realities.

Most Arctic nations recognize permafrost thaw as a threat in their broader climate policies but stop short of formalizing these emissions in their NDCs and national targets.7) For example, Canada’s climate adaptation policies8) note permafrost thaw’s impact on wildlife and infrastructure but stop short of including its emissions. Similarly, Russia recognizes the risks in its National Adaptation Plan9) but focuses its NDC on broader climate objectives, leaving permafrost emissions unaddressed. The United States, with extensive permafrost in Alaska, likewise omits any mention of permafrost thaw in its NDC. However, various reports10) and assessments11) by United States agencies have highlighted the importance of this issue. Other Arctic nations such as Norway,12) Finland,13) and Sweden14) acknowledge the importance of Arctic research and the risks of permafrost thaw in national climate policies or Arctic strategies, but the European Union’s NDC does not include permafrost emissions accounting.

Recent developments show a growing recognition of permafrost thaw risks. Canada held four Permafrost Carbon Feedback Dialogues,15) gathering Indigenous leaders and international experts to discuss the technical, policy, and ethical challenges. In the United States, the National Strategy for the Arctic Region16) outlines efforts to reduce emissions from thawing permafrost, including expanding scientific cooperation among Arctic partners. For instance, Canada and the United States issued a joint statement on advancing Arctic research and knowledge, reflecting their commitment to addressing permafrost-related challenges.17) Additionally, the Greenhouse Gas Measurement, Monitoring, and Information System18) aims to improve monitoring of permafrost emissions, which may inform future NDC updates. In the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, Norway’s recent policies and objectives include a focus on climate change and limiting permafrost thaw by preserving the vulnerable Arctic environment.19) Greenland, while not yet fully represented in Denmark’s NDC, has raised concerns about permafrost thaw in its climate planning, has joined the Paris Agreement, and is set to submit its NDC to the UNFCCC by 2030.20)

Yet, these recent efforts fall short of what is required. The exclusion of permafrost emissions from NDCs undermines the credibility of climate strategies, as it omits a significant and unpredictable source of GHGs. Failing to account for permafrost emissions not only narrows the remaining carbon budget but also jeopardizes the 1.5℃ goal. Including these emissions in NDCs is critical to recalibrating climate pathways and ensuring that global mitigation efforts align with the scale of the challenge. This issue represents a larger shortcoming in global climate commitments, where natural feedbacks like permafrost thaw remain overlooked.

Beyond permafrost, NDCs often face criticism for setting targets insufficient to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. The exclusion of natural carbon feedbacks exemplifies the broader issue of incomplete emissions accounting. Addressing this gap requires systemic reforms to raise NDC ambition and encourage countries to include emissions from both human activities and natural processes exacerbated by climate change. Including permafrost emissions in NDCs would recalibrate national targets to reflect the realities of a warming world and ensure mitigation strategies align with the scale of the challenge.

As the leading authority on climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), could play a pivotal role by providing a scientific basis for updated NDCs. For example, the IPCC’s next Assessment Report (AR7) could include specific guidance on how to incorporate emissions from permafrost thaw into NDCs. This would leverage modeling and Arctic research advances, ensuring policymakers have a clear pathway to include these emissions in their climate commitments. By creating stronger ties between NDCs and IPCC science, nations would have greater incentive–and accountability–to close information gaps, such as accurately accounting for emissions from unmanaged lands and carbon sources and sinks, including permafrost.

The Arctic Council’s Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation21) demonstrates how collaborative frameworks can enhance regional coherence, especially when nations align their efforts to shared goals. While the agreement is not a direct vehicle for climate action, it is an example of how Arctic nations could strengthen and expand existing cooperation to address permafrost thaw. By leveraging such frameworks, Arctic nations can bridge gaps in emissions accounting and bolster the credibility of their NDCs, aligning climate commitments with both regional and global needs. The key is fostering regional coherence, ensuring that climate strategies reflect the interconnected nature of Arctic ecosystems and governance structures.

Securing the Arctic’s future: key actions and collaborative solutions for permafrost thaw

Permafrost thaw represents a critical and immediate challenge with profound implications for global warming, Arctic ecosystems, and Indigenous communities. Addressing current gaps in monitoring, modeling, and policy integration is crucial to future NDC updates.

Key actions needed:

- Align Arctic NDCs with Existing Cooperation and Indigenous Knowledge: Arctic nations should align their NDCs with regional cooperative frameworks, such as the Arctic Council, while integrating Indigenous Knowledge alongside scientific research. This combined approach strengthens coherence, fosters inclusive solutions, and enhances the region’s ability to address permafrost thaw effectively.

- Enhance Permafrost Representation in Climate Goals and Reporting: Include permafrost thaw emissions in national and global climate accounting systems, and ensure unmanaged lands, including permafrost regions, are transparently reported in national climate reports. This comprehensive approach addresses critical information gaps and ensures the full recognition of natural carbon feedbacks in climate strategies.

- Strengthen Arctic Science to Support Policy and Global Engagement: Strengthen permafrost modeling and monitoring through increased research funding and advocate for including permafrost emissions in the IPCC’s AR7. Improved scientific understanding provides a foundation for integrating Arctic-specific data into national policies and global frameworks, ensuring robust and informed climate commitments.

The path forward

Immediate action is necessary to mitigate the far-reaching impacts of permafrost thaw on global climate and Arctic ecosystems. By including permafrost-related emissions in NDCs, nations can improve the accuracy of global emissions accounting, bolster climate strategies, and track progress under the Paris Agreement. This step may also drive investment in Arctic research and adaptation efforts, improve climate models, and protect infrastructure.

Arctic nations have a unique opportunity to lead in integrating permafrost emissions into global climate strategies. By aligning their NDCs with existing regional cooperation frameworks, such as those facilitated by the Arctic Council, these nations can foster international collaboration, set an example for effective climate action, and uphold their commitments to the communities most impacted by permafrost thaw. Achieving this requires robust monitoring systems and improved model capabilities. The IPCC can play a role by offering guidance on integrating emissions from unmanaged Arctic lands, such as permafrost thaw, into national GHG inventories. The Arctic Council’s Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation exemplifies how regional collaboration can enhance research coordination and data sharing. Building on its principles, Arctic nations can strengthen their collective efforts to address permafrost thaw through improved scientific research and policy coordination.

International collaboration and knowledge sharing will be indispensable in this effort. Governments, researchers, and Indigenous communities must continue working together to address the complexities of permafrost emissions, with Indigenous communities at the forefront. Many of these communities, already experiencing the direct impacts of permafrost thaw, are leading innovative strategies to mitigate and adapt to the challenges posed by a rapidly changing Arctic. We can develop more adaptive and resilient policies by fostering partnerships that prioritize inclusivity and shared responsibility. Although the task ahead is daunting, there is still time to act. Through united efforts across scientific research, policy innovation, and Indigenous Knowledge, we can confront the challenges of permafrost thaw and shape climate policy that safeguards Arctic ecosystems and future generations.

Lynn Heller is a strategic climate policy researcher with Woodwell Climate Research Center’s Permafrost Pathways project, dedicated to translating scientific findings into actionable policies that address the impacts of permafrost thaw and climate change.

References