Can International Law Protect the Arctic from Oil Spills?

Setting out a skimmer during a spill response exercise in Kirkenes, Norway. Photo: Arctic Council Secretariat

Offshore oil development in the Arctic is still in its nascent phase, with production occurring in Russia and Norway, but on hold in Canada, the US, and Greenland. As production rates and new discoveries are expected to increase in the coming years, so will the risks of a large-scale oil spill in Arctic waters. The challenging operating conditions, lack of infrastructure, and effective clean-up techniques in Arctic conditions exacerbate the need to ensure robust regulation of petroleum activities in the region. International law provides a detailed framework regulating spills from shipping, but is not nearly as stringent when it comes to spills from petroleum development activities. While international treaties establish binding obligations to cooperate in response operations, there is a gap in regulating the prevention of such oil spills. The role of non-binding regulation, or soft law, is growing, with the Arctic Council leading the way.

What is the difference between prevention and response to upstream accidents?

The biggest risk to Arctic marine environments is arguably posed by a possible large-scale oil spill,1) which typically occurs either from a tanker spill or from loss of well control when ‘formation pressure exceeds the pressure applied to it by the drilling column of drilling fluid’.2) Whereas in shipping accidents, the maximum amount of oil that might escape is easily known, with well blowouts, the oil might gush into the ocean for months until the well is capped. A blowout can be caused by a pocket of oil under high pressure, human error, a technical failure, or a combination of all of the above.3)

While shipping is extensively regulated in international law, mainly under the agenda of the International Maritime Organisation, upstream petroleum accidents are not equally covered by international regulation.4) But well blowouts are responsible for the biggest oil spills resulting from offshore petroleum development activities, such as the Deepwater Horizon or, closer to the Arctic, the Ekofisk Bravo in Norway.

Most measures directed at minimising the risk to human health and the environment can be divided into prevention and response. Prevention measures are designed to avoid an incident before it happens, while response operations are aimed at containing the spill and recovering as much oil as possible. While it is important to have robust response systems in place, the analyses of the previous blowouts, such as Deepwater Horizon in the US Gulf of Mexico and Montara in the Timor Sea off Australia’s coast, demonstrate that failures at the prevention stage were among the root causes of the incidents.5)

Prevention measures include requirements for materials, design, and processes in the construction and operation of a well, including safety management systems. Arctic conditions warrant additional prevention requirements as they might compromise the performance of certain materials and processes. For example, the cement used for sealing the wellborn might freeze before establishing sufficient compressive strength.6)

Safety management systems (SMS) are a crucial element of oil spill prevention and were identified as culprits in both Deepwater Horizon and the Montara blowouts. The SMS vary between operators but all contain basic elements such as hazard analysis, training, investigation of incidents, auditing, reporting, and safe work practices.7) Arctic conditions warrant additional requirements to be adopted for the training of personnel working in extreme weather conditions and limited/extensive daylight.8)

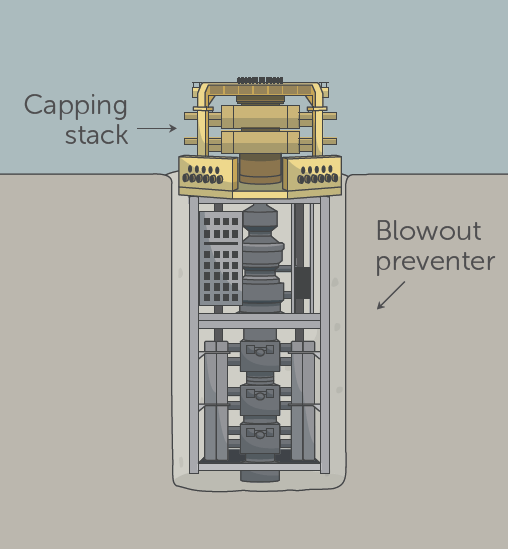

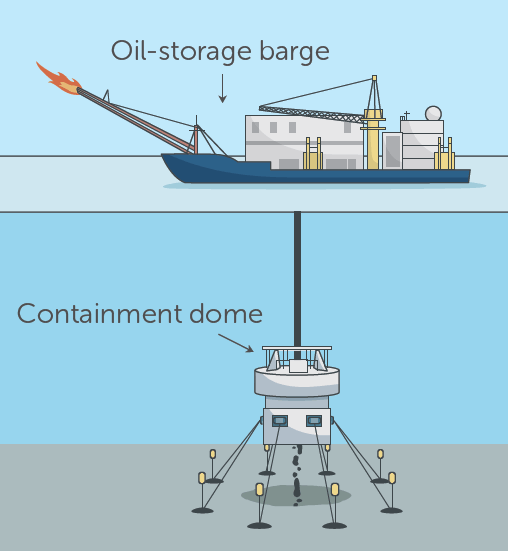

After a blowout, the priority is to regain control of the well as soon as possible to stop the flow of oil. However, it can take months to “kill” a well (e.g. over five months for Deepwater Horizon). External equipment, such as capping stacks and containment domes (see images below), can be used to stop or divert the oil release. In Arctic conditions, the deployment of such equipment is more challenging due to the lack of natural light, low temperatures, lack of infrastructure capabilities, and potentially challenging subsurface conditions. This external equipment is used to restore well control, but is nonetheless considered a temporary fix until the well can be permanently controlled.9)

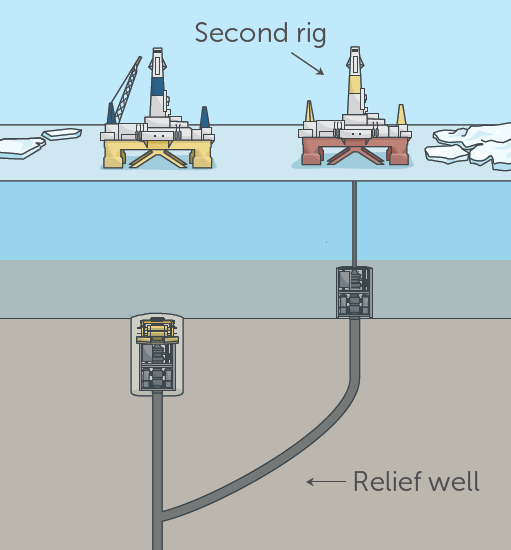

To permanently control the incident well, a relief well needs to be drilled to stabilise the pressure (see image above). In the Arctic, one of the biggest concerns is an end-of-season blowout, which would require response operations to be conducted in the presence of autumn and winter ice. For this reason, some jurisdictions, including Canada, Norway, and Greenland, require that companies demonstrate the capability to drill a relief well during the same drilling season with a stand-by rig.

If an oil spill has occurred, the operators and the state response systems come into play to clean-up as much oil as possible. Site-specific response plans typically list the plan of response actions, equipment and techniques for recovery and containment of a spill. The Deepwater Horizon inquiry found that the BP response plan was in parts copied from other materials and considered effects on walruses, non-existent in the Gulf.10) In Arctic conditions, response operations might be challenging due to the short duration of the ice-free season, lack of infrastructure, and lack of proven methods of oil spill clean-up in Arctic conditions.11) An effective response requires coordination and exercises between industry actors and local authorities. Sometimes the resources available to the operator are not enough to effectively tackle a spill. Exercises, including international ones, are essential to ensure that such cooperation and communication methods, including immigration and customs regulations, are effective. One of the issues revealed by the Deepwater Horizon investigation was the rejection of some international offers of assistance due to legislation in place preventing foreign vessels from participating in trade between US ports.

Due to the difficulties in response, and to minimise the risk to human health and the environment, prevention of oil spills should be addressed effectively by regional and international regulation. So how do international treaties regulate oil spills in the Arctic?

Treaty regulation of Arctic oil spills: response over prevention

Offshore oil development is generally not a subject states are eager to regulate at an international level.12) While many have called for an ‘Arctic Treaty’,13) currently the following agreements apply to the prevention and response to oil spills in the Arctic: the International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC), the Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution, Preparedness and Response in the Arctic (MOSPA), and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The UNCLOS is the most comprehensive treaty regulating maritime areas. While it lays down a number of fundamental provisions relating to states’ duties to protect and preserve the marine environment, it relies on further global and regional cooperation and international organisations to formulate rules, standards, and practices. Although this ensures the relevance of the regulation, it might also lead to ambiguity regarding which standards are to be generally accepted,14) particularly in the Arctic regional context. Further, rules and standards exist for shipping,15) but not for upstream petroleum activities, which limits the applicability of the relevant UNCLOS provisions.

The OPRC is a global treaty regulating pollution from both ships and offshore oil installations. The MOSPA is a specialised Arctic agreement negotiated and adopted under the auspices of the Arctic Council. Although together both create a strong framework for cooperation post-spill, neither focuses on preventing accidents or addressing Arctic-specific response problems, such as the lack of infrastructure.

The OPRC does not set requirements for the design of the well, pipelines, installations, or safety management. Instead, it places obligations on cooperation in response operations after the spill occurs. It requires that operators and states plan for emergencies and establish plans and response systems. Under the OPRC, states must establish: a minimum level of prepositioned oil spill combating equipment; a programme for exercises and training; detailed plans and communication capabilities for responding; and a relevant coordination mechanism. Although the requirement to have such equipment available is written into the legislation of Arctic coastal states,16) the proximity of such equipment to drilling sites, its transportation in bad weather, and effectiveness are questionable. For example, in the US, the nearest permanent Coast Guard air base to the Arctic coast is in Kodiak, Alaska, some 900 miles away from Point Barrow, the northernmost point of Alaska.17)

In relation to international cooperation, the OPRC requires states to report any incidents, cooperate, and provide advice, technical support, and equipment for the purposes of oil spill response. It encourages states to adopt further bilateral and regional treaties, and in the Arctic, a decision was made to negotiate such a region-specific ‘marine oil pollution response instrument’18) – the MOSPA.

Despite being an Arctic-specific treaty, the MOSPA does little to address the prevention of oil spills or the response challenges. Most of the Agreement’s provisions repeat the OPRC’s requirements for equipment and exercise, communication plans, and coordination mechanism, national response system, incident notification, assistance requests and movement of resources across borders almost verbatim. The MOSPA’s added value mostly stems from its association with the Arctic Council’s institutional capacity to monitor and facilitate the implementation. Its new obligations, compared to the OPRC, are few and relate to monitoring, review of joint operations, and extension of the geographical scope to the areas beyond national jurisdiction. This is significant considering the lack of protection available for such areas in general under international law.

The MOSPA establishes regular meetings to review the implementation, which is conducted through the Arctic Council Working Group (EPPR). Under the Agreement’s framework, exercises are regularly conducted around the Arctic, the latest round took place in March 2018 in Finland.19) The MOSPA includes non-binding Operational Guidelines providing forms for request for and provision of assistance, recommendations, and information on the national organisation of the response system for each of the Arctic States. The EPPR adopted a revision procedure to keep the Guidelines up to date.20)

The response plans for Arctic offshore oil development, although present in every jurisdiction in compliance with the OPRC and the MOSPA, have been heavily criticised by environmental NGOs. For example, Shell’s Oil Spill Response Plan for the Chukchi Sea has been approved by the regulator, but was met with criticism from the environmental NGOs for making unrealistic assumptions regarding the success rates of mechanical recovery.21) These concerns were reiterated by Shell’s shortcomings during the 2012 drilling season, when the containment dome failed and was crushed during testing, and when the drilling rig Kulluk ran aground in a storm, leaving the crew to be rescued by the Coast Guard.22)

Although the treaties discussed here are significant for the protection of the Arctic waters, they are not sufficient to improve safety at offshore petroleum installations and to ensure the prevention of a large-scale oil spill. The lack of common prevention and well control standards is a clear gap in the treaty-based regulation of the Arctic offshore petroleum development. Furthermore, although treaties address preparedness and response in general, they do not sufficiently address Arctic-specific challenges, such as the lack of consideration of effective oil clean-up techniques and development of spill response infrastructure along the Arctic coasts. Could the non-binding regulations of the Arctic Council possibly bridge the regulatory gap?

Soft law regulation of Arctic oil spills

Non-binding guidelines and standards play an important role in environmental and safety regulation of offshore petroleum. The Arctic Council has been active in research and cooperation in prevention of and response to oil spills in the Arctic. Despite its inability to make binding decisions, it has initiated research and cooperation, and produced some non-binding normative outputs, such as the 2009 Arctic Offshore Oil and Gas Guidelines.

The Guidelines address oil spill prevention, preparedness, and response and are complementary to existing treaties. For example, Section 6 of the Guidelines engages with well control requirements and refers to Arctic conditions. It requires that blowout preventers, drilling fluids, casing, and cement be ‘suited to Arctic conditions including moving ice and possible subsurface permafrost’.

Emergency preparedness and response are addressed in Section 7 of the Guidelines, which offers some Arctic-specific provisions, absent from both the OPRC and the MOSPA. For example, the Guidelines require an ice-management plan in addition to the usual emergency response documents, and the consideration of alternative clean-up techniques suitable for Arctic conditions.

Finally, emergency response plans are expected to contain information on ‘precautionary measures to secure the well’ such as the relief well arrangements, with the demonstration of the availability of necessary equipment and support systems.

The Guidelines comprise the most comprehensive soft law document on offshore petroleum in the Arctic. However, some commentators remain sceptical about their overall effectiveness due to their non-binding nature, and the lack of a ‘regular evaluations procedure’.23) The Guidelines are featured in the national legislation of Arctic States, such as the 2016 US Arctic Drilling rule24) and Greenland.25) Studies considered their implementation in Canada, the US, Greenland, and Russia.26)

In 2014, PAME issued a new guidance document on Safety Management and Culture in the offshore industry. These Safety Guidelines make recommendations for regulators to ‘define and communicate expectations regarding positive safety culture’, and to require operators to ‘establish, implement, and improve their safety culture’. They further identify challenges and recommended approaches for improving safety management. Given the significant role safety management plays in preventing accidents, this is an important development.

Another Arctic Council tool in combating oil spills is the Framework Plan on Oil Pollution Prevention (2015). The majority of the Plan’s provisions relate to ‘sharing lessons learned and best practices’ and exchange of data. The Plan recommends the promotion of cooperation between competent national authorities and facilitated the compilation of two knowledge-gathering reports on measures designed to prevent accidents and the use of standards in Arctic offshore petroleum activities. To facilitate the implementation of the Plan, the Arctic Offshore Regulators Forum has been established in 2016. The Forum brings together the offshore petroleum safety regulators across Arctic States and holds meetings twice a year to exchange information, best practices, and relevant experiences learned from regulatory efforts.

Since its establishment, the Arctic Council has consistently worked on oil spill prevention and response. In terms of scope, its outputs are wider than those of treaties’. Unlike treaties, they address oil spill prevention measures, well control, and Arctic-specific responses. These are positive considerations but they come with some trade-offs. The provisions of the non-binding documents are largely not formulated as international legal rules. Rather than placing obligations directly on Arctic States, the Council’s documents typically establish the review of best practices and make recommendations to the relevant regulatory bodies, the industry, and other relevant stakeholders. Then again, an important advantage of the Arctic Council’s outputs on oil spill prevention and response is the way it involves relevant non-state actors: national and regional government agencies and industry stakeholders.

Conclusions

The importance of a robust regulatory framework for offshore safety in the Arctic is hard to overestimate. Both prevention and response measures for oil spills from shipping are regulated under the global IMO agenda, whereas in the case of spills from blowouts, it is only the response measures that fall under the scope of treaty regulation. The increasing role of soft law governance should be acknowledged, especially where the norms and standards are constantly evolving and require the involvement of a number of non-state stakeholders. In the Arctic, the Arctic Council and its working groups have now fully asserted their position as the regional governance and knowledge centre on oil spill prevention and response. However, recommendations are not obligations. Even if there is some incentive for relevant parties to comply, the fact that the obligations are not legally enforceable means that if often remains up to commercial entities to make the right decision.

Dr Daria Shapovalova is a lecturer in law at the University of Aberdeen. The text is based on the forthcoming article ‘International Governance of Oil Spills from Upstream Petroleum Activities in the Arctic: Response over Prevention?’ International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 34 (2019) pp. 1-30. The author thanks Dr. Roger Norum and The Arctic Institute team for their editing and review efforts.

References