The Role of International Law in Controlling Black Carbon Pollution in the Arctic

Photo Credit: Kris Krüg, Flickr

The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the global average, making climate change’s polar effects more intense than anywhere else in the world. Some scientific projections show that the North Pole will have completely ice free summers by 2050. While a jarring image to imagine, climate change is transformative as its consequences reach much further than receding sea ice. The Arctic Institute’s Beyond the Melt project explores the hidden side of Arctic climate change. Delving into issues as far ranging as persistent organic pollutants, methane energy sources, and warm-weather diseases, our research team uncovers, analyses, and shares the unexpected challenges and opportunities of a rapidly changing Arctic.

Black carbon has been high on the political agenda of the Arctic Council, and for good reasons. It is believed that immediate reductions of black carbon (BC) emissions might slow the Arctic warming in the next decades and ‘buy’ the international community some time to come up with more effective CO2 mitigation measures. This article will consider the ways in which BC emissions are regulated at the international level and demonstrate the limited relevance of the binding or non-binding nature of international norms in this respect. It will further argue that the diversity of sources of BC across the Arctic States calls for the same diversity in regulation. It also suggests that the BC and Methane Framework1) is a step towards an improved regulatory and cooperative function of the Council.

BC, better known as soot, is a particulate matter formed through the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and biomass. It warms the Earth by absorbing the heat in the atmosphere. In the Arctic the effects of BC are especially noticeable since it darkens snow and ice thus reducing their albedo (ability to reflect sunlight). Melting snow and ice expose dark ocean or land that have a much lower albedo and absorb even more sunlight thus creating a positive feedback loop.

In the Arctic, main BC sources include open burning, diesel vehicles, electricity generation, and gas flaring.2) Whereas BC emissions from shipping have not been identified as a primary source yet, they are expected to increase with a high-growth scenario for the Arctic shipping ‘nearly fivefold by 2030 and over 18-fold by 2050.’3) The recent open letter from 15 environmental NGOs to the chair of Senior Arctic Officials group calls for a ban on heavy fuel oil, a primary source of BC from ships.

BC is a short-lived climate forcer, meaning it lives in the atmosphere for a few days or weeks. Therefore, while the efforts to reduce BC cannot replace long-term efforts to mitigate CO2 emissions, immediate reductions in BC output could lower the rate of Arctic warming over the next few decades. In addition to its warming effects, BC has negative effects on human health causing respiratory diseases that sometimes lead to premature deaths.4)

How is the Arctic Black Carbon regulated?

The distinctness of the BC problem from the regulatory point of view is that it belongs to both air pollution and climate change. On the international level, BC as an air pollutant is covered by the Gothenburg Protocol under the Convention on Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP). As a climate forcer, it is being addressed by the Arctic Council non-binding BC and Methane Framework. September 2015 was a deadline for the first national reports under this Framework. As of March 2016 all of the Arctic Council States, 8 Observer States, and the EU have submitted their reports to the Council. These national submissions are not just the usual emissions data sheets, but rather are comprehensive reports containing mitigation measures, Arctic-relevant projects descriptions, cross-border cooperation examples, and best practices.

CLRTAP

The CLRTAP was adopted under the auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Under its framework, the Gothenburg Protocol was adopted with a view to define binding quantitative reduction targets for various pollutants. In 2012 it was amended to include PM2.5, or ‘particulate matter’ of which BC is a component. Despite the European focus the CLRTAP has been actively engaged with by the North American UNECE members: Canada and the US.

While all the Arctic States are parties to the CLRTAP, Canada, Russia, and Iceland have not yet ratified the protocol. Even for the states, the protocol provides flexibility mechanisms with regards to the amendments. The amendments are approved by consensus, and even after the adoption they only enter into force for the Parties that have explicitly accepted them (art. 13(bis) 3). This mechanism has allowed the US to set an indicative target for PM2.5 reduction, rather than accepting any binding reduction commitments.

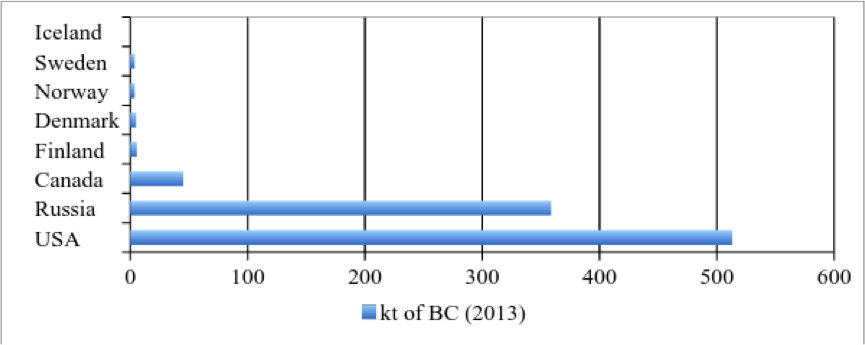

Thus, out of 8 Arctic States only 4 Nordic countries have agreed to the binding PM2.5 reduction goals. With Canada, Russia, and the US out of the picture, the biggest polluters in the Arctic are either left outside the jurisdiction of the Protocol or do not have binding reduction obligations under it. It is interesting to note that in the Nordic States the work on reductions in BC and methane was begun prior to these commitments.5) In fact, it was Norway that proposed the amendments to the Protocol in the first place. Despite that, all the Arctic States submitted their BC emission data to the CLRTAP in 2015.

Arctic Council Framework

The Arctic Council first acknowledged short-lived climate forcers in 2009 during a Ministerial Meeting in Tromsø by creating a Task Force on SLCFs and assigning it the identification of ‘existing and new measures to reduce emissions of these forcers and recommend further immediate actions that can be taken.’ Later in the year the task was refined to focus on BC due to its ‘unique role’6)) in the Arctic. After publishing two reports, the task force was restructured into the Task Force for Action on BC and Methane (TFABCM).

In 2013 during a Ministerial Meeting in Kiruna the Council recognised that the reduction in BC emissions ‘could slow Arctic and global climate change and have positive effects on health’7) and made national BC emissions inventories ‘a matter of priority’. The main normative deliverable produced following the work of the Task Force is the Framework for Enhanced Action to Reduce Black Carbon and Methane Emissions. It was decided that the document would avoid setting any quantitative targets until 2017, even though just two months prior to this decision during the 5th meeting of the TFABCM ‘most [participants] indicated a preference for a quantitative vision.’8)

Instead, the framework was intended to ‘send a strong political signal in the form of an ambitious, politically aspirational collective vision.’ The framework has been seen as a ‘breakthrough’ since it was the ‘first time that the council’s eight member states have acted to reduce human-induced climate change.’9)

The decision not to set a common BC emission reduction target could be justified by a number of factors. First, the scientific work on the BC emission sources and detection is still ongoing. Some large emitters, such as Russia, did not have proper reporting inventories.10) Second, setting quantitative targets just for the Arctic states would not solve the problem, as a large amount of BC comes from Western Europe and South-East Asia.

The first outcomes of the framework were released in September 2015 when some of the Arctic Council Members and a number of Observers submitted their reports. It is worth noting that while Denmark did not submit a report to the Arctic Council, it did send the data on BC emissions to the CLRTAP. The framework’s scope does not end at reporting: the compilation of the national submissions is then being reviewed by the Expert Group, which will in turn issue conclusions and specific recommendations that will serve as a guide for further action.

Over the years the Arctic Council has been praised for its capacity to conduct large-scale scientific assessments and for its monitoring activities in the Arctic.11) However, its regulatory attempts have not been as successful. It was not only due to the Council’s inability to take binding decisions, but more due to the lack of follow-up in its previous non-binding instruments.12) The BC and Methane Framework allows the Council to use its scientific capacity to evaluate policy actions and effects, which might prove more effective than simply issuing guidelines.

What do National Submissions Show?

The national submissions under the Arctic Council’s framework represent a remarkable set of data. First, they are rather varied: while the US submission with its informative data and impressive graphics is truly worthy of a Chairman-State, Iceland’s submission is a 3 pages long and states simply that their BC inventory is still in the making. Perhaps fitting given how much each country emits in real terms.

Secondly, BC emissions have been generally in decline over the last decade. That being said, BC has never been a direct target of legislation. It is largely the reforms in transportation pollution laws that prompted the decline.13)) States also quote industry regulation as prompting that decline.14)

Thirdly, eight Arctic Council Observers and the EU submitted their national reports. While not as elaborate as those produced by the Arctic States, they do represent a step forward towards a more inclusive role of Observers in the Council. Given that Asian states account for 43% of BC burdens in the Arctic,15) involving them in this process holds significant potential. However, as Rachael Johnstone points out, negotiating a binding treaty with them would take the matter out of the Council’s control and would be ‘more difficult and time-consuming.’16)

Finally, sources of BC largely differ across the Arctic States. In Russia, for example, almost half of BC emissions come from flaring and venting practices. Russia flares the second largest amount of associated petroleum gas in the world (after Nigeria) and would benefit from improving its relevant laws and working closely with the oil and gas sector in their implementation.17) In Canada and the US – the majority of BC originates from mobile sources and diesel-powered transport; in Nordic countries the primary source is stationary residential. These activities lie in completely different spheres of domestic and international regulation. Moreover, states note that the methodology of data collection is still in development. The non-binding nature of the Arctic Council Framework allows the document to be flexible and adjust in the future, should the science provide a clearer picture.

Conclusions

In the presence of many overlapping treaties and agencies in the Arctic the focus should arguably be on the implementation of existing obligations rather than creating new overarching treaties.18) However, the presence of two separate legal documents covering BC should not be viewed as negative, especially when there is on-going coordination between the two. In addition to utilisation of reporting under CLRTAP for the purposes of the Arctic Council Framework, there are coordination meetings being conducted between the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme and the CLRTAP. While CLRTAP is interested primarily in emissions data at the moment, the Arctic Council is also gathering information on relevant projects and best practices.

The comparison of the two parallel normative efforts to combat BC is important in two respects. First, the correlation between the formal affiliation of a normative instrument with the realm of ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ law and its effectiveness might be overrated. In the present case, states are still reluctant to sign on to binding emission reduction obligations even when there is already a steady decline present due to existing policies. A flexible framework is needed at this stage to be tailored in accordance with an improved understanding of BC sources and effects. This kind of flexibility is best provided by the ‘soft’ law Arctic Council framework. Moreover, the analysis of the first round of submissions under the Arctic Council framework confirms that there is no ‘one-fits-all’ solution for Arctic BC reduction. The primary source of BC differs across the Arctic: while Russia would benefit from further improving its flaring legislation, the Nordic countries are better off focusing on reduction of emissions from wood burning.19)

Secondly, The Arctic Council is growing as a policy-influencer and a ‘learning institution.’20) The BC and Methane Framework demonstrates an improvement from earlier soft-law instruments that were criticized for not being followed-up on. The dominating position of BC on the agenda of the past Canadian as well as the current US Chairmanship at the Arctic Council demonstrates that progress is being made in understanding and regulating this complex issue through a flexible framework.

The article is based on the author’s upcoming paper ‘The Effectiveness of the Regulatory Regime for Black Carbon Mitigation in the Arctic’ in the Arctic Review on Law and Politics.

References