Looking Up: Women in Arctic Science

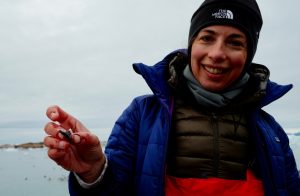

Dr. Kristin Laidre (left) and Malene Simon (right) examine a time-lapse camera installed to photograph narwhals and the glacial environment in northwestern Greenland. Photo: Twila Moon

In recent years, women researchers, scientists, and local champions have elevated their visibility and empowered their voices across the world. The Arctic is no exception. With powerful organizations like 500 Women Scientists and local movements like Women in Polar Science and Plan A growing their reach and impact, women are sharing their personal narratives, highlighting their contributions, and supporting each other like never before. The Arctic Institute’s Breaking the Arctic’s Ice Ceiling is our team’s contribution to this movement. In a series of commentaries, articles, and multimedia posts, we are highlighting the work of women working and living in the Arctic.

The Arctic Institute Breaking the Arctic's Ice Ceiling Series 2019

- Looking Up: Women in Arctic Science

- The Gender Gap in Arctic Research Awards and Leadership – Infographic

- An Arctic Imposter’s Journey to Belong

- Women Are America’s Climate Change Champions

- Vegan at Sea-gan: The Arctic Ocean

- Golden Rule in Arctic Science and Community Partnerships

- Is the Future of the European Arctic Socially Sustainable?

- Geo-mapping in the Canadian Arctic

- Women in Polar Research: A Brief History

- It’s Our Table: Indigenous People Shaping Arctic Policy

On a recent field expedition to Greenland , it was common to hear: Ask Kristin about narwhals. Ask Malene about the monitoring instruments. Ask Ian about ocean temperatures. Ask Beth about seabirds. Ask Twila about the glacier ice. To me, this is the sound of progress in women’s Arctic science participation: four of the five expedition scientists were women, and we (mostly) didn’t bat an eye at that statistic. Active in my field, glaciology, for 15 years, I have witnessed a remarkable expansion in the participation and prominence of women in Arctic research.

Growing up as an athletic tomboy who liked math and science, I was used to being one of only a few females in any given group. As an undergraduate, I was, for the most part, blissfully unaware of gender discrimination. Headstrong, I was always bold enough to invite myself to the table.

Things began to change in graduate school as I learned more about systemic discrimination against women and the cumulative injustice of micro-aggressions and unconscious bias. I was also searching for new role models—“who I want to be when I grew up”—and coming up short. I knew only a small handful of senior female scientists, like Robin Bell and Helen Fricker, but saw few in my day to day research. A couple of years into my studies, I decided to step out of my PhD program to pursue other work, in part because I was still missing these career role models. Over the course of two years, however, I came to realise that I dearly missed science.

Returning to graduate school, I brought a new personal awareness on gender equity and an eagerness to connect as a mentor and mentee. From this perspective, I could more clearly see the surge in women in Arctic science. I talked regularly with LuAnne Thompson, a physical oceanographer, and took a class she co-taught with Cecilia Bitz, a sea ice and climate scientist.

Glaciology also had a growing proportion of women scientists working their way up the ranks. Students who were senior during my first go at graduate work were now in tenure track and research scientist positions—I could see Michele Koppes leading science at the University of British Columbia and Erin Pettit balancing research and a successful education program, Girls on Ice (now Inspiring Girls Expeditions), at the University of Alaska. I could find successful women scientists at the helm of almost every project and program type. Connecting and contributing to this growing community gave—and continues to give me—many examples of women I would like to be when I grow up. Knowing this gives me an extra boost of confidence in my work, my abilities, and my future.

So, have we made it? Is the work complete? No. We should celebrate progress, but there are also many areas for continued effort. The biggest strides in progress will come via effort and self-awareness by both women and men. We must work individually and collectively to:

- Recognise women for their achievements; women continue to be underrepresented in awards and fellowships.

- Change the culture that has allowed the offences behind the #MeToo movement to systematically develop and be covered up for so long. Identify and weed out habits, language, and work culture elements that do not support broad success across genders (and other underrepresented groups).

- Evaluate projects for gender equity and strive to include a diversity of participants.

- Recognise and speak up about sexual harassment while building trusting and professional work environments.

- Recognise the differences among people; account for differences in background, opportunity, and support; and educate women and men on available resources and the critical importance of being attentive to this issue.

- Introduce female junior scientists and researchers to female colleagues—act as a connector.

- Write recommendation letters that avoid common gender biases.

- Spotlight women who can serve as role models, colleagues, mentors, and supporters.

If you are a woman, you can also plug into organizations like 500 Women Scientists, MPOWIR, and the Earth Science Women’s Network, which provide mentoring opportunities and resources. Early on, I sought support. Now, I can also provide support.

The benefits of this ongoing work are many. New research ideas from diverse perspectives, higher confidence among women across career levels, more equitable work opportunities, and more supportive work environments. The increasing visibility of women Arctic researchers is opening up new pathways and new audiences to Arctic science. Let us celebrate current successes, and use them to bolster our collective energies to continue forward progress.

Dr. Twila Moon is a Research Scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, which is a center of the University of Colorado Boulder Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, and co-founder of the nonprofit Wheelhouse Institute.