Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Maritime Shipping (Part IV)

Icebreaker Yamal during removal of manned drifting station North Pole-36. August 2009. Photo: Pink floyd88 a

This four article series critically examines Russia’s military, energy, and shipping interests in the Arctic and how Russian policies and actions compare to the existing academic and journalistic rhetoric about the Arctic region.

The Arctic Institute Russia Arctic Strategy Series 2018

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Aimed at Conflict or Cooperation? (Part I)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Military and Security (Part II)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Energy Extraction (Part III)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Maritime Shipping (Part IV)

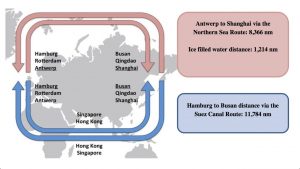

The melting Arctic ice has opened up the possibility of a new northern shipping lane, the Northern Sea Route (NSR). This maritime passage could become the fastest way of transport between major ports of East Asia and Western Europe. The NSR is the shipping route that runs along the Russian Arctic coastline from the Kara Sea to the Bering Strait. The rapidly melting sea ice has led some analysts to predict that the shorter shipping route may replace the Suez Canal Route that runs from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.1) The NSR may be commercially viable in the future since the route cuts the distance between some ports in Europe and China by approximately 40% compared to the Suez Canal Route.2)

However, the NSR is currently only safe to navigate during the summer when the straits are relatively ice-free. Even then, escort icebreaker vessels are often necessary to navigate the waters. Some scholars argue that global shipping companies may become more interested in the NSR as it becomes more viable and as piracy along the traditional Suez Canal Route remains problematic.3)

The notion that the Arctic could compete with the world’s major commercial shipping routes has also led some foreign powers, such as the US, to contest Russia’s claim over the straits.4) Since the NSR is within Russia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), the Russian authorities have great influence over the route. However, the US contests Russia’s claim and argues that the Arctic’s shipping lanes, such as the NSR, should be considered international waters and exempt from Russian regulation. The argument is that the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage (the sea route connecting the Pacific to the Atlantic via the Canadian Arctic Archipelago) are “international straits” according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.5) Nonetheless, no foreign vessel has crossed the NSR without seeking Moscow’s consent since 1965.6) The NSR is another area of debate within Arctic affairs since some writers see Russia as pursuing a unilateral policy of control and defense of the area while others argue that the opportunities for multilateral collaboration are indicative of Russia’s cooperative approach.7)

Throughout the different documents of Russian legislation regarding the Arctic, the NSR is highlighted as an important source for national and regional development. In the Development Strategy of the Russian Arctic, the NSR is designated as an international maritime navigation passage within the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation.8) Infrastructural changes are also part of Russia’s national interests regarding the route. In 2008, the Transport Strategy of the Russian Federation up to 2030 was released. According to this document, Russia aims to develop the NSR by commissioning nuclear icebreakers, improving the ports along the shipping lane and creating a ship monitoring system. Russia’s official policies regarding the NSR advocate for the development of a line of communication and the construction of search and rescue (SAR) stations by the Russian Ministry for Emergency Situations. Furthermore, it is a high priority for Russia to build an effective border control service to monitor the route and enforce regulations.9) These developments are necessary before Russia could administer the NSR as a large scale – national and international – shipping lane. They are required for authorities to be able to enforce the state’s regulation of the route and respond to distress signals.

Moscow also aims to internationalize the NSR because it can be mutually beneficial for Russia and foreign interested parties. The major trading nations of Western Europe and East Asia have expressed interest in taking advantage of the reduced transport distance and Russia hopes to benefit from its regulatory power over the route, for example by imposing duties on ships traveling through the NSR. Since 2011, over 220 vessels have traversed the NSR. These included cargo, passenger, and fishing ships from Europe, Central America, and Asia. However, the majority of ships originate or end their journeys in Russia.10) In 2016, the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) expanded its operations and sent five of its vessels to cross the NSR.11) In 2017, the Danish shipping company Maersk expressed interest in operating on the NSR. Russia’s Special Representative of Nature Protection, Environment, and Transport, Sergei Ivanov, praised this as an example of Russian-Danish cooperation “beyond the sphere of political controversies.”12) Overall, however, global interest in Arctic shipping is still quite modest. This is because of the underdeveloped maritime and land infrastructure along the NSR, the ice that covers the route during the winter season, and the associated costs shipping companies must incur. For example, there are high insurance premiums that discourage firms. But Russia is also taking steps to encourage the international usage of the route, for example by expanding its icebreaker fleet and investing in technology such as icebreaking lasers.13)

On the other hand, Russia seems to be imposing administrative barriers that could hinder international usage of the NSR. In the 2012 Federal Law on the NSR and the 2013 Ministry of Transport’s Rules of Navigation through the NSR, the conditions for passage via the Route are outlined. These documents dictate that vessels navigating the NSR are responsible for environmental pollution, tariffs, and providing proof of liability and insurance. Russia further demands that foreign ships pay for weather and ice reports, Russian pilots to guide the vessels, and using icebreaker services.14) In 2015, the Ministry of Transport proposed legislation that would prohibit companies from exporting Russian Arctic hydrocarbon resources with foreign-registered vessels.15) In 2017, the Russian legislature adopted a law that will give Russian ships the exclusive right to transport oil and gas along the NSR.16) The law is expected to be adopted in February 2018. The potential impact of this proposal is unclear, but it may require international firms interested in shipping along the NSR to hire Russian ships. These conditions are not optimal for foreign investment. Conley and Rohloff17) interpret such policies as part of a nationalistic reaction to the presence of other nations’ vessels in the Arctic.

Analysts such as Margaret Blunden18) believe that Russia fears other countries’ interference and thus takes measures to ensure state control over the NSR. A large portion of Russia’s military in the Arctic has been specifically designated to secure the NSR and Russia’s northern border. For example, the Ministry of Defense has stated that the deployment of anti-landing, anti-sabotage, and anti-aircraft units in the Arctic is an “important part of work on the integrated development of the Arctic zone along the NSR.”19) It seems that Russia is investing in a domestically profitable NSR with little regard for improving foreign parties’ prospects for shipping. Currently, most of the freight on the NSR consists of Russian hydrocarbon companies moving their resources. The NSR is unlikely to be a transport lane for other sectors or countries in the near future because of administrative barriers and Russia’s preferential treatment of domestic companies. Moreover, Egypt has expanded the Suez Canal to allow more and bigger ships to navigate the waterway.20) Altogether, this could undermine the future viability of the NSR.

Russia’s actions and policies regarding the development and defense of the NSR seem to evoke the potential for conflict over the Route’s jurisdiction and limited multilateral cooperation on commercial shipping. At the moment, defending the NSR is a high priority for Russia. The construction of military-related infrastructure and the deployment of armed forces explicitly to protect the NSR demonstrate that Russia is cautious of potential conflict. A 2016 study by the Copenhagen Business School’s Maritime Division found that the NSR will become economically viable only after 2035. This is mostly because the route is covered by ice the majority of the year and the associated fees for transport are too high.21) This suggests that potential conflict over the NSR is probably yet to emerge. Overall, Russia’s attitude towards the NSR is concurrently concerned with controlling its borders and encouraging international firms to partake in shipping. However, President Putin’s recent proposal to exclude international ships from transporting Russian natural resources along the NSR may undermine any potential forms of cooperation in NSR shipping.22)

Conclusions

Russia’s policies and actions in the areas of security, energy and shipping demonstrate that Russia’s Arctic policy is multifaceted and cannot be solely reduced to its military or economic development component. Especially, the nature of Russia’s ambitions is more nuanced than just an orientation towards conflict or cooperation. There exists a duality of these elements in Russia’s Arctic policies. On the one hand, Moscow is prepared to confront any emerging threats to its Arctic territory, maritime transport ventures, and energy projects. Russia is establishing defense capabilities during a period of heightened tensions with its neighboring countries. Moreover, state legislation that gives preferential treatment to domestic firms suggests that Russia is prepared to unilaterally control and develop its portion of the Arctic.

On the other hand, there is evidence that Russia is open to cooperation with foreign partners. Russia’s latest Arctic strategy is not primarily concerned with deterrence or military parity. Military and civilian security actions are concerned with supporting the national interests outlined in official strategy papers. In anticipation of greater interest in energy extraction and increased international shipping traffic, Russia has sought to modernize its military and civilian units and infrastructures. Russia’s security programs are pragmatic as they aim to maintain control over the region while simultaneously cooperating with other Arctic states’ via military drills and SAR collaborations, often for civilian purposes. There is ample evidence of Russia engaging in cooperative projects in energy extraction.

The majority of academics and mainstream journalists who have commented on Arctic affairs have either reduced Russia’s Arctic strategy to its security dimension or declared that Russia is solely concerned with economic development. Instead, Russia’s Arctic policy must be simultaneously viewed through the perspectives of conflict and cooperation. The conflict narrative, mostly developed after the 2007 North Pole expedition, led writers to conclude that Russia was staking its claim to disputed territory in the Arctic.23)24) Although no legal implications emerged from the flag planting, the event is still constantly discussed in papers on Arctic affairs25)26) Russia’s realist ambitions were also expected by many in the West after Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, a few months before the Arctic expedition. The cooperation narrative developed out of responses to writers who expressed such warnings and is thus slightly more nuanced. Nonetheless, some writers disregard Russia’s actions and statements that are explicitly aimed to counter other states’ actions and hinder international cooperation.

There is a tendency amongst Russian policymakers to simultaneously pursue international cooperation and to project power by fostering security practices. To not consider the multifaceted nature of the Russian Arctic policy is dangerous and could lead to inadequate policies from other countries that may jeopardize the current stability and peace in the Arctic. The view from Russia is that NATO member states use alleged Russian aggression in the Arctic as a justification for their own military ambitions.27) Policymakers’ emphasis on Russia’s military build-up could then lead to a security dilemma where deterrence could hypothetically lead to engagement.

The current trajectory of Russia’s Arctic policy gives some hope for future cooperation in economic ventures. Russia will chair the Arctic Council between 2021 and 2023 and will therefore be responsible for leading intergovernmental efforts to address issues of development, shipping, extraction, and environmental protection. Although the Arctic Council is not a forum for traditional security matters, it can be argued that cooperation in non-military issues lessens the chances of confrontation. Building economic alliances and working together on issues such as environmental protection may prevent an escalation to conflict since it becomes possible for countries to solve problems through peaceful means. At the 2017 International Arctic Forum in Arkhangelsk, President Putin28) stressed that Russia is open to constructive cooperation. He invited his foreign colleagues to engage in economic projects in the Russian Arctic. Hopefully, the same level of diplomacy and peace can apply to the security sphere as well.

This series of articles has examined how Russia seeks to secure its Arctic territories, enhance circumpolar security, extract Arctic energy, expand NSR shipping, and encourage multilateral cooperation in economic ventures. Throughout the official policies regarding the Arctic, Russia’s stance has evolved from an abrasive rhetoric that seeks parity with neighboring states to a posture that encourages cooperation in many fields. In terms of its actions, Russia has exercised measures that can be classified as conducive to both defensive realism and pragmatic cooperation. All in all, it can be argued that Russia’s Arctic policy is concurrently focused on conflict and cooperation.

References