Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Military and Security (Part II)

Reconnaissance unit members of the Northern Fleet’s Arctic mechanized infantry brigade conduct military exercises and learn how to ride a dog sled. Photo: Lev Fedossev

This four article series critically examines Russia’s military, energy, and shipping interests in the Arctic and how Russian policies and actions compare to the existing academic and journalistic rhetoric about the Arctic region.

The Arctic Institute Russia Arctic Strategy Series 2018

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Aimed at Conflict or Cooperation? (Part I)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Military and Security (Part II)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Energy Extraction (Part III)

- Russia’s Arctic Strategy: Maritime Shipping (Part IV)

Russia’s military policy in the Arctic is arguably the most controversial sphere of the Russian Arctic strategy. It is the most discussed theme when analysts characterize Russia’s Arctic strategy as motivated either by conflict or cooperation. In recent years, Russia has increased Arctic military drills, opened or reopened military bases, constructed icebreakers, and established advanced radar stations to enhance its control of the region. Such actions have led some journalists to proclaim that President Putin has opened an Arctic Front in a New Cold War.1) Sensationalist journalists argue that any Russian military activity in the region is in preparation for war or for conquering the Arctic.2) Leading policymakers have also contributed to the hype around Arctic affairs. US Secretary of Defense James Mattis declared that Russia is taking “aggressive steps” to increase its presence in the Arctic.3)

The build-up of Russian military assets in the Arctic leads many to believe that a war is in the making. However, despite this alarmist rhetoric, there is evidence that the Russian presence in the Arctic is equally motivated by the potential gains that can be achieved by circumpolar cooperation. Based on recent policies and actions in the Arctic, it can be argued that Russia is concurrently motivated by the threat of conflict and opportunities for circumpolar cooperation.

Russia’s Official Arctic Policy

It is necessary to assess the formal approach of the Russian state as laid out in government statements and strategy documents. The Russian Arctic policy is complicated since it is spread across different official documents, each put forward by various bodies of the Russian state machinery. There have also been frequent revisions of existing doctrines since the early 2000s. Shortly after Vladimir Putin’s rise to presidency in 2000, the Basics of State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic Region was endorsed.4) This policy declared that all activities in the Arctic should be tied to the interests of “defense and security to the maximum degree.” For example, the Russian military must prioritize the reliable functioning of sea-based nuclear forces for the purpose of deterring threats of aggression against Russia and her allies. As such, this early strategy concentrated much more on military issues than the documents that followed.

In September 2008, the document on Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic for the Period Until 2020 and Beyond was approved by then President Dmitry Medvedev.5) This is perhaps the most noteworthy and discussed Russian Arctic strategy document since it followed shortly after the 2007 North Pole expedition. The Foundations of the State Policy serves as a doctrinal agenda for the Russian state’s goals and interests in the Arctic. The document also lays out a plan for the implementation of the State Policy. Further, the Foundations of the State Policy proposes to maintain the Arctic as a region of peaceful cooperation. Ensuring national security and protecting the northern border requires a persistent build-up and modernization of military capabilities. Thus, Russia aims to create and maintain armed forces able to operate in the Arctic. Alyson J.K. Bailes and Lassi Heininen6) observe that the State Policy simultaneously considers the Arctic as both “a zone of peace and cooperation” and as “a sphere of military security.” In comparison to the previous 2001 State Policy, the 2008 strategy is also more open to security cooperation rather than anticipating a military clash. This tells us that the Russian military policy in the Arctic is based on achieving peace through security.

In February 2013, Russia’s official Arctic strategy was expanded when President Putin approved the Development Strategy of the Russian Arctic and the Provision of National Security for the Period Until 2020.7) The new document is essentially an expansion of the 2008 strategy since it provides a more comprehensive description of Russia’s objectives, priorities, and means of implementation. Regarding military and security priorities, the defense of Russia’s national interests remains significant to the Russian Arctic policy. For example, one priority is the establishment of an integrated security system for the protection of territory, population, and critical facilities. National security in the Arctic requires an advanced naval, air force and army presence in the Arctic. Further aims include developing the Russian icebreaker fleet, modernizing the air service and airport network, and establishing modern information and telecommunication infrastructure.

Foreign Policy in the Arctic

The 2013 Development Strategy of the Russian Arctic does not completely encompass Russia’s Arctic military program since it concentrates on the Russian Arctic (i.e. Russia’s undisputed territories and exclusive economic zone) rather than the whole Arctic region. The greater principles of Russia’s foreign policy and relations with other states in the Arctic can be found in the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, the most recent version of which was approved by President Putin in November 2016. This policy framework contains the idea that Russia has reemerged as a key player in international politics and that Russian foreign policy should aim to “consolidate Russia’s position as a center of influence.” This ambition lends some validation to the rhetoric that Russia’s policy in the Arctic is based on restoring its great power status. In the chapter on Regional Foreign Policy Priorities, the Arctic is highlighted for its strategic importance. In reference to the Arctic, Russia hopes to pursue policies that “promote peace, stability and constructive international cooperation.” Russia also proclaims that the state will “be firm in countering any attempts to introduce elements of political or military confrontation in the Arctic.”8)

National Security Policy

Russia’s National Security Strategy (NSS) up to 2020 from May 2009 is another important document to consider when analyzing the state’s military policy in the Arctic.9) The NSS is a useful indicator for how Moscow formally addresses domestic and foreign security issues. It encompasses Russian security policy by defining security threats and suggesting measures to secure Russia against those threats. Economic development and energy security have prominent positions in the strategy. These factors are important given that Russia consistently considers the Arctic as a strategic resource base. The NSS also suggests the formation of a military force for the Arctic. Bailes and Heininen10) notice how the NSS expands upon the traditional concept of security to include human and environmental security. It is important to note that the Russian word for security (bezopasnost’) is also the word for safety. In this sense, security activities in the Arctic are concerned with protecting Russia from traditional military threats and non-traditional dangers such as environmental damage. As in other contemporary Russian doctrines, the state’s commitment to working within international law and cooperating through multilateral channels is stressed. The most recent NSS was approved in December 2015. In the chapter on strategic stability and partnership, the “development of equal and mutually beneficial international cooperation in the Arctic” is prioritized.11)

Comparing the Policies

Both the Development Strategy of the Russian Arctic and the NSS contain a much less abrasive rhetoric compared to the documents’ earlier versions. The newer Arctic strategy papers focus on preventing smuggling, terrorism, and illegal immigration instead of balancing military power with NATO. These priorities suggest that Russia’s security aims in the Arctic have to do with safeguarding the Arctic as a strategic resource base. The 2008 and 2013 editions of the Development Strategy do not mention the military activities of other nations or frame Russia’s security policy in competition to NATO. Over time, the strategy papers have fewer allusions to the role of traditional military security.

Nonetheless, Russia’s Ministry of Defense has consistently called for the development of Russian military facilities in the Arctic to meet emerging dangers. According to Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu, a wide range of threats to Russia’s national security – which often remain rather vague – are developing in the Arctic.12)

In the 2014 Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation, the Arctic is mentioned as a region where the Armed Forces must protect Russia’s national interests even during peacetime. However, the document calls for a general military restoration rather than an increase of offensive capabilities.13) In general, the government-approved documents seem to have moved from an assertive tone that highlights Russia’s rivalry with NATO to a less abrasive tone based on securing economic development. Even so, both attitudes are still present in Russian policy-making since they are not mutually exclusive.

Military Activity in the Arctic

Guided by the official policies, Russia has taken many measures towards realizing its security ambitions in the Arctic. Accordingly, Russia’s military modernization and build-up has not gone unnoticed by the global community. Russian military activity in the Arctic can be characterized by a continuous focus on evolving and expanding military capability across different branches and throughout the Russian Arctic. Since the 2007 North Pole expedition, Russia has aimed to maintain a comprehensive sea, air, and land presence in the Arctic to fulfil their aims set out in the various security doctrines.

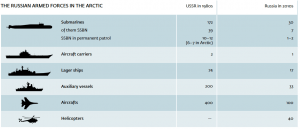

In August 2007, Russia resumed strategic bomber and Northern Fleet patrols in its Arctic waters for the first time since the end of the Cold War. Russia has also invested significantly in its naval capacity in the Arctic. The Northern Fleet is arguably the most important asset of the Russian military in the Arctic. It is the most powerful of the four Russian fleets with the greatest number of icebreakers and submarines. The Northern Fleet’s sea-based nuclear deterrence capability makes it a fundamental part of Russia’s military. Russia has expanded naval patrols near Norwegian and Danish territories, increased the operational radius of the Fleet’s submarines, and commenced below-ice training for submarines.14)

Russia’s long-range bomber and naval patrols have been controversial in the West but they are far below the level they were during the Cold War. In numerical terms, the Russian military presence in the Arctic is much smaller than the Soviet presence was during the 1980s.15) It can be argued that Russia does not seek to return to the hostilities of the Cold War but rather to protect its large territory by maintaining a modern military presence in the Arctic. Nonetheless, this suggests that Russia is prepared for conflict.

Further military activities in the Arctic have included extensive investments into missile defense systems. The Russian military is developing its air defense shield and building military infrastructure across island bases in the Russian Arctic. The Ministry of Defense has announced that they aim to put more than 100 military facilities into operation in 2017. Since 2015, Russia has constructed six new bases that have included new airfields, ports and army bases.16) These actions show that Russian security policy in the Arctic is more than simply upgrading existing military infrastructure.

In addition, traditional armed forces are becoming involved in the Arctic to learn military tactics for Arctic warfare. Although Russia’s military activities in the Arctic are mostly aerial and naval, there are garrisons of Russian ground troops and security services throughout the Russian Arctic. Commander of the Russian Ground Forces Alexander Postnikov has called the establishment of an Arctic brigade close to Norway’s border an attempt to “balance the situation” since the US and Canada would maintain similar brigades in the Arctic (although Canada has no comparable presence in its Arctic region).17) The Russian Ministry of Defense has declared the many Russian snap military drills in the Arctic as direct responses to NATO military activities in Scandinavia such as the Arctic Challenge Exercise.18) These activities support the argument that Russia’s Arctic endeavors are a response to possible conflict. Such modernization programs and the expansion of military infrastructure have potential offensive capabilities.

Security Cooperation

Military drills and the build-up of military facilities do not imply that Russia is preparing for war with the other Arctic states. Instead, Russia’s renewed security activism should be interpreted as a desire to maintain its capabilities rather than develop new offensive abilities. It is crucial to acknowledge that many of Russia’s military-related activities are pragmatic and cooperative in nature. The alarmist rhetoric has produced assessments such as Senator Dan Sullivan’s (R-Alaska) map of Russia’s Arctic build-up. The map below was used in 2017 to call on the US Senate to create an Arctic Strategy to counter Russia’s aggression. It shows the large amount of infrastructure Russia has erected for defense, but it puts military airfields and the more numerous search and rescue (SAR) stations into the same category. As a result, Russia’s actions in the Arctic are inaccurately seen as belligerent.19)

Civilian Security Cooperation

Russia’s search and rescue (SAR) centers, radar surveillance systems, and joint military exercises have also been instruments of cooperation in the fields of security and safety. As the Arctic becomes more suitable for economic development, Russia is improving its radar surveillance and communication over the Arctic. Throughout the Russian Arctic, the Russian military is developing long-range radar systems and drone bases to enhance control and surveillance over Russia’s oil reserves and maritime shipping.20) Critics like Senator Sullivan may interpret such facilities’ construction as geared towards military reconnaissance, but they are actually essential for peacetime SAR operations. SAR stations are necessary to assist foreign and domestic resource extraction, shipping and other economic developments because of the region’s harsh climate, remoteness and unreliable communication systems.

SAR operations have also been an important part of circumpolar cooperation. The Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum for the discussion and resolution of Arctic issues, has been an important institution for Arctic peace and cooperation, including on SAR. Two legally binding agreements negotiated under the auspices of the Council have mandated international cooperation on SAR operations and oil pollution preparedness and response.21) The 2011 agreement on SAR operations commits all parties to respond to signals of distress within their respective areas. Each nation is responsible for their territory in the Arctic. The coast guards of the eight Arctic states have also agreed on establishing the Arctic Coast Guard Forum (ACGF) in 2015. The ACGF was formed for the Arctic Council states’ coast guards to coordinate emergency response operations in the northern seas.22) As the American and Russian coast guards are part of the US Armed Forces and Russian Federal Security Service respectively, the ACGF is indicative of cooperation between military branches of the Arctic nations. These actions are consistent with the “strategic stability and partnership” goals laid out in Russia’s official policies.

Joint Military Drills with other States

Russia has also carried out many joint military exercises with NATO member states. For example, Russia and Norway have conducted many naval drills in the Barents Sea. Between 2010 and 2013, they carried out the annual joint naval exercise Pomor. The Norwegian Coast Guard and the Russian Northern Fleet have jointly held an annual Barents drill since 2015. Outside of the Arctic, Russia also conducted the annual FRUKUS exercise with France, the UK and the US between 2003 and 2013. Following the Ukraine crisis in 2014, such multilateral military exercises between Russia and NATO member states were put on hold. However, joint coast guard exercises involving SAR operations and oil spill response training continued.23) In general, it can be argued that many of Russia’s military and civilian operations are pragmatic in nature and have allowed a certain degree of cooperation between the Arctic states.

So far, there is no general pattern of assertive Russian militarization in the Arctic. Instead, most of the military and civilian units in the region seek to patrol, react to unconventional challenges, and protect Russia’s borders. However, some journalists, academics, and pundits perpetuate the idea that the Arctic is becoming a zone of rising conflict and that nations must prepare for war with Russia.24) For example, alarmist analysts still contrast contemporary Russian military activity to the 1990s when Russia was absent from the Arctic. In the aftermath of the Cold War, the Arctic was not a military priority for the new Russian Federation since the Soviet Union’s collapse precluded the state’s ability to keep an advanced military presence in the Far North. Compared to the Soviet era, current Russian military measures are marginal and oriented towards domestic audiences. Moreover, Russia’s current modernization programs aim to upgrade military infrastructure left over from the Soviet period. Then Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs Jonas Gahr Støre25) characterized Russia’s activities as “a return to a more normal level of activity for a major power with legitimate interests in the region.” More recently in 2016, Julia Gourley, the then Senior Arctic Official of the US, said that there has been “no evidence of aggressive intent by Russia” in the Arctic.26)

Conclusions

Political tensions between Russia and NATO member states in other parts of the world have exacerbated uncertainty. The Ukraine crisis has particularly impacted Arctic cooperation and raised concerns regarding the emergence of a new Cold War. Previous periods of tensions between the West and Russia, such as the 2008 War in Georgia, have arguably not had such an impact on Arctic affairs as the war in Ukraine.27) In the aftermath of the Ukraine crisis, the US and other NATO governments have affirmed their commitment to meeting Russian militarism around the world, including in the Arctic. For example, the current US Secretary of Defense Mattis’ characterization of Russia’s Arctic actions as aggressive are consistent with Senator Sullivan’s push for a US Arctic Strategy.28) Russian official policies and statements from the Ministry of Defense stress the importance of national security and are the basis for much of Russia’s security activism in the region. On the other hand, Russian foreign policy and national security papers call for building partnerships with foreign states. Russia seeks to simultaneously collaborate in civilian and security dimensions, modernize their defense forces, and secure their large territory from potential threats. As a result, there are both elements of conflict and cooperation in Russia’s Arctic security affairs. Ultimately, it comes down to the perspective through which one chooses to perceive Russian Arctic policy.

I would like to thank my colleagues from The Arctic Institute Ryan Uljua, Dr Kathrin Stephen, Greg Sharp, as well as Dr Felix Ciută, and my family for their support and guidance throughout this project.

References