New Observers Queuing Up: Why the Arctic Council should expand - and expel

Senior Arctic Officials’ Meeting in Whitehorse in October 2013, Photo: Arctic Council Secretariat

When government representatives will gather for the 9th Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council in Iqaluit in the Canadian territory of Nunavut on 24 and 25 April this year, they will again have to decide on a number of applications by non-Arctic states, intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) and advocacy groups for the non-prestigious, though all the more sought-after status of observer in the Council. Greece, Turkey, Mongolia and Switzerland are reportedly among the applicants this year, together with the six non-state entities (the Association of Oil and Gas Producers, the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists, Greenpeace, the International Hydrographic Organization, Oceana, the OSPAR Commission, the World Meteorological Organization, and the European Union) that were left out in the cold at the last Ministerial Meeting in May 2013 in Swedish Kiruna. More interested parties may well follow suit.

If approved, the current list of 32 observers in the Council would be expanded considerably. However, there is little chance that this is going to happen, mainly due to a mixture of three factors: agenda overload, political discord about individual applications, and a general sense of hesitancy in widening the quantity of observers without having improved the quality of their commitment to the work of the Council first. The observer question has in the past been the primary focus of the media coverage of Ministerial Meetings, inside and outside the Arctic region.1) Yet, it has not necessarily been the primary focus of Ministers and state delegations themselves. This year’s Ministerial Meeting will see the Chairmanship of the Arctic Council handed over from Canada to the United States, which means first and foremost a lot will be talked about what has been achieved during the past two years and what shall be achieved in the next two years. The US has announced to set impacts of climate change in the Arctic, Arctic Ocean stewardship, and improving economic and living conditions for indigenous peoples as top priorities of their Chairmanship.2)

The topic of observer applications will occupy limited space on the two-day agenda in Iqaluit. Experiences of the last Ministerial Meeting in 2013 may also lower expectations for some applicants to be approved. In Kiruna, only state candidacies were discussed – and finally accepted – after hours-long and exhausting deliberations leaving little additional passion and time for non-state actors to be considered.3) When asked about the growing international attention in the work of the Council, member state delegations partly wonder about the degree of ever new observer applications, and are partly baffled what their role and rights are and should be. A certain degree of tiredness, even discomfort with the eternal observer question, is hard to ignore.

What adds to all this is that some applications are more contentious than others. For instance, Arctic Council member states have been reluctant to grant Greenpeace any access to Council meetings in the past, not even on an ad hoc basis. Many member states have serious reservations about the organization’s aims and means to protect the Arctic from any sort of offshore energy exploration and production entirely, which have in the past included protests on Gazprom’s Prirazlomnaya platform in the Pechora Sea in September 2013 and more recently against the Russian oil tanker ‘Mikhail Ulyanov’ in the ports of Rotterdam and Hamburg.4) Likewise, the application by the European Union is likely to be deferred a fourth time after 2009, 2011 and 2013, even though previous disputes with Canada about the EU’s import ban of commercial seal products have been resolved. Opposition is likely to come from Russia in response to Western economic sanctions imposed over the Ukraine crisis, which have for now thwarted a joint venture for exploratory drillings between ExxonMobil and Rosneft in the Kara Sea.5) The case of the EU remains a politicized issue in Arctic affairs, ignoring the many voices that see the EU as the one applicant being able to make a distinct contribution to Northern governance. For long, EU experts have participated regularly as temporary observers or invited guests, but this has become more complicated since the Arctic Council has in 2013 abandoned the flexible mechanism of granting ad hoc observer status in exchange for a more static list of criteria that conditions access to Council meetings.

Observers in the Arctic Council: Participation, not Status matters

From speculation to politics: No doubt, observers have a role to play in the Arctic Council. They can propose and partly fund new projects, disseminate information and contribute relevant expertise and input to subsidiary body meetings. That way, they contribute to the production of public goods like knowledge about the state and development of the Arctic environment. Observers further serve as multipliers for Arctic Council initiatives and can distribute results of environmental assessments and policy recommendations into the public sphere and other national and international venues with political authority. For a long time, the Arctic Council has actively sought involvement of ever more observers as ‘the work of the Arctic Council gains a global scale thanks to the wide range of its observers’.6)

The 2013 Minimata Convention to reduce mercury pollution worldwide is a case in point. Negotiations on the convention were informed by a longstanding cooperation between the Council’s Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), an observer to the Arctic Council since 1998, after the Arctic Council had in the 2000 Barrow Declaration called upon ‘the United Nations Environment Program to initiate a global assessment of mercury that could form the basis for appropriate international action in which the Arctic States would participate actively’.7) They pointed in joint reports to the adverse effects of mercury pollution on Arctic inhabitants and wildlife, and reinforced calls for an international treaty.8) Taken together, observers may help to make the Council more effective and raise its profile in international governance.

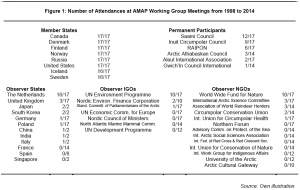

Apart from positive effects, a growing density of observer participants also has consequences on how the Arctic Council is run. Transaction costs of international cooperation in the Arctic increase, from bureaucratic and coordination costs in the Arctic Council Secretariat to the logistics and financial burdens of gathering in Working Groups, Task Forces and Expert Groups several times a year, in Senior Arctic Officials (SAO) Meetings biannually and in Ministerial Meetings every two years. As long as Arctic Council meetings take place in prestigious, symbolic, ‘truly Arctic’ places like Iqaluit, Nuuk, Inari or Tórshavn (and there is little indication member states tend to change this practice), ‘holding meetings in Arctic hamlets, as has been done in the past, becomes complicated – in fact, eye-wateringly expensive’.9) To tackle this problem, the Council has so far reacted with restrictions in the delegation size allowed to attend certain meetings. While there is indeed a lot of ‘hoopla around the new observers’,10) there is little talk about actual participation by observers and how they can help the Council to accomplish its goals. Not all actors theoretically eligible to attend also do so on all occasions. And one might argue that a non-attending observer does not cost a penny. And if some observers would attend some meetings of some subsidiary bodies on a regular basis, the benefits of their participation would fairly outweigh the costs. But the reality looks a lot different: If one takes a look into the meeting protocols of Arctic Council sessions, one will be puzzled to see that observers on average gather in Ministerial and SAO meetings where the only chance to have a say is in the corridors and coffee breaks. Only parts of the meetings are open to observers and in those discussions that are, the protocol forces them to literally ‘observe’. In many instances, there simply is not enough time to consult observer delegations. In Working Group meetings, however, where the Council member states ideally would like to see active participation by observers11) and where they in fact have the right to contribute and interact with member states and indigenous peoples’ organizations (Permanent Participants, PP), many observers seldom show up and those who do, attend very irregularly. Figure 1 below summarizes attendance rates among member states, Permanent Participants and observers (since granted status of PP and observer) for the case of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), which to some experts constitute ‘the core activity of Arctic cooperation’.12) This example is based on meeting protocols publicly available on the AMAP webpage and meant to be illustrative; it is not in all instances representative of general participation patterns. The Council has six Working Groups and most observers concentrate their expertise and resources in the work of one or two, with the notable exception of the almost omnipresent World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

There is no Permanency in Observer Status

Access to the Arctic Council is not of indeterminate duration once observer status has been granted. The status persists only as long as none of the Arctic states objects.13) Observers themselves further have to renew their interest in maintaining the status every four years, and will have their performance reviewed.14) Having said that, in its almost twenty-year history, the Arctic Council has to date never revoked an observer status. In the light of ever more interested parties willing to join the Council, it is high time for the Arctic Council to reconsider this practice.

The Council would be ill-advised to restrict observer status to certain actors already at the stage of application. The forum may lose authority and legitimacy as the primary institution for Arctic governance, if it applies its admission criteria inconsistently or if it continues its Kiruna approach of discriminating between different kinds of applicants.15) The Rules of Procedure are clear about which conditions have to be met for an interested actor to be considered a suitable candidate:

- accepts and supports the objectives of the Arctic Council defined in the Ottawa declaration;

- recognizes Arctic States’ sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the Arctic;

- recognizes that an extensive legal framework applies to the Arctic Ocean including, notably, the Law of the Sea, and that this framework provides a solid foundation for responsible management of this ocean;

- respects the values, interests, culture and traditions of Arctic indigenous peoples and other Arctic inhabitants;

- has demonstrated a political willingness as well as financial ability to contribute to the work of the Permanent Participants and other Arctic indigenous peoples;

- has demonstrated their Arctic interests and expertise relevant to the work of the Arctic Council; and

- has demonstrated a concrete interest and ability to support the work of the Arctic Council, including through partnerships with member states and Permanent Participants bringing Arctic concerns to global decision-making bodies.16)

As long as these criteria are fulfilled by new applicants, they all deserve a chance. Arctic Council member states cannot prima facie know whether, how and with which continuity observers will later contribute to Expert and Working Groups. Whether Turkey and Greece, for instance, are suitable candidates to demonstrate ‘their Arctic interests and expertise relevant to the work of the Arctic Council’ remains to be seen. Statement of interest is one thing, substantial commitment another. There are indeed good reasons to expand the list of observers, also at the upcoming Ministerial Meeting in Iqaluit. Yet, what is less understandable is the permanence with which established observers are waved through at Ministerial Meetings.

There should be no Permanency in Observer Status

One possible solution to the problem of a bloated Arctic Council is to validate the readmission of established observers more carefully. The yardstick for observers to keep their status should be past commitment based on rigid performance reviews carried out in regular intervals by the Working Group Chairmanships, with involvement of the Arctic Council Secretariat, and discussed by Senior Arctic Officials. Commitment would thereby mean the active and continuous contribution of scientific input, knowledge or material resources to at least one Working Group. Recommendations which observers to readmit for another period should then be forwarded to the Arctic states for approval at the next Ministerial Meeting. If the review reveals insufficient or irregular activity over a longer period of time, observer status should be suspended.

As Figure 1 indicates, several observers only exist on paper. This is true also when all six Working Groups are taken into account. A limited number of observers have over past years never or only sporadically attended any Working Group meeting. It is hence questionable whether they still fulfil the provisions laid out in the Rules of Procedure at all. In any case, their expulsion would come at little costs.

Quite the contrary, a stricter review system could have a number of positive ramifications. A systematic and coherent application of the Rules of Procedure would lend the Arctic Council more credibility in its policy towards international stakeholders. The threat of expulsion could also serve as an incentive to raise awareness among established observers which role they are able and willing to play in the body, which lays the groundwork for stepping up their efforts in contributing to Arctic Council governance. Finally, a review and reporting system would show prospective applicants that observer status in the Arctic Council has a price tag, and requires sustained interest, capacity and relevant expertise to contribute to Arctic science and knowledge production. As then-Norwegian foreign minister Espen Barth Eide put it crudely after six non-Arctic states were accredited in 2013, ‘there is no such thing as a free lunch’.17) As new applicants queue up, it may be the right time to demand more participation on behalf of the observers. And if necessary, to separate the wheat from the chaff.

References