Is the Future of the European Arctic Socially Sustainable?

A group of young people cycling in Oulu. Photo: Rami Hanafi

In recent years, women researchers, scientists, and local champions have elevated their visibility and empowered their voices across the world. The Arctic is no exception. With powerful organizations like 500 Women Scientists and local movements like Women in Polar Science and Plan A growing their reach and impact, women are sharing their personal narratives, highlighting their contributions, and supporting each other like never before. The Arctic Institute’s Breaking the Arctic’s Ice Ceiling is our team’s contribution to this movement. In a series of commentaries, articles, and multimedia posts, we are highlighting the work of women working and living in the Arctic.

The Arctic Institute Breaking the Arctic's Ice Ceiling Series 2019

- Looking Up: Women in Arctic Science

- The Gender Gap in Arctic Research Awards and Leadership – Infographic

- An Arctic Imposter’s Journey to Belong

- Women Are America’s Climate Change Champions

- Vegan at Sea-gan: The Arctic Ocean

- Golden Rule in Arctic Science and Community Partnerships

- Is the Future of the European Arctic Socially Sustainable?

- Geo-mapping in the Canadian Arctic

- Women in Polar Research: A Brief History

- It’s Our Table: Indigenous People Shaping Arctic Policy

The purpose of this article is to assess the gender dimension of social sustainability of the European Arctic. Social sustainability is defined as a socially sustainable system that achieves fairness in distribution and opportunity, adequate provision of social services, including health and education, gender equity, and political accountability and participation.1). In order to assess how the European Arctic performs in social sustainability, I employ the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDG) framework that includes 17 sustainable development goals that concern achieving economic growth and address a range of social needs including education, health, social protection, and job opportunities, while tackling climate change and environmental protection. I address the gender dimension of social sustainability by concentrating on the following UN SDGs: Goal 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), Goal 4 (Education), Goal 5 (Gender equality), and Goal 8 (Decent work and economic growth). In discussing these specific SDGs, I address challenges by providing questions and implications for policymakers.

I use data on demographic trends, education, employment, family, and work balance gathered through the Business Index North (BIN) project2). The 2018 report includes ten northern regions in Norway (Finnmark, Troms, Nordland), Sweden (Norrbotten and Västerbotten), Finland (Lapland, Northern Ostrobothnia, and Kainuu) and Russian regions (Murmansk and Arkhangelsk excluding the Nenets Autonomous Okrug). In terms of population, it covers 3.6 million people or 80% of the entire Arctic population and their development trends for the period 2007-2016.

Women are on the decline in the European Arctic

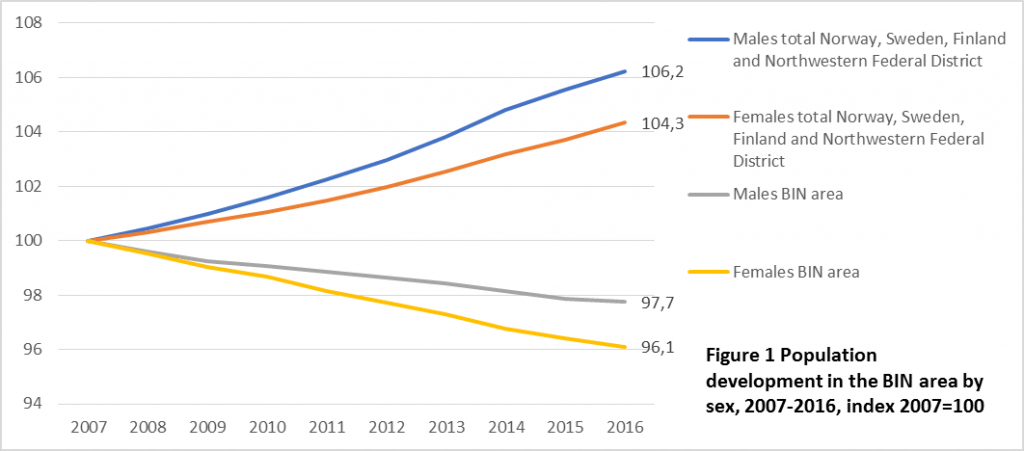

The BIN area experienced a population decline of 3.1% (144,379 people) during the period of 2007-2016. At the same time in Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Northwestern Federal District in Russia population continued to grow by 5.2% (1.8 mio. people). Figure 1 illustrates population development in the BIN region using indices for male and female population separately. Both male and female population in the BIN area are declining but the gender gap is widening with a 1.6 percentage points greater decrease in female population compared to male. Altogether, the BIN area lost 75,906 females over the period 2007-2016. The biggest decline in female population was driven by the Russian regions of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk.

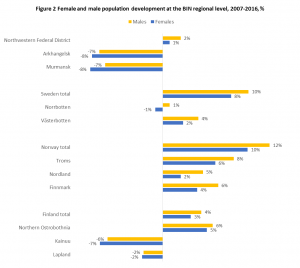

Wellbeing in the European Arctic depends on a healthy balance of male and female population

Analysis of the regional level demonstrates that there are significant differences in male and female population changes (see Figure 2). The Arkhangelsk (-8 %) and Murmansk (-8 %) regions had the biggest decreases in female population, followed by Kainuu in Finland (-7%). In the Norwegian and Swedish regions, the growth of female population lagged slightly behind the growth in male population. At the same time, I observe that the Finnish region of Northern Ostrobothnia was more successful in attracting female population with 2 percentage points ahead of the country average.

Population sex ratio ratio3) reflects a number of males per 100 females in the population. A population sex ratio that is above 1054) is considered skewed. On the municipality level, 27 municipalities out of 175 in northern Finland, Sweden, and Norway in 2006 had a sex ratio of 105, by 2015 the number of municipalities with skewed population sex ratio doubled, i.e. counting 54. The northernmost municipalities In Norway had population sex ratios as high as 117 (Gamvik) and 122 (Loppa); similarly in the remote Finnish municipalities of Savukoski and Utsjoki population sex ratio reached 122 in 2015. The share of female population is higher in urban areas and lower in rural areas. Research from Alaska5) and Greenland6) documented that female outmigration from small Arctic communities is driven by availability of jobs, education, career opportunities, and perceptions regarding the relative attractions of life in small and larger communities. Also in the European Arctic unbalanced population sex ratios are driven, amongst others, by outmigration by young adult females to pursue education and seek jobs in urban centres.

These findings serve to access how well the European Arctic is performing in achieving Goal 3 (Health and Wellbeing). What are the risks of the declining female population in the European Arctic? Communities with abnormal population sex ratios may lead to the young male population facing lack of marriageability, and consequent marginalisation in society leading to antisocial behaviour and violence.7) Research from East Asian countries8) demonstrates that abnormal population sex ratios in the population might be associated with social instability and violence.

This leaves questions for policymakers to consider. What are successful regions doing to attract female population? What are their public policies? The attractiveness of a place is determined by access to work, education, services, and cultural experiences. We need policies to address the future of wellbeing in the European Arctic regions by considering the gender dimension of social sustainability.

Highly educated women live in the European Arctic

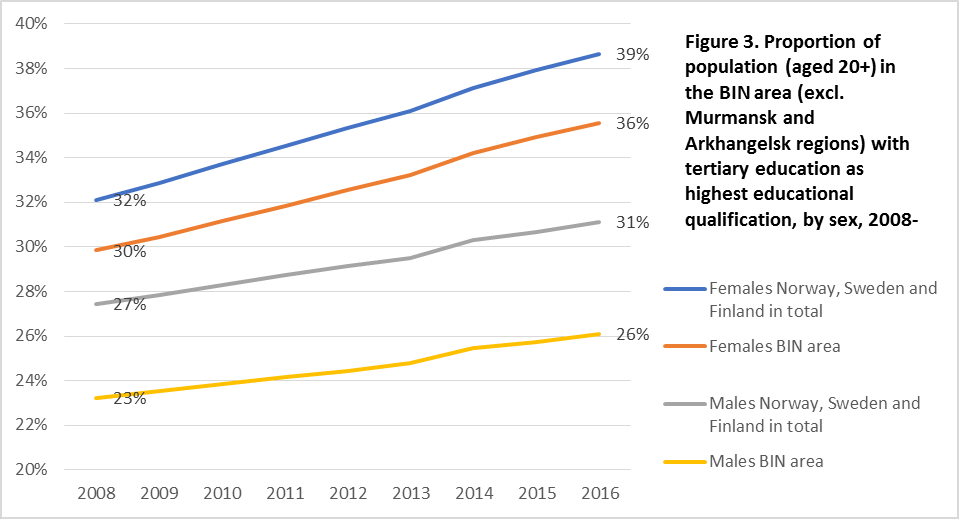

When analyzing how well is the European Arctic performing in Goal 4 (Education) and Goal 3 (Health and Wellbeing), I also studied the levels of educational attainment by concentrating on tertiary education. Tertiary education includes all three levels of tertiary education, i.e. Bachelor’s, Master’s, doctoral degrees, and equivalent. Highly educated people generally have better health, are more socially engaged, have higher employment rates, and have higher relative earnings.9) Moreover, the level of education is fundamental in predicting individuals’ health10) and life expectancy.11)

On average, 36% of women in the BIN area in 2016 have attained tertiary education compared to 26% of male population (see Figure 3). From 2008 to 2016 female tertiary education attainment in the BIN area (excl. Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions)12) increased by 6 percentage points and in 2016 was slightly below that of the Norway, Sweden, and Finland average of 39%. The region of Västerbotten (Sweden) boasted as many as 42% of all females having a tertiary education qualification. The tertiary education attainment of males in the BIN area remained rather low with an increase of 3 percentage points over a period of nine years, reaching just 26% of all male population. These statistics demonstrate that there is a large human capital potential of female population living in the European Arctic, while male population is lagging behind female population by an average 10 percentage points in attaining tertiary education. Imbalances in tertiary education attainment levels between men and women in the BIN area have long-lasting impacts on achieving Goal 3 (Health and Wellbeing) and Goal 4 (Education). The nature of work is changing all over the world with the proliferation of digitalization and automation. For BIN area regional development, this means job losses in traditional industries such as the mining, fishing, agriculture, and paper industry13) and job creation in sectors requiring skilled labour, e.g. human health and social care services and professional services. Policymakers need to address the challenge of providing equal opportunities for the male and female population. Low tertiary educational attainment amongst male population raises concerns on the employability of males in the future and has implications for their life expectancy prospects.

Work and family life in the European Arctic

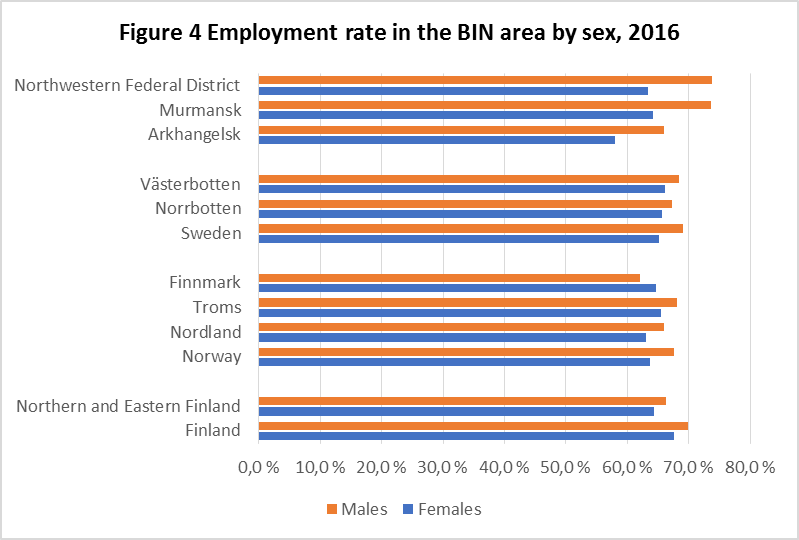

When assessing how well the BIN area is performing in addressing Goal 5 (Gender Equality) and Goal 8 (Decent work and economic growth), I use data on employment rates.14) Overall, women participate less in employment than men15)

Figure 4 demonstrates that employment rates for females are indeed slightly lower than for males in Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish regions. The employment rates of males are significantly higher in the range of 10 percentage points in the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions. This is at least partly due to an industry structure dominated by mining, quarrying, and the manufacturing sector in the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions. Women’s participation in the care of children and the elderly is also traditionally high in Russia, amplified by an “implicit conservative turn strengthening traditional gender roles which encourage women’s caring responsibilities and men’s breadwinning functions”.16) Moreover, social attitudes in Russia legitimize institutionalized inequalities in the labor market, whereby women earn only a fraction of what men earn.17) Previous studies confirm that the availability of quality childcare services is crucial to increasing women’s employment participation.18)

Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish regions perform rather well in providing conditions that result in nearly equal employment rates amongst men and women, hence contributing to achieving Goal 5 (Gender equality) measured as participation in employment. At the same time, Russian Arctic regions should focus on providing better employment conditions and opportunities for females, including quality childcare services and shared parental leave. But also work remains to be done in Nordic countries. In order to achieve Goal 5, these countries should systematically address gender gap issues, because “while the income gap between genders is slowly decreasing in the Nordic countries, women still earn less than men at all levels of the income distribution”.19) The same concerns Russia, where women’s salaries are on average 26 percent lower than those of men.20)

In sum, to achieve Goal 5 and Goal 8 from a social sustainability perspective in the European Arctic, policymakers should design policies and institutions that support family-work balance and provide equal opportunities for male and female population participation in the employment market.

Fewer children are born in the European Arctic

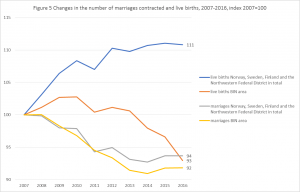

The notion of family is changing everywhere in the world.21) The trends include cohabiting, other forms of family arrangements, probability of having fewer children, later age of first childbirth for women and, childbirth without marriage. Figure 5 demonstrates that the same trend is observed in the BIN area, where the number of marriages has declined by 8% in the last ten years. The decline is greater than in the rest of Norway, Sweden, Norway, and the Northwestern Federal District in Russia, which is explained by shrinking youth (0-19 years) and working age population (20-64 years) in the North.

Decreasing female population in the European Arctic and a population structure with an increasing share of elderly people results in a decrease in live births (see Figure 5). While Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Northwestern Federal District in Russia collectively saw growth of 11 % in live birth changes, the BIN area saw a 7% decline in live births. This means that while in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Northwestern Federal District in Russia fewer marriages contracted do not result in fewer children born since the notion of family is changing including, e.g. consensual unions. EU statistics demonstrates that “live births outside marriage in the EU-28 has increased significantly in the last decade, signalling new patterns of family formation”.22) In the BIN area there is a positive correlation between fewer marriages and fewer children being born. This finding demonstrates that the BIN area fails to attract new families and young females regardless of their marital status, hence live birth statistics are negative during 2007-2016. What are the consequences of this trend? Fewer children born in the BIN area will increase the pressure on the social systems. Family issues require effective decisions on many scales, including migration policies, attractive living conditions, and policies for childcare sharing between parents. These challenges highlight the necessity of addressing gender perspective when designing policies to address Goal 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing).

Conclusion

The evaluation of the gender dimension of social sustainability performance in the BIN area is not straightforward. This European Arctic experiences big demographic structural changes with a rapidly growing aging population, decreasing share of females in remote municipalities, and decreasing young and working age population, which are all crucial components of social sustainability. There are significant gender differences in achieving Goal 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing) measured as life expectancy at birth. Women live longer: the life expectancy of girls at birth in 2015 was 83 years in Northern Norway, Sweden, and Finland, which is 4.5 years longer than for boys born in 2015. In the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions, life expectancy for girls at birth was 76 years, which is 10.6 years longer than that for boys. Data shows that the female population in the BIN area is declining, which poses challenges for the future of social stability and sustainability of the European Arctic. In achieving Goal 4 (Education), the female population in the BIN area demonstrates high levels of tertiary education attainment while the male population underperforms by five percentage points below Nordic countries average. Nordic Arctic regions perform better in achieving Goal 5 (Gender Equality) and Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) compared to the regions of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. However, the whole BIN area needs targeted measures for improving gender equality in terms of eliminating the gender pay gap.

Moreover, the notion of family is changing and fewer children are born in the BIN area. In order to achieve sustainable social development, we need policies that have a long lasting effect. For instance, measures to attract women to study, build their careers upon their education, and establish families in the European Arctic are crucial. Migration policies should be designed built upon the understanding of demographic and social sustainability trends in the European Arctic. Similarly, measures to improve tertiary educational attainment amongst men should be high on the agenda. Detailed regional and municipality data demonstrates that some regions are already successful in achieving these goals. We need to learn from each other and share practices and policies that result in thriving, inclusive societies to create the socially sustainable Arctic communities of tomorrow.

Alexandra Middleton is a Postdoctoral researcher at Oulu Business School, University of Oulu, Finland.

References