Investigating the Barriers to Building Climate Adaptation of Cultural and Natural Heritage Sites in Polar Regions

An inuksuk or inukshuk monument is a symbol of Inuit culture in the Arctic. Photo: Lee Coursey

Cultural and natural landscapes of the polar regions (Arctic and Antarctic) are threatened by the effects of climate change combined with human-induced influences such as tourism, shipping, oil and gas explorations and developments. Thawing permafrost, induced by global warming, triggers changes in ice sheets and glaciers, snow cover, floods, erosion, and sea-level rise are some of the effects of climate change in the polar regions. The implications of these rapid changes have caused disruption of socio-economic activities1) such as fisheries, agricultural activities, and livelihoods and loss of “the common heritage” of both polar regions.2)

The Arctic and Antarctic share a rich legacy of history of humankind and nature. While the Antarctic stands isolated, the Arctic and its unique heritage have been exposed to the hazards from global industrial, administrative, and technological developments in polar region.3) Polar regions are rich in terms of cultural (archaeological sites, objects, former industrial sites, historic mining sites,4) timber buildings), natural (marine biodiversity, mountains, glaciers), and intangible heritage (hunting activities,5) fishing,6) Indigenous languages, biocultural heritage, and spiritual practices). However, polar heritage is being eradicated because of abandonment, loss of traditions and settlements, extinction of Indigenous languages,7) crop failures, and over-tourism.

Only a small number of studies have reviewed the effects of climate change on cultural heritage in polar regions.8) Although scholars systematically reviewed the barriers in climate adaptation of heritage,9) there is still a gap to fill in the context of polar regions. This commentary presents the main barriers in climate adaptation of cultural and natural heritage10) in the Northern and Southern polar regions, that derive from the publications for the period of 2002-2020.

Main Barriers to Building Climate Adaptation of Polar Heritage

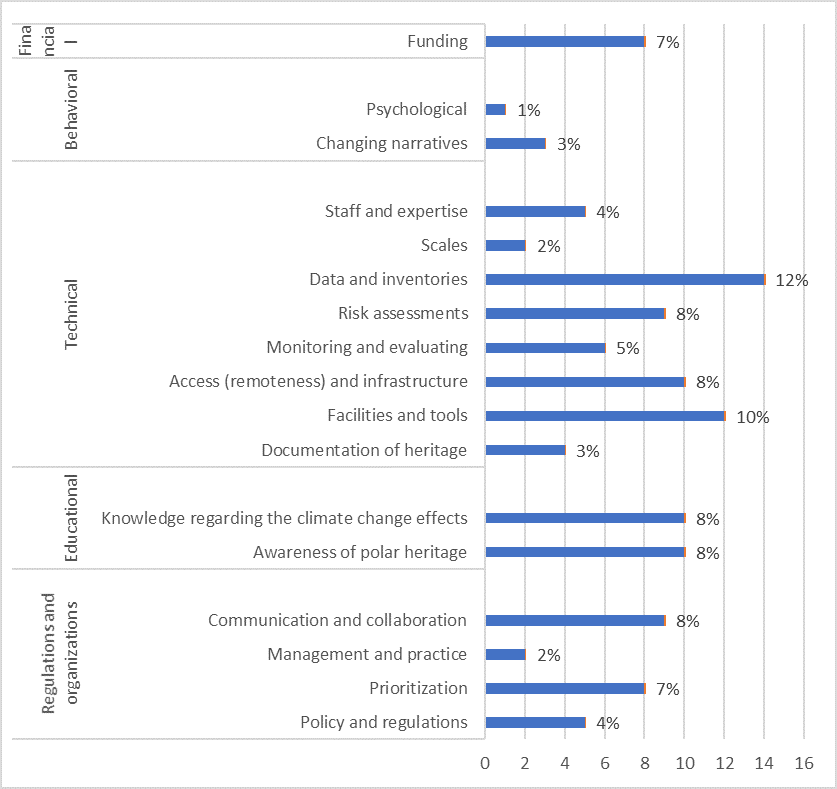

Five main barriers were identified, including (1) technical barriers, (2) regulations and organizations, (3) educational, (4) financial, and (5) behavioral barriers (see the figure below).

Technical Barriers

Data and inventories, the most mentioned technological barrier, refers to the challenges in the mapping and completing inventories of maritime heritage. Limited data on permafrost has hindered the development of a coastal vulnerability index for Alaska11) Following that, strong concerns were raised regarding the facilities and tools, which refers to the lack of methodologies, inadequate climate change projections and models12) used in climate adaptation of cultural heritage.

Accessibility and infrastructure is major constraint in the Arctic and Antarctic contexts due to their remoteness and harsh environmental conditions. It causes problems in moving researchers, staff, and collections,13) especially in the case of the High Arctic. Moreover, there are inadequate risk assessments of sites including the parameters for erosion, permafrost thaw, vegetation increase, and human access14) Little known about the current state of heritage sites in the polar regions, there is an increasing emphasis on the need to monitoring and evaluating the level of the impacts of climate change on cultural heritage sites in the Arctic.

Northern communities are particularly struggling in the documentation of at-risk sites, which often omits the significance of the site with the extent of the damage induced by climate change. Lack of staff and expertise together with insufficient funding can impede the preservation of archaeological sites, which are at the risk of disappearing due to climate change.15) The issue of scales still exists in bridging the knowledge between small-scale studies and greater scale work in national policymaking.

Regulations and Organizations

A bottom-up approach is encouraged for better communication and collaboration in the projects between archaeologists and indigenous and local communities (Hillerdal C, Knecht R & Jones W (2019) Nunalleq: Archaeology, climate change, and community engagement in a Yup’ik village. Arctic Anthropology 56: 4-17.)) In the case of Tr’ondëk Hwëch of Yukon Territory, the documentation, transcription of narratives, and digitization can allow access to the local environmental knowledge of the past to tackle the present issues.16) As the degree of degradation of the site differs greatly, there is a need to identify and rank vulnerable sites to help focus the use of resources on the prioritization of these sites.17)

Policy and regulation includes the inconsistent, late, and inadequate enforcements in taking protective actions. In the context of flood risks, absence of flood risk governance, policies, and measures lead to inability to reduce impacts.18) In a few instances, management and practices is mentioned as a barrier to the climate adaptation of cultural heritage sites. National parties of the Antarctic Special Protected Areas (ASPAs) should provide feedback for the improvement of the management plans of these sites.19)

Educational Barriers

Awareness of polar heritage can be increased through virtual exhibits throughout Arctic and Antarctic regions,20) as physical visits are limited. Another significant educational barrier is knowledge regarding climate change effects, which refers to the integrated knowledge of changing climatic conditions and deterioration processes.21) The experience and knowledge about the indicators of climate change effects is limited, as well as the consequences of it on sites.22)

Financial Barriers

Financial barriers are the second to least common barrier, which reflects constraints in funding of climate adaptation projects of cultural heritage. The agencies have limited budgets and staff to carry out the projects within tight deadlines23) in the polar regions.

Behavioral Barriers

Behavioral barriers, that are categorized as changing narratives and psychology, have not been as influential as other barriers in climate adaptation of polar heritage. The interpretation of historic sites requires the construction of narratives of cultural heritage and environmental concerns. However, it is sometimes impeded by language barriers. To give an example, the circle dance of ohuokhai which is practised by Sakha, Turkic-speaking people in northeastern Siberia in Russia, is threatened by a steadily declining language in industrialization, globalization, and climate change in the future.24) Dislocated from their lands, indigenous people are distanced from their lands, cultural practices, and heritage. However, psychology has gained little attention in the reviewed publications as a barrier to building climate adaptation of polar heritage.

Conclusion

The barriers to climate adaptation are rarely examined particularly in the context of cultural and natural heritage resources in the polar regions. Realizing the potentials of investigating such barriers can encourage contributions to polar studies. Considering the large scale of indigenous communities residing in these regions, the climate adaptation of heritage sites is needed, including archaeological sites, water resources, national parks as well as intangible heritage such as indigenous languages. The aforementioned barriers are often interconnected and influence each other. To give an example, data and inventories cannot be isolated from facilities and tools as they refer to the technologies to implement them. Similarly, across barriers, awareness of polar heritage as an educational barrier and prioritization as an organizational barrier appear to have the same weight as constraining elements. Prioritization of polar heritage sites relies on the understanding of their cultural and historical significance. Thus, it is significant to interpret the interconnection between these challenges to overcome barriers and enable climate adaptation of polar heritage.

Gül Aktürk was a Visiting Fellow with The Arctic Institute in 2021. She is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Architecture at TU Delft in the Netherlands.

References