Perspective Correction: How We Misinterpret Arctic Conflict

War and conflict sell papers — the prospect of war, current wars, remembrance of wars past. Accordingly, a growing cottage industry devotes itself to writing about the prospect of conflict among the Arctic nations and between those nations and non-Arctic states, which is mostly code for “China.” As a follower of Arctic news, I see this every day, all the time: eight articles last week, five more already this week from the Moscow Times, Scientific American or what-have-you. Sometimes this future conflict is portrayed as a political battle, sometimes military, but the portrayals of the states involved are cartoonish, Cold-War-ish…it’s all good guys and bad guys.

I’m convinced that this is nonsense, and I feel vindicated when I see the extent to which these countries’ militaries collaborate in the high North. From last week’s meeting of all eight Arctic nations’ military top brass (excepting only the US; we were represented by General Charles Jacoby, head of NORAD and USNORTHCOM) to Russia-Norway collaboration on search & rescue; from US-Canada joint military exercises to US-Russia shared research in the Barents…no matter where you look, the arc of this relationship bends towards cooperation.

But there’s a bigger misconception that underlies the predictions of future Arctic conflict that we read every week. This is the (usually) unspoken assumption that the governments of these states are capable of acting quickly, unilaterally and secretly to pursue their interests in the Arctic. False.

This idea that some state might manage a political or military smash-and-grab while the rest of us are busy clipping our fingernails or walking the dog is ridiculous. The overwhelming weight of evidence suggests that the governments of the Arctic states are, like most massive organizations, bureaucratic messes. Infighting between federal agencies is rampant all around, as are political shoving matches between federal and state/provincial/regional governments. Money is still scarce, and chatter about military activism isn’t backed up by much: Canada is engaged in a sad debate over the downgrading of the proposed Nanisivik port; the United States’ icebreaker fleet is barely worth mentioning and shows little sign of new life in the near-term future; US Air Force assets are being moved 300+ miles south from Fairbanks to Anchorage; and Russia’s talk about a greater Arctic presence has been greatly inflated for the sake of the recent elections. In a more general sense, we have viciously polarized governments in the US and, to a lesser extent, Canada, as well as numerous “hotter” wars elsewhere that will take the lion’s share of our blood and treasure before the Arctic gets a drop of either.

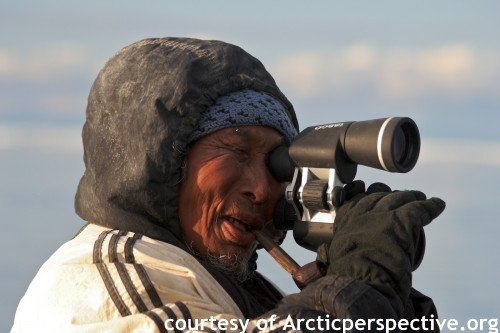

The smaller states might be able to act more nimbly, but Norway and Denmark are successful Scandinavian social-market economies with modestly-sized militaries who aren’t likely to put military adventurism in the Arctic at the top of their to-do lists. They’re also patient decision-makers who are making apparently sincere (if not always successful) efforts to incorporate their resident indigenous communities into national politics. This makes fast, unilateral, secret action unlikely.

And then there is Russia. From the outside, it can often seem as though the Russian government rules by fiat. This reasonably leads to the concern that someone might take it into his head to assert Russia’s military might or otherwise extend the country’s sovereignty in the Arctic. But it is fairly clear that Russia’s success is currently, and for the near-term future, dependent on its position within the constellation of global hydrocarbon suppliers. To continue to develop its supply base, Russia needs the assistance of the oil majors of neighboring states, and indeed it is showing signs of warming up to foreign engagement with its Arctic hydrocarbons in significant ways. Its political relationships with its regular customers are also critical to its future success. Russia isn’t likely to wantonly sour those relationships by acting aggressively against all four of its wealthy, well-networked littoral brothers in Europe and North America.

It’s not only the handcuffs of many colors worn by the Arctic states that will keep them from getting aggressive, it is also the good precedents that exist for cooperation here. Russia and Norway recently resolved a forty year-old dispute over territory in the Barents. There are regular examples of military cooperation among the four littoral NATO states and between Norway and Russia. Even the US and Russia are finding opportunities to work together. Meanwhile, the need to develop search-and-rescue capabilities is making cross-border cooperation a necessity for all Arctic actors. There are numerous international research and private-sector ventures, even in areas other than hydrocarbons. These will only grow in importance with time. In fact, it would seem that for many of these countries, the Arctic is a welcome relief – a site where international collaboration is comparatively amicable.

But there is indeed a competition underway in the Arctic. It isn’t between states; it is the competition between categories of actors to set norms and precedents that, though unwritten, will guide the development of the region. We see this competition in the complicated jockeying between states, indigenous organizations, the Arctic Council itself, academia, military coalitions (e.g. NATO), extractive industries and environmental groups, among others. The central prize is neither oil, nor data, nor pristine wilderness but instead the privilege of deciding which issues enjoy the sunlight of attention and which are dealt with quietly in the shadows. Many venues exist already for debate and conflict resolution, but who will decide which issues make it onto the docket in these venues? Perhaps more importantly, who will get to decide what the public hears and learns to care about? It may be that, for the moment, the hydrocarbon industry is doing a good job of pressing its suit. Its victories set precedents for elsewhere in the Arctic, but they also imply suboptimal outcomes for other classes of actors, who will be adapting and innovating to better press their cases in different venues and through different channels.

There are many Arctic issues already settled by UNCLOS and other legal regimes. But there are also numerous issues yet to be resolved, and the letter of existing law is rarely so iron-clad that there is no room for interpretation. As the North becomes the focus of increasing interest, which category of actor will be writing the rules? Time will tell.