In the Fog of War: Russia Raises Stakes on the Russian Arctic Straits

The Virginia-class fast attack submarine USS Illinois (SSN 786) moors in Arctic sea ice in the Beaufort Sea during Ice Exercise (ICEX) 2022. Photo: U.S. Navy

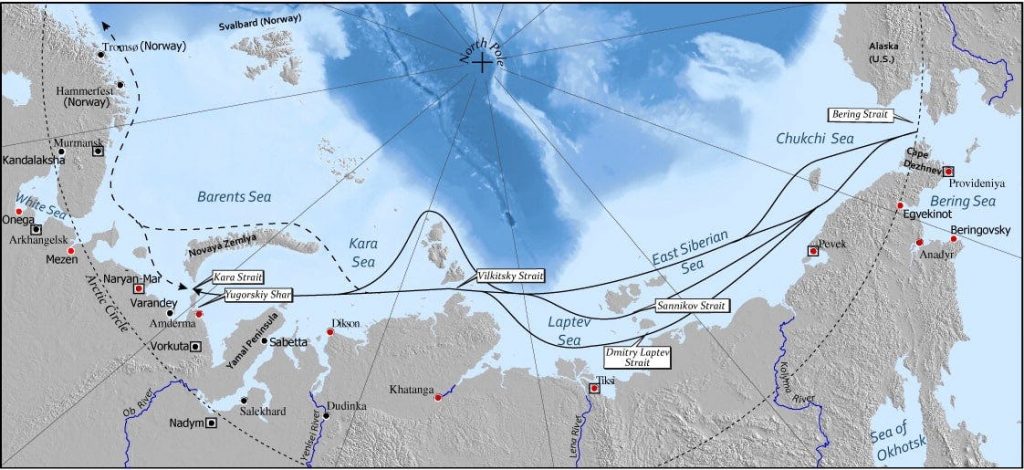

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is an unexpected casualty of the war in Ukraine. Due to the sanctions regime, and the generally strained relations between Russia and the West, the long-held vision of an economically viable North-East Passage (NEP) between the Pacific and Atlantic ports via Russian Arctic straits might be clinically dead. However, what might be over (or only left aside) is one specific vision of the NEP – emphasizing the utility of a geographically shorter route for economic exchange, cracked open by climate change.

We got used to thinking of the NSR in commercial terms, but in the aura of the Arctic as a zone of peace and cooperation, we almost forgot of its geopolitical utility, namely being a short(er) passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific. In the future, the NSR might be used for non-commercial purposes, for example, by foreign warships. The harsh reality is that who controls the straits controls the NEP. While it is theoretically possible to circumnavigate the Russian Arctic straits and use the NEP, the US experience from the 1960s’ (as thoroughly covered by Roach and Smith’s Excessive Maritime Claims) is not particularly uplifting.

The terms of use of these areas, and specifically the Russian Arctic Straits, is a matter of international law of the sea, primarily the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The law of the sea reconciles the inclusive interest of the international community in global mobility (freedom of navigation) with the exclusive interests of coastal States in authority over marine areas adjacent to their coasts. It provides stability by providing a way of dividing the entire globe into maritime zones, subject to navigational rights and freedoms. The balance is not carved in stone, as States might pursue their particular interests by making claims reflecting their understanding of the applicable rules. The flexibility of international law is nourished but also controlled through the action-reaction paradigm and notions such as acquiescence. For instance, the United States actively uses diplomatic channels and the Freedom of Navigation (FON) Programme to influence other States to avoid or renounce maritime claims perceived as excessive.

Russia has for decades claimed that the waters in most NSR straits have the status of internal waters. However, under international law of the sea, a right of innocent passage (Article 8(2) of the UNCLOS) or transit passage (Article 35(a) of the UNCLOS) can still apply in internal waters unless they are considered historic waters. For the 90 years of the operation of the NSR, Russia (or the USSR) never publicly articulated any consistent historic waters claim for the waters in the NSR straits. Instead, Russia managed to control the Arctic straits by resorting to ambiguity, not ruling out a claim of historic waters. However, not making an explicit claim allowed Russia to fend off the potential diplomatic protests from other States. Russian international law authors seldom discuss the status of straits explicitly, except for presenting the issue as quite an uncomplicated case of complete sovereignty. Statements by academics, however, carry little weight in international law, and they do not fit in the action-reaction paradigm.

Contrary to the narrative of Russian academic writing, the issue of applicable navigational rights in the Russian Arctic straits is undetermined, contested, and of immense potential importance in the future. The United States considers some NSR straits as “used for international navigation”, implying the applicability of the regime of transit passage. The present author has argued elsewhere that Article 8 (2) of UNCLOS preserves the right of innocent passage in all NSR straits, with no need for previous acceptance, acknowledgment, or use.

In the shadow of the war in Ukraine, Russia prioritizes the Arctic and shapes its policy and practice stepwise. After amending the system of the Russian baselines, the recently published Maritime Doctrine focuses on the naval activity of foreign states in the water area of the NSR. The 2022 Draft Law seeks to double down on the call to exercise control over foreign warships in the NSR and preserve the historically established international legal regime of internal waters in the Arctic straits of the NSR, whatever that means.

It is vital to follow the developments in Russian Arctic legislation. The Russian Duma is now mulling a new law to substantiate the Russian claim to the NSR Straits. The law proposes requiring foreign warships and other State-owned ships to seek authorization for passage through internal waters within the NSR at least 90 days before entry, coupled with a mechanism to effectively prohibit innocent passage of unwanted foreign State vessels in the Russian territorial sea.

When seen in the context of the documents already adopted, this process will likely get completed this Fall. The drafts do not explicitly mention the historic title, but the substance of the proposed legislation paves the way for this topic to arise sooner or later. Regarding the action-reaction paradigm of international law, other States must prepare to react or risk acquiescence.

This contribution introduces the following NCLOS Blog post by Jan Jakub Solski, “New Draft Law on the Russian Arctic Straits – Putin’ Money Where the Mouth is?” (September 14th, 2022). The post discusses in more detail the new Russian draft law addressing access of foreign warships to straits in the Northern Sea Route (NSR). It analyses the proposed legislation in the larger context of other documents recently adopted by the Russian Federation: the 2021 Decree on Arctic Baselines and the 2022 Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation.

Jan Jakub Solski is a postdoc at the Norwegian Centre for the Law of the Sea, the UiT – the Arctic University of Norway.