Moving Mosaic: The Arctic Governance Debate

Small remnants of thicker, multiyear ice float with thinner, seasonal ice in the Beaufort Sea on Sept. 30, 2016. Photo: NASA

Espen Barth Eide seems to have reason to worry. Norway’s foreign minister recently spoke out in favor of admitting new observers to the Arctic Council in order to avoid “the danger of them forming their own club”.1) However, with the announcement of a new forum called the ‘Arctic Circle‘ is not to be confused with an existing New York artist and exhibition group called ‘The Arctic Circle’ in mid-April 2013,2) the rival club that Eide fearfully anticipated appears to have become a reality.

If the announcement of a rival club was a means to increase the pressure on the eight Arctic Council member states to admit new observers states, then it seems to have been a successful strategy. At the Council’s Ministerial Meeting in Kiruna on 15 May 2013, six new observer states were admitted, expanding the (so far entirely European) observer list by five key Asian states (China, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore), and one European country – Italy. The total number of observer states was thus raised to 12 and the number of observer non-governmental organisations kept at 11.3)

Despite the extension of the observer list, the Arctic Circle is in the world now, and so the question arises: Will this new forum take clout and political relevance away from the established political forum for the region, the Arctic Council? Unfortunately, the debate about the effect of the new institution on Arctic governance too often takes a zero-sum game approach, taking place within the narrow margins of a rivalry concept, which gives short shrift to the complex issue of Arctic governance.

The Arctic Governance Mosaic

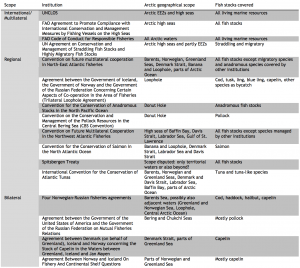

The Arctic governance system is already characterized by a multitude of different governance arrangements. This constellation includes bilateral, regional and multilateral/international institutions and regimes. The Arctic Council is but one piece of this colorful mosaic.4) While many writings on Arctic governance often mention only the Arctic Council and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as relevant Arctic institutions, there exist a multitude of organizations, conventions, and agreements on various levels. To take Arctic fishing as an example, the table below outlines the numerous institutions with rules and regulations for Arctic fishing activities, ranging from broad, multilateral institutions on the UN (especially on the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO)) level to the numerous regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) and bilateral agreements.

This is not to say that the Arctic fishing regime is perfect, requiring neither improvement nor reform. Not all relevant fishing actors are party to all relevant institutions; not all species are covered in all maritime areas; and especially the multilateral institutions with relevance for the high seas areas of the Arctic Ocean struggle in several ways with severe implementation and compliance issues. The recent initiative to debate a RFMO for the high Arctic Ocean5) is indicative of the current shortcomings of the significantly fragmented Arctic fishing regime. Nevertheless, beyond the High Arctic Ocean, a regional approach to fisheries management makes sense. This is so because of the differences in climatic conditions, fisheries environments and species and stock distributions around the Arctic, as well as the varying importance of fishing regions for different fishing actors. The notable number of existing RFMOs mirrors this.

Existing institutions, new arrangements such as the Arctic Circle, and institutional changes such as the acceptance of new observer states to the Arctic Council must all be carefully analysed to assess their actual substantive meaning for policies and their effect on peoples’ livelihoods, the state of the environment, and the state of fish stocks, among others. All other talk, especially about one institution ‘stealing’ clout from another, remains shallow if it fails to address the actual issues at stake.

The Arctic Circle: The New Kid on the Block?

Against this background, what does the creation of the Arctic Circle mean for Arctic governance generally and the Arctic Council specifically? Any talk of competition between the Arctic Circle and the Arctic Council must first of all consider the desired spoils of any such competition. These might include pre-eminence in particular issue areas, funding, or political attention. Such a competition might also inadvertently cause redundant work on the part of the two organizations and, accordingly, a waste of resources which could have been avoided had the institutions joined forces, shared burdens, and exploited their synergies where applicable.

First of all, the Council is meant to be a policy forum predominantly for the eight Arctic states with the consultation of the Permanent Participants and the possible contribution of observer states and organisations to the working groups. Even with the admission of new observers, the Council keeps the principle of exclusiveness when it comes to its membership. Further, the Council is currently developing more and more into an umbrella institution for the eight Arctic countries to negotiate legal arrangements among them.

Second, one has to remember that the main purpose and biggest merit of the Arctic Council is to enhance Arctic research, which it does with tremendously detailed and sophisticated reports. At the recent Ministerial Meeting new extensive research reports were added to the already very impressive list of research reports from the Council, such as the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment, “the first Arctic-wide comprehensive assessment of status and emerging trends in Arctic biodiversity”,6) the Arctic Ocean Acidification assessment, the Arctic Ocean Review report, the report on Ecosystem Based Management, and reports from the Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic initiative.

The Arctic Circle, in fact, will work to be and do something different from the Arctic Council, at least as far as one can tell from today’s available information about it five months before its official inauguration.

First, the Arctic Circle is designed as a non-profit organisation and not as a political forum primarily for states. It does not intend to provide a forum for state negotiations to produce legally binding arrangements. On the contrary, it has a very inclusive approach to actor involvement, aiming to be a “forum for discussions” and generally an umbrella organisation for “as many Arctic and international partners as possible,” including “a range of Arctic and global decision-makers from all sectors, including political and business leaders, indigenous representatives, nongovernmental and environmental representatives, policy and thought leaders, scientists, experts, activists, students and media”.7)

Second, while the forum aims to organize “sessions” on “global research cooperation”, there are no explicit research tasks outlined that the institution would adopt and implement on its own.

These fundamental differences illustrate that it makes little sense to talk of a rivalry between the Arctic Council and the Arctic Circle, at least from today’s knowledge of what the Arctic Circle is intended to be. If the Arctic Council loses clout, it will first and foremost depend on the political attention its members devote to it – in terms of actual usage as a forum, research efforts, national representation on ministerial meetings, funding, administrative endowment –and not on the decision by, for example, China, Iceland, and Google to discuss their involvement in the Arctic in a conference or business-like fashion on a regular basis.

At the moment, it looks like the opposite development in fact: the Arctic Council appears to gain in importance and the institution shows more activity than ever before, quite independent of the fuss about the admittance of new observers.

Two binding agreements have been negotiated under the auspices of the Council: the 2011 Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic and the 2013 Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic. The Kiruna meeting also saw the establishment of a Task Force to develop an Arctic Council action plan or other arrangement on oil pollution prevention, which will report at the next Ministerial Meeting in 2015.8)

A considerable number of further initiatives have been announced in Kiruna, showing a highly active Arctic Council. Several Task Forces have been created; one to facilitate the creation of a circumpolar business forum; one to develop “arrangements on actions” to reduce black carbon and methane emissions in the Arctic; and one to work towards an arrangement on improved scientific research cooperation among the eight Arctic States.

Recommendations are planned to integrate traditional and local knowledge in the work of the Arctic Council. The Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) will work on recommendations to increase awareness regionally and globally on traditional ways of life of the Arctic indigenous peoples and will present a report on this work at the next Ministerial meeting in 2015. The SAOs will further develop a plan to ensure the implementation of the recommendations from the new Arctic Biodiversity Assessment, which was presented in Kiruna, and present a progress report at the next meeting.

The Council has also been strengthened institutionally and politically. At the Ministerial Meeting in Nuuk in 2011, a standing Arctic Council secretariat was established in Tromsø. The Council’s prominence was further raised as Secretary of State John Kerry attended the 2013 Ministerial meeting, marking only the second time that the U.S. administration sent its highest-ranking cabinet member to the biannual meeting.

The member states have also been active in clarifying the different participation categories of the Council. Specifically, the role and admittance of observers has been institutionalised at the 2013 meeting with updated Rules of Procedure and an Observer Manual, which outlined the conditions, rights and duties of prospective and current observers.9) Crucially, “[t]he primary role of observers is to observe the work of the Arctic Council. Furthermore, observers are encouraged to continue to make relevant contributions through their engagement primarily at the level of working groups”.10)

For clarification, many commentators speak of the category of ‘permanent observers’, which has just been extended. This term has been used to differentiate from ‘ad hoc’ observer status, which for example China and the EU had in the past. However, one has to clarify that the official Arctic documents nowhere use the term ‘permanent’ and thus this category has no official and legal relevance. The term can also be quite misleading, as current and newly admitted observers can have their status revoked. As the Manual reads:

“Observer status continues for such time as consensus exists among Ministers. Any observer that engages in activities which are at odds with the Ottawa Declaration or with the Rules of Procedure will have its status as an observer suspended”.11)

Finally, there is no automatic right to attend all Arctic Council meetings or access all related documents once observer status has been granted:

“Observers may attend meetings and other activities of the Arctic Council, unless Senior Arctic Officials have decided otherwise. The Heads of Delegation of the Arctic States may also at any time meet privately at their discretion […] Observers admitted to a meeting will have access to the documents available to Arctic States and Permanent Participant delegations, with the exception of documents designated as ”restricted to Arctic States and Permanent Participants””.12)

The substantive influence of observers is also limited. They have to propose projects through an Arctic State or a Permanent Participant and “the total financial contributions from all observers to any given project may not exceed the financing from Arctic States, unless otherwise decided by the Senior Arctic Officials”.13)

Observers also have to continuously prove their ability and willingness to actively and constructively contribute to the work of the Arctic Council; they must be accredited before each Ministerial Meeting:

“Observers are requested to submit to the Chairmanship not later than 120 days before a Ministerial meeting, up to date information about relevant activities and their contributions to the work of the Arctic Council should they wish to continue as an observer to the Council.”14)

Institutional Rivalry? Think Again

In conclusion, against the background of the strengthening and opening of the Arctic Council to new observers and the different portfolios of the Arctic Council and Arctic Circle, it makes more sense to understand the Arctic Circle as an addition of another piece to the Arctic governance mosaic instead of a rival to the Arctic Council. This new piece will have to find its place and purpose among the many different institutions that already exist with relevance for the Arctic, and it should be evaluated according to the merit and added value it brings, especially for the people living in the region. This will, not least, also depend on how the new forum will be perceived by the eight Arctic states. As the above analysis outlines, there is little reason to expect rivalry with the Arctic Council given the substantial differences between the two institutions in terms of scope, membership outreach, and legal outcomes. Espen Barth Eide can thus put his mind at ease.

References