Reading Maps, Reading Extraction Businesses

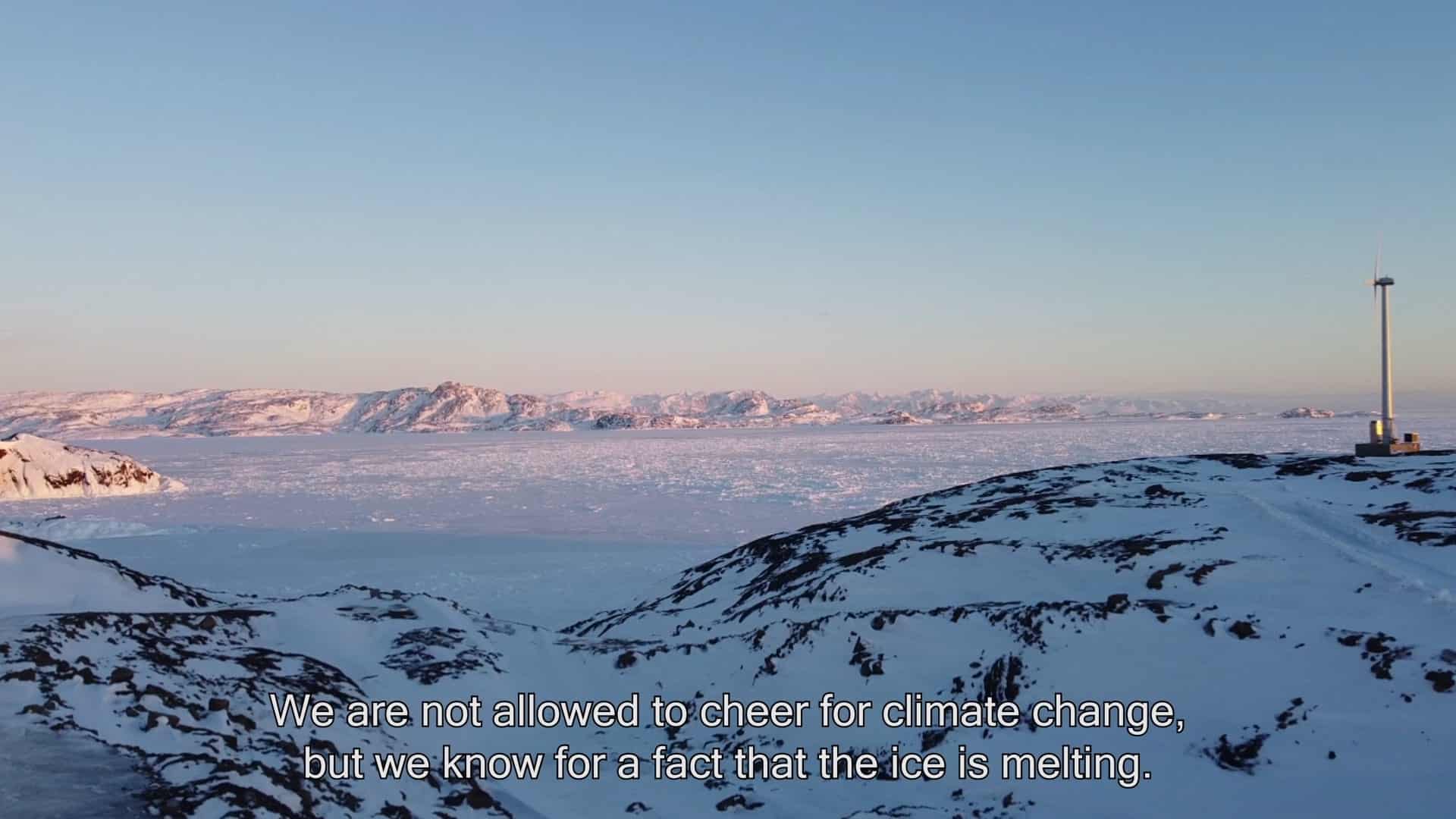

Still from the film Promises For Business. Photo: Gudrun Havsteen-Mikkelsen

The Arctic Institute Arctic Extractivism Series 2024

- The Arctic Institute’s Arctic Extractivism Series 2024: Introduction

- Through Colonial Patterns of Extractivism: Self-Governance as a Sustainable Path Forward

- Leveraging Indigenous Knowledge for Effective Nature-Based Solutions in the Arctic

- Thinking of the Arctic Future(s): When some Scientists precariously Promote Deep-Sea Mining

- EU-Sámi Cooperation in Climate Change Adaptation in the Arctic

- Reading Maps, Reading Extraction Businesses

- The Triangle of Extraction in the Kola Peninsula

- The Arctic Institute’s Arctic Extractivism Series 2024: Conclusion

In Emanuela Casti’s critiques on cartography1) and her semiotic analysis, she argues that that maps are agents with performative aesthetics and realities. According to Casti, maps can generate and amplify political tensions through acts of symbolic control, material control, and finally domination of meaning in contrast to simply storing information.

From maps being intended as a mediation of territory, to maps being active agents that invite processes of resource extraction, it demonstrates that maps indicate the potential for mining businesses. This enhances the double role of maps. On the one hand, maps are intended to transfer knowledge of territory, while on the other hand, are also active agents that invite processes of resource extraction, claiming territories and at the right moment open for investments. However, the paradox of mapping resources, is that it often, if not certainly, leaves the social and environmental issues in the periphery.

As technologies enabled humanity to travel long distances, and document findings of “new” territories, and claim those territories, Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) became in humanity’s perception the last imaginary place2) on Earth – the Terra incognita and later Terra nullius.3) However, the consequences of climate change, Greenland’s strategic military position and its unique and rich geology beneath the Earth’s crust, make the world’s biggest island something more than a frozen wasteland, but a chain of mineral discoveries and deposits reaching into modern times.4) The intensified mapping of raw material and underground mega-structures have over the last years succeeded based on urge to map and extract. Although the world witnesses a shrinking Arctic as the ice cap melts, the global mining sector collectively wants the Arctic to grow. The same mining sector is waiting to be represented in the narrative of a “new” Arctic, as they also see themselves as an important player in accomplishing this influence. This abbreviated article is based on my master’s thesis, Reading maps, Reading business,5) which in broad strokes argues that the processes of mapping and map readings is an act of alteration and territorialization.6)

An example of the map generating domination upon a territory is the Minerals and Petroleum Licence Map. Maps claim to conduct a reality through representation in a visual performance, however the Minerals and Petroleum Licence Map7) may imply different readings; such as vast areas are territories of exploitation and active mining operations (as the polygons are marked in saturated yellow placed on top of coastlines, lakes, rivers, mountains and glaciers), even though only two mines in Greenland are active and in production (anno 2022). What maps signify has, especially in the recent years, been challenged through notions of propaganda in the attempt to claim the conception of reality, to blur the common sense of the world we live in, as an act of domination, and is typically seen in all zones of territorial conflicts. When engaging with the interactive Minerals and Petroleum Licence Map, which showcases the mineral exploration and extraction activities in Greenland, one might believe that more mining activity are occurring than in reality. The semiotics in the map guide the user to analyze and interpret the meaning-systems of the map onto the world. This is the very practice of aesthetic power, when maps with a high level of authority convinces the user about one reality to one specific favor.

Analyzing and reading maps as aesthetic agents can highlight tensions in politics of extraction and visualize the superimposed meanings in the map. A map could just as well support a counter-knowledge or counter-reading of the same specific zone or territory, such as wildlife and population activities where a mine territory is set to be located. Maps replaces rather than represents territory. Certain analyzed maps, such as the Minerals and Petroleum Licence Map, signify tensions that are manifested as a legitimation of action through different levels of symbolic, material and structural control within the maps. These levels of control are seen as an alteration and territorialization of actual territories, which highlight the very point: paradoxes of extractions are situated in mapping.

When analyzing maps, whether they are issued by the extractive industries or governments the map becomes an agency rather than a mediation. Since the map functions as self-referential (meaning that the system within the map is imposing its own lived reality), the map generates information, counting territorialization, rather than simply storing information. As the so-called race for resources is globally being played out by various stakeholders in the Arctic, we can conclude that extracting information from and reading of maps/mapping is a signifier for political tensions and business within Greenland, as it is echoed into global concerns and crisis (the need to develop the green transformation and secure energy).

Gudrun Havsteen-Mikkelsen (DK/IS) is a research-based designer, videographer and visual journalist, who focuses on social, political and environmental narratives and materials in the Arctic region, and its possible future. Gudrun is genially interested in visualising relations and paradoxes between maps and extraction, and she has in the recent years been co-producing content for the podcast Radio Arctic, where she also works as a self-taught cartographer.

References