Non-State Actors in the Arctic: Lessons from the Centennial of the Svalbard Treaty Negotiations

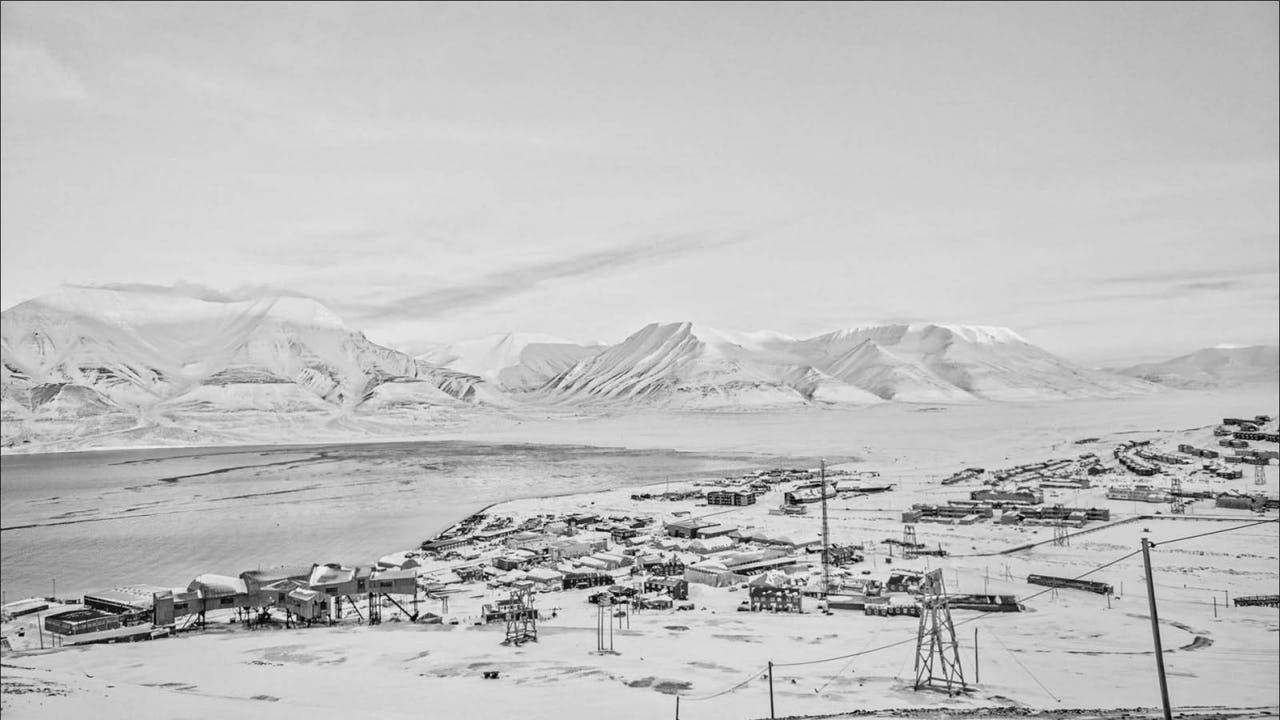

Longyearbyen is the largest town and the center of government in Svalbard. Photo: Hurtigruten Svalbard

The centennial year of the Paris Peace Conference offers an opportunity to celebrate a seminal moment in the history of diplomacy. A small and often forgotten part of the 1919 peace talks was the resolution of the Svalbard Question (the name of the archipelago was changed from Spitsbergen to Svalbard in 1925; I will use Svalbard anachronistically throughout to avoid confusion).1) A centennial is not only a time to reflect on past events, but also an opportunity to think about the future. What lessons does the Svalbard Question2) and its resolution offer for contemporary Arctic governance? The Svalbard Treaty of 1920, while innovative at the time because of its careful balance of Norwegian sovereignty with equal access rights for other countries3), has suffered from the need to reconcile it with subsequent developments in international law, such as the expansion of territorial waters and the creation of exclusive economic zones, whose status is ambiguous in the Treaty.4) As Alyson Bailes puts it, “treaties are victims like everyone else of the passage of time” and as such “a version of the Spitsbergen Treaty writ large is not a viable answer for tomorrow’s Arctic.”5) This article proposes that the historical value of the Svalbard Question is found not in its legal resolution, but in the way that non-state actors contributed to that resolution. In a changing Arctic that presents increasing challenges to a limited state-centric view of Arctic governance,6) a historical example of the importance of non-state actors in the Arctic is all the more valuable.

This article begins with a discussion of how non-state actors were empowered by Svalbard’s lack of state sovereignty in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. It then explores how these actors influenced the outcome of the Svalbard negotiations. This article focuses on two main types of non-state actors: corporations and the group of scientists and explorers that Elen C. Singh terms the Svalbard “Literature Lobby.”7) These groups are not so easily separated, as will be shown later. The analysis relies primarily on Singh’s book-length account of American diplomacy involving Svalbard, with the addition of scholarly articles that explore the British experience. It also analyzes several of the works of the “Literature Lobby” to show their power to influence the negotiation process. Finally, the article concludes with an exploration of lessons to be drawn from the Svalbard negotiations for the contemporary Arctic.

A Medieval Analogy

From the nineteenth century onward, Svalbard was not claimed as territory by any nation.8) It was, therefore, understood to be terra nullius—no man’s land. The history of the concept of terra nullius is complicated and still not completely understood. It evolved out of the legal concept of res nullius, which means an object not owned by anyone.9) Terra nullius originated in the first decade of the twentieth century, although the meaning of the term was in flux during the negotiation of the status of Svalbard. As Christopher Rossi puts it, “what did terra nullius mean in Spitsbergen’s twentieth century context? Did it preclude possession by states as a confused or commingled expression of res communis? Did it imply a condominium arrangement among interested parties? Did it require formal multilateral legal administration through treaty creation? Or did it express a beachcomber’s delight, bestowing treasures on privateers who were lucky or capable enough to fall first into possession of ownerless property? Each of these usages attached to the meaning of terra nullius in Spitsbergen’s history…”10)

What is clear is that Svalbard posed a challenge to the paradigm of sovereignty in the early twentieth century. Perhaps this conflict can best be understood through reference to a medieval analogy.11) Stephen J. Kobrin argues that “the medieval to modern transition entailed the territorialization of politics, the replacement of overlapping, vertical hierarchies by horizontal, geographically defined sovereign states.”12) This modernization occurred throughout Europe during the early modern period, but seems not to have taken place in Svalbard, likely due to its remoteness and difficult environment. Svalbard thus emerged in its modern period (after 1871) as a region unclaimed by states but with occupants of increasing permanency from a number of different European countries. When national governments attempted to resolve the Svalbard Question, they were forced by the absence of historical state activity to rely on the words and deeds of non-state actors to generate claims of sovereignty and assess their value. One significant source of guidance was corporate entities which, in return, requested government assurance of property rights on the archipelago. The next section will briefly outline the emergence of coal mining corporations on Svalbard and describe their role in the Svalbard negotiations.

Corporations, Lobbying, and the Svalbard Question

Economic activity has a long history in the Svalbard archipelago. Whaling began in the region only a few years after Willem Barentsz first sighted the archipelago in 1596.13) Competition between English and Dutch whalers lasted throughout the first half of the seventeenth century. This activity decreased in the latter half of the century due to changing ice conditions and exhaustion of the whale stocks. In the eighteenth century, Russian walrus hunters known as Pomors occupied the archipelago. Large-scale settlement of Svalbard came only at the end of the nineteenth century with the emergence of industrial coal mining. The archipelago’s coal mining companies would later come to exert outsized influence on negotiations regarding Svalbard.14)

A number of British mining companies emerged on Svalbard, but the Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate and the Northern Exploration Company quickly developed into the most important ones. The Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate was founded in 1908 by William Spiers Bruce, a renowned Scottish polar explorer. Bruce leveraged his reputation as an Arctic expert to gain support for the enterprise, in an example of the often blurry distinction between corporations and the “Literature Lobby.” In 1912, Bruce lobbied the British government to consider annexing Svalbard to secure property rights. He and other enthusiastic members of the Royal Geographic Society, an organization that traditionally avoided overt political activism, attempted to influence the decision of the British government. This deviation from the typically apolitical public stance of the Royal Geographical Society shows the importance of the Svalbard Question in certain sections of British society that perceived themselves to have a significant influence in governmental decisions. Ultimately, the British government chose not to take action during the Paris Peace Conference despite Bruce’s lobbying, likely because it was far more interested in German territories that would soon become British mandates.15)

The American government was far more receptive to corporate lobbying on the Svalbard Question than the British government. Frederick Ayer and John Longyear founded the Arctic Coal Company in 1906. The company purchased land in Svalbard and was in frequent contact with the US State Department to make sure that its property rights would be protected. As seemingly the only American actor that was interested in Svalbard, the Arctic Coal Company exerted significant control over American policy in the region.16) From 1909 to 1910, the Company attempted to secure passage of legislation that would allow an American claim of sovereignty over Svalbard. The bill was ultimately dismissed for fear of international repercussions.17) Longyear and Ayer continued to influence the State Department’s Svalbard policy by lobbying for the avoidance of negotiations that they thought would lead to Norwegian sovereignty and the introduction of taxation.18) They even made the remarkable suggestion that Svalbard be run by an international corporation with a portion of its stock available for purchase by participating nations.19) The Arctic Coal Company’s considerable influence over the US State Department finally ended in 1916 when it sold off its land claims in Svalbard at a loss due to substantial legal and lobbying costs.20)

The Svalbard Literature Lobby

The influence of non-state actors on the Svalbard negotiations was not confined to corporations. Another significant group in the negotiations was the Svalbard “Literature Lobby.” Elen C. Singh uses this term to refer to publications written during the 1910s that attempted to persuade national governments to take a specific position on the question of Svalbard’s sovereignty. Lobbyists from the Netherlands explored the role that the Dutch had played in Svalbard’s early history. British and American lobbyists primarily detailed the economic utility of the archipelago and the presence of companies run there by their nationals. Norwegians compiled a robust record of Norway’s historical and contemporary presence in Svalbard to demonstrate that it ought to be granted to Norway. Prominent members of the “Literature Lobby” were the French naturalist, Charles Rabot, the Norwegian geologist, Adolf Hoel, and British scientist William Speirs Bruce. These writers published newspaper articles, scientific journal articles, and even full-length books. They addressed topics such as Svalbard’s settlement history, the economic value of the archipelago, and the legal rights possessed by various nations.21)

As the United States no longer had any business interests in Svalbard after the Arctic Coal Company’s 1916 liquidation, American authors were largely in favor of Norwegian sovereignty over the archipelago. Svalbard had become an interesting legal and philosophical issue, instead of a concern involving American interests. Robert Lansing, who later became the American Secretary of State, told foreign ministers that he favored Norwegian sovereignty as the solution that was most likely to reduce tensions in the region.22) He wrote an article for The American Journal of International Law that considered Svalbard merely as “A Unique International Problem,” albeit one that had been opened by “American enterprise and energy.”23)

British writers in the “Literature Lobby” were far more passionate than American authors. R. N. Rudmose Brown, the Scottish explorer and Bruce’s assistant, detailed the history of the Svalbard archipelago in the 1919 article, “Spitsbergen, Terra Nullius.” He listed a number of important British explorations in the region and claimed that “no living man knows more of Spitsbergen than Dr. W. S. Bruce.” He cast doubt on Norwegian claims because they were “late in the field.”24) Brown argued that Svalbard was terra nullius, but acknowledged that the lawless situation on Svalbard was unacceptable. Britain had “an undeniable claim” and Norway had developed key infrastructure on the archipelago. The best solution, according to Brown, was an agreement between the two countries that either granted sole sovereignty to one of the nations or allowed joint control.25)

Charles Rabot, a French supporter of Norwegian claims to Svalbard, had a strikingly different historical story to tell. In his 1919 article, “The Norwegians in Spitsbergen,” Rabot criticized previous writers for ignoring “the great work done by the Norwegians in this archipelago.” He emphasized the presence of Norwegian walrus hunters on Svalbard in the latter half of the nineteenth century.26) With respect to industry, Rabot claimed that “the best-developed collieries [coal mines] in Spitsbergen belong to Norwegian companies.” The British, by contrast, were deemed “far behind.”27) Rabot’s most startling argument was that Svalbard was not terra nullius, but rather a Norwegian possession by inheritance of a seventeenth century Danish claim. Rabot maintained that the “sovereignty is not complete, not having been recognized by all the powers.”28) Nevertheless, his article seemed to suggest that the historical claim, combined with de facto Norwegian occupation of Svalbard, should have been sufficient grounds for full Norwegian sovereignty.

Members of the “Literature Lobby” were able to exploit their knowledge of Svalbard and their standing as experts to try to shape diplomatic discourse in ways that would contribute to national or personal gain. While the precise impact of these documents on the final outcome of the negotiations is difficult to ascertain, they were undeniably read and used as background information by diplomats, as is evidenced by the citation of Brown, Bruce, Lansing, and others in the American government’s preparatory document for the Svalbard negotiations.29)

Lessons for the Modern Arctic

This article began by asking what lessons the Svalbard Question and its resolution can have for modern practitioners of Arctic geopolitics. The subsequent demonstration of how corporations and the “Literature Lobby” used their knowledge of Svalbard and governmental reliance on them for information to control the diplomatic discourse shows that no understanding of the Svalbard negotiations can exist without recognizing the significant roles played by such non-state actors. Similarly, contemporary Arctic politics cannot be understood without an appreciation of the contributions and challenges produced by non-state actors. Indeed, the parallels between the Arctic non-state actors of the 1910s and the present day should be further explored. Similar groups, such as corporate lobbyists, scientists, and the media, are important components in both periods of Arctic politics.

Lobbying on Arctic issues, especially in the United States, has allowed corporations to have an outsized say in government policy, both during the Svalbard negotiations, and in recent years. It is very unlikely that the monopoly on the State Department’s Svalbard policy held by the Arctic Coal Company in the 1910s will reappear in the modern day. Nevertheless, the Arctic remains relatively obscure to the American public, which allows corporations to make significant lobbying efforts while maintaining a low profile. The Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, for example, “has spent millions of dollars over the past two decades to convince Congress to overturn a prohibition on drilling” in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, but is “largely unknown outside Alaska.”30)

Scientists play a significant role in Arctic policy as participants in the Arctic Council’s Working Groups. They are also involved in the contentious area of territorial claims in the Arctic. Under the Convention on the Law of the Sea, scientific claims about undersea ridges have tremendous importance for determining the scope of exclusive economic zones.31) The involvement of scientists in such inherently political research risks the politicization of science to further national ends. Just as the entry of Royal Geographical Society into disputes over Svalbard’s sovereignty weakened its publicly apolitical persona, the contemporary politicization of science threatens to undermine its authority on major environmental issues, particularly climate change.32) Mass media also has an important impact on the politicization of the Arctic region. Their effect on public views of Arctic politics may be even stronger than the “Literature Lobby” because of their far larger audience. A sample of recent Arctic news from the American media sources Fox, CNN, and Anchorage Daily News included 22 articles promoting a “race for resources” narrative and only one presenting a “responsible global governance” narrative.33) This coverage, considered misleading by Arctic experts, can undoubtedly shape public opinion and discourse in ways that will only encourage conflict and escalation in the Arctic.34)

Finally, and most importantly, robust connections exist between non-state actors, the Arctic, and broader global developments. To take the medieval analogy a step further, the Arctic can perhaps be seen as bellwether of neo-medievalism, where globalization and international trade cause the strength of states to fade compared to other actors on the international stage. This could lead to the dissociation between territorial sovereignty35) and political authority that characterized both mainland Europe in the medieval period and Svalbard in the early twentieth century.36) While the neo-medieval moment has not yet arrived and state actors are likely to maintain their dominance over Arctic governance for the time to come, it is undeniable that non-state actors have a significant and ever-evolving role to play in the future governance of the region.

Luke Campopiano is a senior history and philosophy student at the College of William & Mary in Virginia, USA. This article is a significant revision of my previous article “Non-state actors in the Arctic: Lessons from the 1920 Svalbard Treaty Negotiations” available at https://www.standrewshistorysoc.com/journal. I am grateful to the editors of the St Andrews Historical Journal for allowing me to reprint certain published material. I would also like to thank Andreas Østhagen and the two anonymous referees from The Arctic Institute for their helpful comments on previous drafts of this paper.

References