Northern Corridor for Central Asia-Arctic Ocean Transport Access

River port infrastructure in the Ob’ river basin. Photo: Ales Antonovich

Russian rivers famously ‘go the wrong way.’ The United States and Canada have the beneficial hydrography of the interconnected Great Lakes system and the Mississippi, and Europe has the Rhine, Elbe, Danube, and Dnieper inland waterways which gives even landlocked states such as Switzerland and Austria direct access to the ocean and the favourable costs that maritime transport bring to trade. But for Kazakhstan, one Russian river does ‘go the right way.’ The Ob’-Irtysh river system penetrates deep into the heart of Eurasia, offering Central Asian states an avenue for directly accessing ocean trade lines.1)

The Russian Federation stands to be a net beneficiary of climate change. Melting Arctic multiyear ice is rapidly opening possibilities for Northern Sea Route (NSR) operations with more ice-class vessels, fewer icebreakers, more LNG transit and containerised transport, and more international transshipment ports and multimodal port operations. However the developing geoeconomic competition in Eurasia between China, Russia and Central Asian states means that inland river transport also has a geoeconomic security aspect.2)

An increase in NSR traffic offers a natural piggy-back development possibility for opening Eurasian inland river transport to connect to the Arctic with less frozen-river time and more navigation days per year. A warming climate only makes more of Eurasia accessible to maritime transport and inland waterway navigation. Russia’s climate change geographic capital can thus be extended to offset the traditional ‘geography tariff’ borne by Russia’s neighbours, in Kazakhstan and Mongolia, and deeper into Central Asia and China.

While these inland waterway connections could synchronise with expanding trans-Arctic shipping, any development of inland river or Arctic Ocean transport systems carry water security, transboundary security, and ecological security risks. Arctic transport development will also likely not only encourage the reemergence of regionalisms, and restrengthen geoeconomic regional agendas, but will also necessitate institutional strengthening of environmental monitoring, mitigation and remediation systems. The advance of a Eurasian inland waterway transport system will thus have serious consequences for both geoeconomic and environmental security for the polities and biomes which development may service.

Inland Transport Development in Eurasia

Kazakhstan’s inland waterways are extremely underdeveloped. Kazakhstan has over 4,000 kms of navigable inland waterways, comparable with the Western European industrialised economies of Germany and France. While Kazakhstan could never rival a state like the Netherlands for inland waterways, the natural geography presented is similar to Switzerland on the Rhine or Austria on the Danube: deep inland developed economies with access to the global ocean for trade.

China’s Belt and Road transport policies in the Central Asian economies have come with media hype on the supposed benefits of the shorter transit times offered by the China Rail Express intercontinental rail corridors connecting China and Europe via either Russia or the Black Sea.3) The argument is that there is sufficient demand for goods with transport time needs shorter than maritime but cheaper than air freight, and that these increased transcontinental rail services will help to build economies of scale.4)

However, for the Central Asian economies on the East-West facing Eurasian rail network— Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan—transit time is far less important than transport cost. Maritime trade is vastly cheaper than rail or road transit and almost universally preferable unless cold-chain storage or just-in-time inventory supply chain management are important. The consumer pays the transport tariff, with the Central Asian consumer consequently paying a tariff simply due to geography.

The cost of Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit (TEU) container imports into Kazakhstan’s Aktau port or Turkmenistan’s Turkmenbashi port are already comparable with Mediterranean, Black Sea, and Indian Ocean transport costs. If Central Asia’s consumer cities were located on the Caspian Sea, then transport costs would be comparable to Europe. However, rail and road transit to inland cities in the far east of the region in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan contribute well over 100 percent of the cost of transporting a TEU from Europe to the Caspian Sea.

A Northern Corridor, as a North-South axial multimodal transport corridor reaching Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan towards northern Siberia at the Kara Sea connecting to the NSR, could link the region to global ocean trade. This route would always be more expensive than connecting two warm-water ports in the Atlantic, Indian or Pacific Oceans. But development of a Eurasian inland waterway transport system to connect to the Northern Sea Route could become a second-tier alternative for Central Asia to reach global markets.

A New Vector for the Northern Sea Route

The dearth of inland waterway transport in post-Soviet economies is not due to lack of favourable geographical conditions, political vision, or poor built-environment. Rather, inland waterway development throughout the former Soviet Union and its satellites has faced a decumulation period. While inland waterway use in Poland, Romania, and Hungary collapsed after 1991 and started recovering under UNECE development, the Soviet Union’s quite active intra-Arctic shipping and inland waterway transport systems that crashed, have yet to recover under independent Russia and Kazakhstan.

Central Asian economies are traditionally analysed as landlocked, however, the combination of inland water transport on the Ob’-Irtysh river system and a thawing Arctic Ocean, making the Northern Sea Route viable, opens the possibility for increased maritime transport directly from Kazakhstan to both Europe and East Asia. The Northern Sea Route connects Russia’s Sabetta port with the Northeast Asian shipping lines centred on Dalian, Qingdao, Zhoushan, Yokohama, Busan, and Kaohsiung and with the North European ports, Rotterdam, Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Antwerp, Zeebrugge, and Le Havre. For Central Asian economies to have access to these shipping lanes at costs comparable to those enjoyed by European inland economies would be a huge economic advantage. If it works for the Rhine and the Danube, why are the Volga, Don and Ob’ so underutilised?

Even without the prospect of the Northern Sea Route opening an inland waterway to direct maritime trade, greater development and integration of Russia’s inland waterways with Central Asian economic and transport development would be desirable. And yet, the Ob’-Irtysh river system has inadequate port infrastructure, small fleets, ageing infrastructure, poor natural river course maintenance, and nearly no canalization.

This route would likely never become a primary trade route for Kazakhstan or the other Central Asian States. But maintaining the possibility of cheaper, Summer, water-borne trade into the Eurasian landlocked economies is a prospect which could save Central Asian consumers the costs of the natural geography tariffs they are currently subject to. Multilateral economic development agencies already support development of second-tier transport alternatives, such as the CAREC Corridor system’s extant use of Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Pakistan as viable transport routes.

Expanding Sabetta port infrastructure into containerised shipping opens the possibility for intra-Arctic transshipment infracture, connecting transhipment ports in Kirkenes and Finnafjörður in Europe and the new LNG transhipment port development in Kamchatka.5) Development of multimodal containerised transport towards Europe is the most viable, with shorter distances, advanced multimodal infrastructure and the development of North-minded logistics projects such as the Arctic Corridor.6)

The challenge for Kazakhstan and other Central Asian economies is not the NSR. Rather it is the need to organise, plan and invest in road, rail and inland waterway transport infrastructure to develop a Northern Corridor connecting Kazakhstan’s existing national logistics network, the Bishkek-Almaty corridor and the Tashkent-Shymkent-Khujand corridor. Connecting Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan into an Arctic Ocean maritime transport vector focused on a containerized port in Sabetta would leverage the ongoing developments of intra- and trans-Arctic shipping.

Geoeconomic Integration and Security

Despite the hype surrounding Belt and Road investment in Eurasian rail transport, the European Union provides more assistance to Central Asian transport development than China, and UNECE offers a cleaner model of multilateral transport integration and standardisation.7) European transport integration with Central Asia and Eurasia is an economic good, and one which aligns with the direct assistance and other European Union and European state mechanisms for economic development assistance for Central Asian economies.

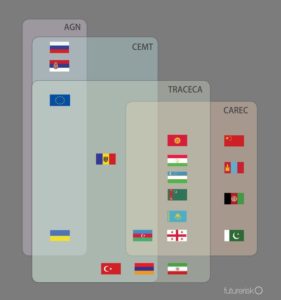

The existing international legal framework and multilateral institutions favour a regionalist approach to European transport integration with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic and Uzbekistan. Kazakhstan should sign, ratify and accede to the European Agreement on Main Inland Waterways of International Importance thereby joining the multilateral standard for inland waterways governance first developed by UNECE and which the Russia Federation now also works under.8)

This would not only provide clear pathways to industrial standardisation and regional integration but would also encourage statistical collection by the Central Asian economies allowing for aggregation at the European Union and UNECE levels. Regional institutions are likely to increasingly replace globalisation institutions as globalisation retreats. For a functional inland waterway regionalism to work with Russian and Central Asian partner economies, the clearest path to success is to join the existing regional forms of multilateral, international law based institutions.

Central Asian economies remain a geoeconomic periphery. From a China perspective, developing road and rail links from Kashgar and Khorgos to Central Asia, Pakistan and Afghanistan is geoeconomically strategic. However, for genuine market-based transport systems to deliver lower goods costs to consumers in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, regional transport development plans must focus on strategies which benefit the independent states of Central Asia.

Focusing on cluster development rather than economic corridors should prioritise exports and manufacturing centres in the clusters along the corridors. Multimodal transport and economic development are complementary. The development of modal economic clusters and linear economic corridors in Central Asia can both agglomerate capital and cumulatively attract secondary and tertiary industries. Investing in Kazakhstan’s dilapidated inland ports at Pavlodar, Semey and Ust-Kamenogorsk would be capital investments that could deliver multiplier benefits across a range of industries and exports, as well as addressing Kazakhstan’s import cost problem.

Multiple second-tier transport alternatives such as the Northern Corridor can become economic vectors for Central Asian economies, connecting across both the Arctic Ocean and the Caspian Sea. Any investment in transport development in Central Asia’s Arctic vector should prioritise the economic benefit of the people of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan. However, these investments should be measured in increases in speed and tonnage; and decreases in freight prices. Development of transport corridors should not depend on the grand geoeconomic plans of either Russia or China.

The Northern Corridor opens greater possibilities for economic development for these land-locked Central Asian economies. And it offers the European economies a simple path towards integrating new market-focused economies and consumer populations in Central Asia. Reintegrating Kazakhstan’s broken inland waterway system would benefit consumers all along the transport corridor. The trade potential for opening Central Asia to Europe and East Asia via an Arctic Ocean shipping vector changes the dynamics of the current multilateral assistance approach to economic development in the region. For Central Asian trade and logistics development, the Northern Corridor provides both an economic and a geoeconomic alternative to either the dependency of land-locked economic development or the false promise of the Belt and Road.

Tristan Kenderdine is Research Director at Future Risk and Executive Editor at Hansa Press.

References