Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Energy Extraction (Part III)

Arctic offshore oil platform “Prirazlomnaya” in the Pechora Sea, south of Novaya Zemlya, Russia. Photo: Gazprom.

This four article series critically examines Russia’s military, energy, and shipping interests in the Arctic and how Russian policies and actions compare to the existing academic and journalistic rhetoric about the Arctic region.

The Arctic Institute Russia Arctic Strategy Series 2018

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Aimed at Conflict or Cooperation? (Part I)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Military and Security (Part II)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Energy Extraction (Part III)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Maritime Shipping (Part IV)

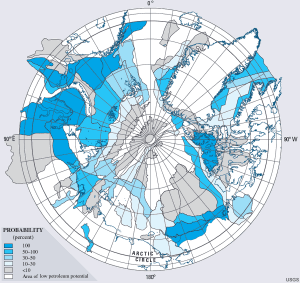

As the rate at which sea ice is melting in the Arctic accelerates, analysts have predicted unprecedented access to vast deposits of undiscovered oil, natural gas, and other natural resources. In 2008, the US Geological Survey estimated that the Arctic may contain 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil and up to 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas resources.1) Two thirds of Russia’s oil and gas is expected in Russia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) off its Arctic coasts.2) Such statistics are often used to back up the academic and journalistic hype over an impending competition for the Arctic’s natural resources, even though estimates show that only a small amount of undiscovered resources are in disputed territories.3)

Competition for Arctic Resources

Given the rising global demand for oil,4) the Arctic’s natural resources have found their way into the debate on Arctic affairs. The mostly unexplored sources of hydrocarbon have propagated a debate on whether the Arctic will be an area of conflict between competing Arctic countries or a zone of cooperation based on mutual interests. Marlene Laruelle5) characterizes the two sides of this debate as “resource nationalism versus patterns of cooperation.”

Since Putin’s first presidency in 2000, Russia has undergone a process of re-nationalizing its oil and gas companies.6) As a result, some of the largest Russian oil and gas companies, such as Rosneft and Gazprom, are under the complete or majority control of Russian state authorities. There is a common argument among writers such as Shane C. Tayloe7) and Scott Borgerson8) that Russia seeks to reap the benefits in the Arctic to achieve power parity with the United States and ultimately regain its great power status. They also believe that the possible hydrocarbon deposits in the Arctic will lead to competition and an inevitable military clash for resources.

Among the five littoral states, Russia possesses more than half of all the Arctic’s estimated oil and gas resources.9) In other words, Russia is in control of the majority of the Arctic’s hydrocarbons because they fall within their maritime boundaries. Further, this is supported by Russia’s history of extensive production and exploration in the Far North. The US Geological Survey’s probability map of Arctic oil and gas (see map below) shows that most hydrocarbons (indicated by the darker colored territories) are located far from the disputed seabed areas around the North Pole and the Lomonosov Ridge.10) The conclusion is that there is little incentive for Russia to aggressively seize the North Pole or other nations’ territories for their resources because of their own vast resource base.

Arctic Energy Cooperation

International cooperation is becoming increasingly desirable since unilaterally exploring and developing the Arctic is expensive and complicated. The technological and logistical challenges of extraction in the remote and climatically harsh Arctic have led Russia to seek business and technological cooperation with American and European companies. In the aftermath of the Ukraine crisis, many Western oil companies found it difficult to work with Russian companies to explore the Russian Arctic. Western sanctions and Russian counter-sanctions prevented Western firms from participating in large-scale exploration and extractive efforts. Initially, the sanctions hindered partnerships in the oil industry, but the US (without the EU) has more recently also targeted the Russian gas industry.11)

Failed Cooperation

One planned energy project involved American energy giant ExxonMobil’s plan to partner with Rosneft to develop oil and gas fields in Russia and North America. In 2012, Rex Tillerson and Igor Sechin, the then chief executive officers of ExxonMobil and Rosneft respectively, signed a deal that was worth $500 billion. The deal would have granted ExxonMobil access to the Russian Arctic with exemption from export duties and property tax. It would have been one of the biggest energy extraction projects in history before the sanctions put the deal to a halt.12) After Rex Tillerson was appointed Secretary of State, there was speculation that the new US administration would reinstate the deal or reduce sanctions. However, in April 2017 the US Treasury decided to not grant a waiver to ExxonMobil after they requested permission to drill in the Russian Arctic.13) The attempted deal was nonetheless an indication of Russia’s openness to cooperating with other states in energy extraction.

Successful Cooperation with Western Europe

There are currently many instances of partnerships moving forward. Since the majority of Arctic hydrocarbons are expected to be in Russia’s EEZ, foreign companies are interested in exploring the Russian Arctic in spite of the sanctions. In 2016, British Petroleum formalized a joint venture with Rosneft to assess the prospects of extraction in Western Siberia and the Yenesey-Khatanga basin.14) In 2017, BP and Rosneft struck another joint venture to extract gas in the Yamal-Nenets region.15) Russia and Norway have recently agreed to share seismic data on the Barents Sea region to boost the mutual exploration for gas and oil.16)

Russia looking East

Russian corporations such as Novatek and Rosneft have also been especially successful at cooperating with energy companies from Asia. Russian companies have signed agreements with the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and the China Development Bank to fund the Yamal LNG project after Western companies withdrew their support and funding in line with the sanctions in response to the Crimea and Ukraine crises.17) Although China and Russia have been able to agree on a certain degree of cooperation, there are still challenges that prevent a full-fledged partnership. Russia’s reliance on extractive technology from the West and the fear of “China’s rise” are such obstacles. Although Russia shares strategic interests with its neighboring countries and other interested parties, low oil prices and high production costs make Arctic oil production less profitable.18) Nonetheless, the overall trend is that the Russian state and Russian firms have been effective at cooperating with foreign companies in energy extraction and this has not been conflictive.

Official Energy Policy

Russia’s official commitments to the Arctic’s economic development can be found in the 2013 Development Strategy of the Russian Arctic. One of Russia’s strategic priorities is to expand Russia’s resource base in the Arctic region so that it can satisfy Russia’s need for “hydrocarbon resources, water bio-resources and other types of strategic raw materials.”19) Alexander Pelyasov20) remarks that the most recent Development Strategy mentions economic priorities more often than it discusses defense priorities. The document is noticeably more open to international cooperation in the interest of developing the region through joint projects. The Arctic is regarded as an enormous source of natural resources. Considering the significance of the energy industry to the Russian economy, exploiting the Arctic is considered an essential mechanism for Russia’s social and economic development. Highlighting this objective, former President Medvedev said that Russia’s “first and main task is to turn the Arctic into a resource base for Russia in the twenty-first century.”21)

Another important document that presents Russia’s official stance is the Energy Strategy for Russia up to 2030.22) It states that Russia aims to “increase geological exploration, private investments, and state participation in the development of new territories and waters.” These are general aims but we learn from the document that the Russian state hopes to enhance Russian energy companies’ positions abroad and provide an environment for efficient international cooperation for sophisticated projects in the Arctic. The regions of Eastern Siberia, the Yamal Peninsula, and the continental shelf of the Arctic seas are highlighted as they are relatively under-explored in comparison to other Russian regions. Lastly, one of the main strategic priorities of Russia is to develop the hydrocarbon potential of the Arctic continental shelf and the northern territories of Russia. The move towards the Arctic is intended to compensate for the decreases in oil and gas production in Western Siberia.

In 2012, the State Program for the Development of the Continental Shelf in the Period up to 2030 established the Arctic continental shelf as a territory for exploitation solely by state companies, namely Rosneft and Gazprom. With the support of the Russian state and an unchallenged control over the Russian Arctic, Russia’s state-owned oil and gas companies enjoy outstanding exploration and exploitation privileges. However, former Minister of Natural Resources Yuri Trutnev has stated that the preference given to national oil companies over international companies actually hinders development of the Arctic shelf.23) Russia would benefit from improving its investment climate and making it easier for foreign companies to cooperate with Russian firms. Foreign firms are officially allowed to enter into partnerships with Russian corporations but foreign holdings cannot exceed 50% according to the 2008 Foreign Investment on Strategic Sectors legislation.24) This legal measure is an example of what Laruelle25) calls “resource nationalism.”

Nationalism in Energy Policy

Writers who subscribe to the concept of “resource nationalism” tend to view Russia’s development of natural resources through the perspective of nationalism. Moreover, analysts argue that Russian actions regarding natural resources are based on what they call “harder security or military considerations.” For example, Michael L. Roi26) argues that Russia is using the earnings from its energy industry to rebuild its military capabilities. The narrative points to Russia’s historical use of natural gas policies to influence its neighbors and the close ties between the Kremlin and the Russian energy sector. Katarzyna Zysk27) argues that there is interdependence between the development of the Russian oil industry and Russian military power in the High North. For instance, there are influential Russian officials with great authority in Arctic and defense affairs. The head of Russia’s Arctic Commission, Dmitry Rogozin, is also the Deputy Prime Minister of the Russian defense and space industries, as well as Russia’s former ambassador to NATO. Rogozin is a controversial politician; he is sometimes called the “architect of Russia’s Crimea strategy.” He is also often regarded as a leading figure in Russia’s militarization of the Arctic. Heading the Arctic Commission means he is responsible for the economic development and security of Russia’s Arctic regions.28) Rogozin’s role could suggest that defense industries play a pronounced role in Russia’s extraction affairs.

Conclusions

In the energy domain, Russia’s Arctic policy concurrently involves elements of resource nationalism, competition, and cooperation. Russia is motivated to work independently from Western companies after the Ukraine crisis and has therefore turned to interested partners in Asia. The reinvestment into the Russian Arctic by some Western firms shows though that political tensions do not completely obstruct private sector collaborations. The concept of “resource nationalism” does not necessarily increase the chance of a military confrontation but it contributes to political tensions. As with other spheres of the Russian Arctic policy, the varied nature of Russia’s energy practices demonstrates that conflict and cooperation are not mutually exclusive.

I would like to thank my colleagues from The Arctic Institute Ryan Uljua, Dr Kathrin Stephen, Greg Sharp, as well as Dr Felix Ciută, and my family for their support and guidance throughout this project.

References