Geo-mapping in the Canadian Arctic

The Geological Survey of Canada’s GEM fly camp along the Natkusiak volcanic succession, July 2010. Photo: Marie-Claude Williamson

In recent years, women researchers, scientists, and local champions have elevated their visibility and empowered their voices across the world. The Arctic is no exception. With powerful organizations like 500 Women Scientists and local movements like Women in Polar Science and Plan A growing their reach and impact, women are sharing their personal narratives, highlighting their contributions, and supporting each other like never before. The Arctic Institute’s Breaking the Arctic’s Ice Ceiling is our team’s contribution to this movement. In a series of commentaries, articles, and multimedia posts, we are highlighting the work of women working and living in the Arctic.

The Arctic Institute Breaking the Arctic's Ice Ceiling Series 2019

- Looking Up: Women in Arctic Science

- The Gender Gap in Arctic Research Awards and Leadership – Infographic

- An Arctic Imposter’s Journey to Belong

- Women Are America’s Climate Change Champions

- Vegan at Sea-gan: The Arctic Ocean

- Golden Rule in Arctic Science and Community Partnerships

- Is the Future of the European Arctic Socially Sustainable?

- Geo-mapping in the Canadian Arctic

- Women in Polar Research: A Brief History

- It’s Our Table: Indigenous People Shaping Arctic Policy

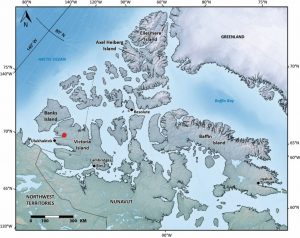

The GSC Base Camp, Victoria Island

[MCW] I am research geologist who carries out fieldwork, including geo-mapping, in remote areas of Canada’s North. The route to my summer field camps in the eastern Arctic Archipelago usually involves a trip from Ottawa to Resolute Bay, Nunavut, followed by several hours of additional flying by Twin Otter aircraft and helicopter to reach Axel Heiberg Island. This had been the summer routine for me until 2010. That year, for the first time in my career at the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), I was heading to Yellowknife en route to Ulukhaktok, Victoria Island, in the Northwest Territories.

There, I would join a large group of geologists to map parts of the island in the vicinity of Minto Inlet. I knew what it was like to carry out fieldwork from a GSC base camp: dedicated helicopters, hot meals, access to a hot shower and toilet tent, and best of all, the chance to socialise with a large group of people. That was going to be a nice change. As a field geologist, my standard mode of operation is an Arctic fly camp: two to four geologists camp out in the wilderness for a few weeks with their own food supplies and no one else in sight.

The landscape on Victoria Island was much more subdued than I had expected. None of the familiar mountainous, glaciated terrains, and deep fjords that are characteristic of the eastern Arctic Archipelago. Wide, gravelly rivers meander through rocky cliffs of sandstone and lava. The sky is big and the land immense.

The Victoria Island GEM Project (Geo-Mapping for Energy and Minerals), led by my colleagues Rob Rainbird and Jean Bédard, involved over thirty participants mapping the bedrock over the course of two summers. Base camp was no less than a small village of canvas tents that included kitchen and office tents.

A dozen students from universities in Canada and abroad provided all the energy needed to get the job done.

Two helicopter pilots flew geological crews daily from the Minto base camp to work sites all over the island from early June to August 2010.

In early July, an opportunity came up for me to spend a few days away from the GSC base camp. Two graduate students, my daughter Nicole Williamson from Carleton University and Trent Dell’Oro from the University of British Columbia, required field support and training in volcanology. They were to collect rocks and observations for their Masters’ degrees and needed an experienced geologist to show them how to make the most of the fly camps dedicated to their project. I accepted the job without hesitation. Volcanoes were my geological ‘love at first sight’ at age 16. Here was an opportunity to observe ancient lava flows emplaced in a Large Igneous Province that covered half of the island over 700 million years ago. I was looking forward to a few days of ‘no frills’ camping in the wilderness: cooking outside, working in a Logan tent, and sleeping on the permafrost, with no power supply and the only option of reaching the outside world via satellite phone should an emergency situation arise.

[NW] Incredibly, my mom and I had the unique opportunity to do fieldwork together in 2010. She is an experienced Arctic geoscientist, and at the time, I was completely new to fieldwork in northern Canada. I had completed multiple field courses during my undergraduate degree…but none of them took place in very remote areas. Looking back eight years later, I had no idea how special and unique it was to be so far north. It was my first real fieldwork experience and I felt totally privileged.

Favourite things include the absolute stillness of the landscape and constant daylight, the sun spinning circles in the sky during the very short Arctic summer.

Mapping Volcanic Rocks

We set up our fly camp at the base of a steep cliff of lava flows overlooking lakes and rivers.

The lava flows are much like those you would find in Iceland or Hawaii but they erupted on continental crust that was ruptured and broken by tectonic plates being pulled apart. The best rock exposures happened to be located at the top of the cliff where the wind howled constantly.

Our days outside were long and physically challenging. Every morning, we walked straight up to the top of the cliff under the watchful eye of our local muskox herd, and measured, sketched, photographed, and sampled the bedrock.

It was clear from the start that Nicole was ready to learn the ropes with laser focus.

After a few days of geological work, Nicole and Trent would tie up the heavy sample bags and rock cans with flag tape and set them up in neat piles on open ground. I watched from a distance as the students applied their training for the first time: signal the pilot with an orange tarp or field mirror, load up the rock samples, give a thumbs up, and hold in place while the machine takes to the skies again.

Work always continued well into the evening with more sample processing, photo, and data backups, a review of field sketches and notes, and all the technical preparations for the following day’s traverse.

The Natkusiak Formation is a ~1 km thick pile of volcanic rocks that record the onset and early development of the Franklin Large Igneous Province, a massive lava flooding event caused by the breakup of the ancient continent Rodinia. The rocks are spectacularly preserved given their ripe age of 720 million years! The overall objective of our work was to document their early history by measuring their thickness and distribution, describing their mineralogy, and collecting samples for geochemical analysis. Although rewarding, it was very tough work: plan, organize, execute, record, photograph, edit, eat, sleep, repeat.

Mother, Daughter and the Northern Wilderness

I am grateful for the moments other than the actual rock science that I successfully captured with my field camera.

At the time, the “mom” part of me was firmly pushed aside by the daily realities of leading our small field team. Still, I couldn’t help but think: “Wow, my daughter is all grown up, and here we are at the top of the world, both happily surrounded by spectacular rocks, wolves, birds, muskox, and wonderful people to work with!”

I did think it was a bit strange to be working in the same place as my mom. Looking back, and with the ability now to put myself in her shoes on account of being older and more (*cough*) mature, I can see what a special and unique situation it was. I can’t begin to imagine what it would be like to have my grown child with me, at 72 degrees north and a day’s flight from the nearest hamlet! But she sums it up perfectly, and I felt the same way: the “daughter” part of me was pushed aside by the reality of our situation. Working in a remote location is no joke – you need to have the ability to work effectively with your colleagues no matter who they are and where they come from. That includes my mom!

The entire experience was absolutely wild and beautiful.

The flora and wildlife were nothing short of bewildering to experience. Arctic wolves and muskox were our daily companions, as were snowy owls, hawks, falcons, and lemmings. We were living and working where the wild things are, and to me, that was completely awe-inspiring.

Community Engagement

Meeting and working with the people of Ulukhaktok had, in and of itself, a deep and meaningful impact on me for a few reasons. First, the people we met and worked with over the course of the two summers are incredibly generous and kind. They manifest a sense and instinct of their surroundings unlike anything I had seen before. They inspired me to look at, listen to, and feel the landscape around me.

Second, this experience was the first time I felt the true, applicable impact of science communication. Among many other exchanges, our project leaders discussed a map of our study area with the elders and explained our goals. This form of community engagement enabled us to share information with them, and them with us, creating a connection between traditional knowledge and geology. Third, although I had previously done some science outreach, the joy, importance, and impact of mentorship really hit me over the course of the two summers I spent on Victoria Island. The GSC team welcomed four high school students from the hamlet of Ulukhaktok to work with us as field assistants, all of them young women. I think that the hours we spent on foot traverses together had a real impact on their futures and showed them that many possibilities exist for women in science.

The Future is Bright

From the perspective of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), I have been incredibly fortunate. I have had a number of excellent mentors, and actually, the majority of them have been men. However, in my humble opinion, I have had the ultimate “women in STEM” mentor, a geoscientist mom. Growing up, I believed that being a woman in STEM was a non-issue. Having a mom who flew north from Resolute to carry out fieldwork in the Canadian Arctic Islands was totally normal to me. She worked in the field and in the lab, wrote papers, and travelled to conferences. As a result, I spent my teenage years loving any kind of science, particularly astronomy and theoretical physics, never thinking anything of it. Growing up with parents who were both geoscientists meant that there was no gender bias in science for me, period! The other side of this situation, however, is that I only became aware of inequality in STEM slowly but surely in my 20’s, as my experience in the geosciences grew. It is absolutely *not* a non-issue, and so promoting women in STEM has become important to me, mostly through mentoring of undergraduate students and science communication.

Selfie in the lab while analyzing olivine compositions from Kauai on the electron microprobe at the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, Manoa, in Honolulu.

The experience of carrying out fieldwork on Victoria Island certainly influenced what I did next. It showed me that I love fieldwork because it provides the background needed to tell a geological story using field observations and geochemical data. For my Ph.D., I continue to study volcanoes but this time in Hawaii – talk about a change of scenery! Specifically, I’m studying the geochemistry of lavas from the northernmost Hawaiian island of Kauai because they record a dramatic shift in the chemistry of the Hawaiian hotspot source. So far, Kauai’s lavas are revealing some interesting and important new information about the geochemical evolution of the Hawaiian hotspot and the chemistry of the Earth’s deep mantle.

Both Nicole and I returned to Victoria Island in 2011 to continue mapping the bedrock further south of Minto Inlet. We kept in touch by sending each other letters in the field that were kindly delivered by the helicopter pilots. I was principal investigator on the environmental and economic impact of iron-rich deposits known as ‘gossans’: rust-coloured outcrops that are typically associated with volcanic rocks and used by the mineral exploration industry as metal resource indicators. In collaboration with Rob Rainbird, I wrote a report on our scientific discoveries that includes snapshots of the GSC mapping team and our friends from Ulukhaktok, as well as a virtual geological field trip across the area targeted for mapping. Since then, I have resumed my fieldwork on Axel Heiberg Island, trading the vast expanses of tundra on Victoria Island for the steep cliffs, fjords, and glaciers of the Princess Margaret Range.

Looking back at what I learned in 2010-2011, I realize that it has become a reference point in my career as an Arctic scientist: What are the issues still facing us as field geologists working in the North? What is our legacy to Canadians and how can we share best practices as mentors of the next generation of geoscientists? What are the geological questions that remain to be answered in Canada’s Arctic regions? When I reflect on those days spent with Nicole on a windswept cliff in July 2010, I feel a dual sense of accomplishment: the GEM Victoria Island project was an anchoring point in my career and it gave me a unique opportunity to give Nicole some down-to-earth, boots-on-the-ground support when she needed it most, and in a very special way.

Marie-Claude Williamson is a research scientist at the Geological Survey Canada located in Ottawa, Ontario. Nicole Williamson is a PhD candidate at the Pacific Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research, University of British Columbia located in Vancouver, British Columbia.