Polar Expertise in China's 14th Five-Year Plan

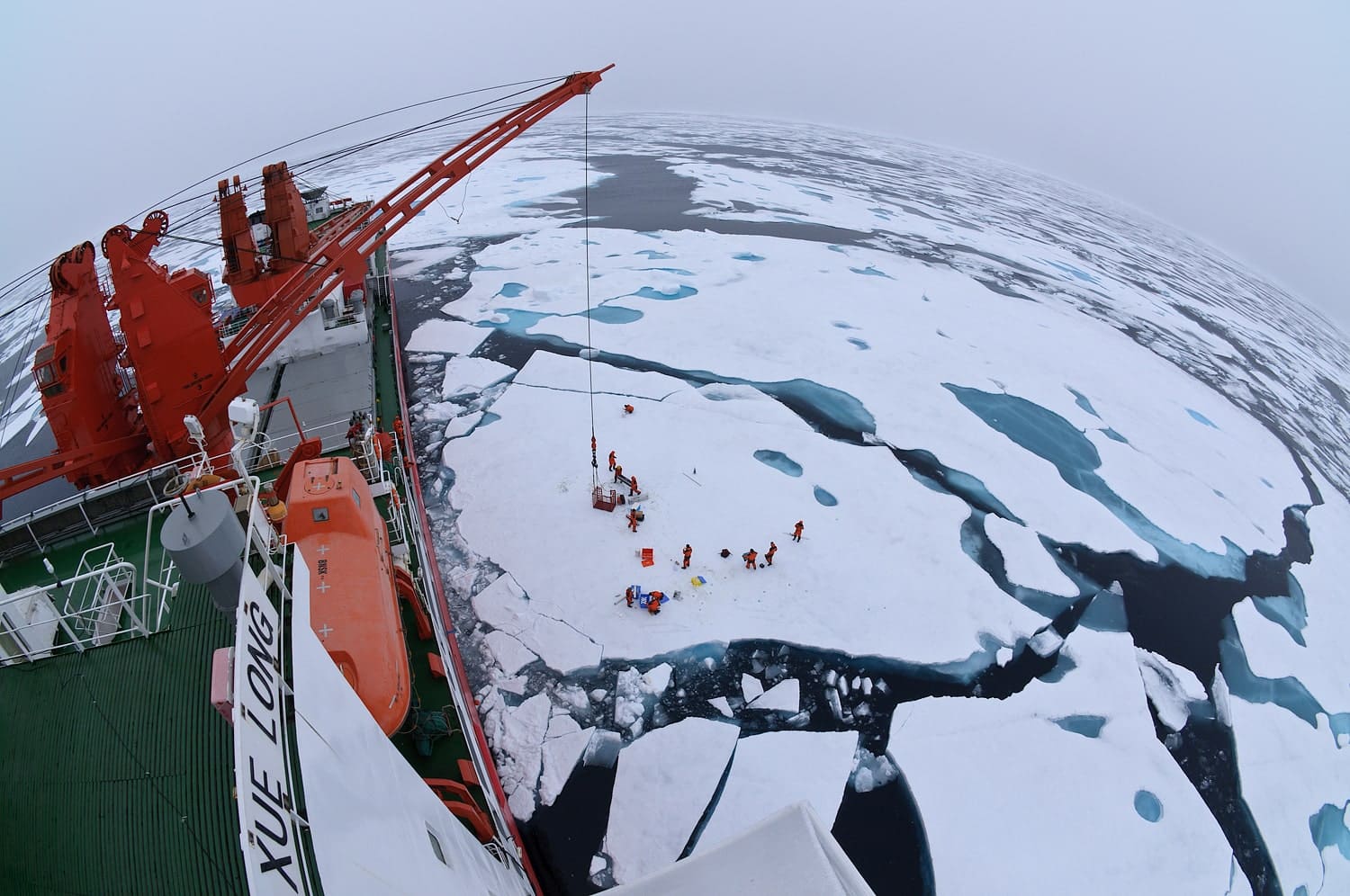

Drift ice camp in the middle of the Arctic Ocean as seen from the deck of the Chinese research icebreaker Xue Long. Photo: Timo Palo

The Arctic Institute China Series 2023

- Chinese Perspective on the Arctic and its Implication for Nordic Countries

- China and the Arctic: Reflections in 2023

- China’s Polar Silk Road: Long Game or Failed Strategy?

- The Arctic for China’s Green Energy Transition

- Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine: Impacts on China’s Climate Responsibility in the Arctic

- What the 14th Five-Year Plan says about China’s Arctic Interests

- The Arctic in China’s Subnational 14th Five-Year Plans

- Polar Expertise in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan

- China and the Arctic in 2023: Final Remarks

Science makes up the bulk of China’s activities in the Arctic. In past five-year plans, sections on science and technology have been the places to look for mentions of the Arctic. This is true for the fourteenth Five-Year Plan, too.1) In Chapter 4 (“Strengthening national strategic science capabilities”) of the new national plan, the development of heavy icebreakers and the establishment of a “three-dimensional polar observation platform” are listed as priority areas.2) The plan also states that the second phase of China’s polar expedition program will launch during the current five-year plan period.3) This program was initiated by the State Oceanic Administration, an agency which, prior to being incorporated into the new Ministry of Natural Resource in 2018, was tasked with developing China’s ocean policy. The program was launched in order to improve China’s “operational capabilities and governance capacity in the polar regions,” with the goal of turning China into a “polar great power.”4) In other words, to grow the country’s polar expertise.

Sprinkled throughout the national five-year plan are also other, more general items with implications for the Arctic. The plan calls for upgrading the country’s shipbuilding and marine engineering base and developing advanced marine technology,5) achieving global coverage with China’s homegrown satellite navigation and remote sensing infrastructure,6) boosting the development of small modular and marine nuclear reactors,7) and for the country’s scientific communities to take a more active part in international research projects.8)

The National Natural Science Foundation, China’s main funder of basic research, includes in its own five-year plan a section on “marine processes and polar environments,” stressing polar climate change research, tri-polar cryospheric research between the Arctic, Antarctic, and the Tibetan Plateau, as well as ecological and infrastructural safety related issues arising from polar warming. A second section of the plan is concerned with the design and maintenance of polar and deep-sea research infrastructure, such as for polar underwater acoustics research.9) A five-year plan issued jointly by the National Development and Reform Commission and the China Meteorological Administration calls for improving the country’s remote sensing and meteorological monitoring capacity along the Belt and Road as well as in the Arctic and Antarctic regions; achieving full satellite remote sensing coverage of important marine areas and shipping routes; establishing a global blue-water navigation service using domestic technology; and, to explore the development of a weather service for Arctic sea routes.10)

Subnational plans

Polar technologies and research have also found their way into provincial five-year plans.11) The coastal province of Zhejiang, for example, plans to accelerate the development of ice-strengthened vessels, according to the five-year plan for the province’s manufacturing industry.12) Neighboring Jiangsu province plans to strengthen development of polar cruise vessels.13) Liaoning similarly lists polar research icebreakers and improving the country’s “polar observation system” among the maritime technologies it will focus on, with plans to establish a provincial “polar maritime technology innovation center.”14) A subsection of Shandong province’s shipping and maritime engineering five-year plan is dedicated to polar shipping, with heavy icebreakers and “polar deep-sea exploration vessels” listed as key technologies.15) Shanghai has included polar research and the development of polar technologies in its five-year plan to become a global center for innovation, noting that it will build polar-going vessels and boost China’s capacity to develop polar technologies.16) The megacity’s five-year plan for its “strategic industries” likewise includes icebreakers in its list of marine technologies to pursue.17) But more noteworthy is the province of Heilongjiang, which lists equipment for underwater operations in the polar regions, a “polar maritime emergency platform,” and nuclear icebreakers as priorities for the province’s research institutions.18)

Nuclear icebreakers were first introduced during the 13th Five-Year Plan period, when the technology was included in a plan for the country’s “strategic emerging industries” alongside several other polar-related technologies.19) Several state-owned companies and research institutes have since embarked on a project to develop such vessels.20) The Heilongjiang provincial plan looks to be the only plan that makes a mention of the technology this time around. But leading up to the adoption of the current five-year plan, a deputy chairman of China’s National Nuclear Strategic Planning Research Institute included nuclear-powered icebreakers in his recommendations for the upcoming plan.21) Experts have also emphasized polar vessels as a commercial shipbuilding niche. At the 2020 INMEX maritime industry convention in Guangzhou, a representative from the National Marine Data and Information Service argued that for the 14th Five-Year Plan period, China’s shipbuilding industry should make efforts to boost the country’s market share when it comes to higher value-added ship types, such as polar icebreakers.22)

National key research and development programs

More clues about China’s evolving Arctic interests and capabilities can be found in the many research projects being commissioned for the current five-year period. The Ministry of Science and Technology has published funding guidelines for several so-called “National Key Research and Development Programs.” These programs have been set up to support research and direct funding toward areas considered to be strategically important. Among the topics included in the current funding round, both the “Earth Observation and Navigation Program” and the “Key Technologies and Equipment for the Deep Sea and Polar Regions Program” heavily feature the Arctic, with the latter offering funding for the development of “technologies, equipment, and systems for utilizing polar resources and protecting polar environments,” and to improve China’s “polar monitoring and forecasting capabilities.”23) The guidelines go on to list a handful of polar projects and technologies, among them shipboard cranes designed for heavy lift operations involving manned submersibles and polar-capable unmanned amphibious vessels.24)

Also included in these plans are projects with more direct connections to Beijing’s Polar Silk Road vision. Specifically, the ministry is looking to fund research on communication and navigation technologies for maritime activities in the Arctic that uses the country’s homegrown BeiDou Navigation Satellite System. Moreover, the guidelines call for the complete “indigenization” of sea ice remote sensing technology, with the reasoning that, “considering the importance of sea ice detection for Arctic shipping, polar research, and climate change, and China’s weak polar observation capabilities,” there is now a need to “make domestic breakthroughs in satellite-based remote sensing technology for sea ice in the Arctic, and to develop fully independent sea ice remote sensing systems and products.”25) These documents also set out deliverables such as developing shipboard integrated radio communication systems and navigation systems that can reliably receive ice chart information using the BeiDou satellite network; developing an information platform for navigation in the Arctic; a database of nautical charts “covering more than 80 percent of the Northeast Passage;” and, oddly specific, “30 nautical charts for the Northwest Passage.”26) The documents also list the development of high-resolution microwave sounding technology and the use of aerial remote sensing in the Arctic, both framed as steps toward developing regional shipping.27) Previous funding programs have stressed the need to deepen science cooperation with Arctic states. Guidelines from 2018, for example, include the following objectives: “Constructing one Arctic ground station able to receive data from no less than five China-European satellites,” and establishing “two to three joint observation stations in the Arctic in order to provide China-European satellite-based remote sensing monitoring and forecasting products and for supporting research vessels and commercial traffic in the Arctic.”28)

But hard technology is not the only focus. Attention is also being paid to the softer aspects of navigating the Arctic. The ministry urges researchers to “comprehensively study the international conventions and national regulations governing Arctic shipping routes.”29) Similar guidelines published in 2019 emphasized legal research about the Arctic and called for forging closer collaborative ties with research communities in the region, setting the target to “establish international polar cooperation mechanisms with no fewer than two countries/regions” during that five-year period.30) This links back to the goals of improving China’s governance capacity in the polar regions and building up its domestic Arctic expertise.

Arctic expertise

By looking at its five-year plans and other related, more technical planning documents, we can better trace the contours of China’s evolving interests in the Arctic. The relative dearth of Chinese activities in the region should impel researchers to examine developments taking place domestically instead. The key role played by science and technology in Arctic geopolitics also means that documents detailing such developments can act as a useful proxies for understanding countries’ Arctic ambitions.

The outsize focus on remote sensing, communication, and monitoring technologies in China’s five-year plans demonstrates this. In the absence of any Arctic territory, research programs and remotely operated sensors allow non-Arctic states like China to develop a degree of situational awareness in the region. Climate research, shipping, and resource development all demand information by Arctic environments. Moreover, by boosting its knowledge about the Arctic, China can also grow its position as a regional knowledge producer and, in turn, improve the way it participates in regional governance.31)

Speaking at the Arctic Circle Forum in Tokyo in March, Gao Feng, the country’s special envoy on Arctic Affairs, reiterated the four pillars of China’s Arctic policy: To understand, protect, develop, and participate in governing the region. But, he stressed, that first pillar, to understand, is becoming more and more important.32) Studying how China is gearing up to better understand the Arctic, politically as well as environmentally, should be a focus for research that wants to understand the country’s trajectory in the region.

References