Fly-in Fly-Out Workers in the Arctic: The Need for More Workforce Transparency in the Arctic

Flock of White Seagulls. Photo: Engin Akyurt

With the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the world has found itself in a global health emergency, which has caused a dramatic loss of human life worldwide and brought normal life around the world to a halt for the better part of a year. The Arctic Institute’s COVID-19 Series offers an interesting compilation of best practices, challenges and diverse approaches to the pandemic applied by various Arctic states, regions, and communities. We hope that this series will contribute to our understanding of how the region has coped with this unprecedented crisis as well as provide food for thought about possibilities and potential of development of regional cooperation.

The Arctic Institute COVID19 Series 2020-2021

- COVID-19 in the Arctic: The Arctic Institute’s Winter Series 2020-2021

- COVID-19 and Arctic Search and Rescue, our Duty to Act

- Vulnerable Communities: How has the COVID-19 Pandemic affected Indigenous People in the Russian Arctic?

- Brazilians in the Arctic: A Global Experience with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- COVID-19’s Impact on the Administration of Justice in Canada’s Arctic

- Isolation and Resilience of Arctic Oil Exploration during COVID-19: Business as usual or Structural Shift?

- COVID-19: How the Virus has frozen Arctic Research

- Rethinking Governance in Time of Pandemics in the Arctic

- Russia’s COVID Blinders: Arctic Policy Changes or Lack Thereof

- Geography of Economic Recovery Strategies in Nordic Countries

- Fly-in Fly-Out Workers in the Arctic: The Need for More Workforce Transparency in the Arctic

- Measures Taken by the Canadian Coast Guard to Respond to the Pandemic in the Canadian Arctic

- COVID-19 in the Arctic: Final Remarks

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic in the world, numerous exploration and construction sites in the Russian Arctic reported large infection outbreaks. For instance, there were 2,045 cases of infection in the Murmansk region at the Belokamneka construction site for Novatek in May, making it the fifth most affected region in all of Russia. The site employs more than 10,000 workers that work on a fly-in fly-out basis. People, as a rule, live in modified shipping containers, with eight workers sharing 20 square meters, making it very hard to prevent the spread.1) The global COVID-19 pandemic brought to light the scale of fly-in fly-out labor employed at the Arctic projects. Arctic development that involves large influxes of fly-in fly-out and migrant labor poses risks to the workforce and to the local communities.

This article aims to bring awareness to the need for greater transparency of labor arrangements and conditions in the Arctic. It is necessary not only for Russian projects but also for those in Greenland, Canada, and any other Arctic country that expects big investments and large inflows of fly-in fly-out labor. Solutions discussed here include: on the national level- improved national statistics records, on the corporate level-modern slavery reporting by companies, and on the local level- design of equitable benefit-sharing agreements.

Risks of fly-in fly-out work arrangement

Fly-in fly-out work is a rotational system in which employees spend a certain number of days working on site, after which they return to their home communities for a specified rest period. As a practice, employers organize and pay for transportation to and from the worksite and for worker accommodations. Fly-in fly-out work has become the standard model for new mining, petroleum and other types of resource development in remote areas.2) Fly-in fly-out model flourished because of a cost reduction chase. It does not require investments into industrial town development, allows for lean and flexible management, and access to a larger supply of qualified workers. This model comes with an array of negative social effects on the local community and on the workers themselves.3) Fly-in fly-out work can involve migrant workers persons who move away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons.4) The risks involved with migrant workers are racism, discrimination and unfair working conditions.

National statistics records as a rule do not include data on fly-in and fly-out or migrant workers, in case some information is available it is reported on a country-wide scale without regional subdivision, hence making it unable to attribute to the Arctic. Modern slavery reporting is a tool available to the companies that are willing to become more transparent in reporting about their labor practices, standards and labor supply chains. Modern Slavery5) is an umbrella term that refers to both sex trafficking and compelled labor; it may include exploitation of other people for personal or commercial gain. Forced labour and labour exploitation that involve control, force or coercion of an individual to perform work are also parts of modern slavery. Migrants are particularly vulnerable to labor exploitation. In 2015 the UK introduced the Modern Slavery Act including six areas to report on (organisation structure and supply chains, policies in relation to slavery and human trafficking, human rights due diligence processes, risk assessment and management, key performance indicators to measure effectiveness of steps being taken, training on modern slavery and trafficking).6) followed suit, requiring a new statutory modern slavery reporting requirement for larger companies operating in Australia. According to the Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018, entities with AUD$100 million annual revenue must produce an annual public statement describing the risks of modern slavery practices in the operations and supply chain that they are doing to address modern slavery risks.

In the lack of transparency and reporting, it is unknown to what extent modern slavery risks are prevalent in the companies operating in the Arctic; this article brings attention to existing and emerging risks.

The scale of Arctic projects

Numerous ongoing and future hydrocarbon development and infrastructure projects in the Arctic require transient labour that cannot be sourced from the local communities. In Russian Arctic oil and gas projects since 2017, tens of thousands of construction workers from across the country, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and also from China, Turkey, and Central Asia, worked at oil and gas fields across the Russian Arctic.7) The massive COVID-19 outbreaks have highlighted the scale of the fly-in fly-out workers in the Arctic, and the vulnerability of workers and local populations. Workers in Belokamneka had to be quarantined, and a mobile coronavirus hospital was erected to treat 700 patients; meanwhile, at hydrocarbon fields in the Yamal Peninsula, more than 20,000 people were cut off from the world due to quarantine and cancelled flights.8)

The fly-in fly-out model puts a strain on the local medical and social services, and the pandemic situation emphasized the lack of planning for resource development. The mobile hospital in the Murmansk region, which cost USD 12.7 million9) was never filled to capacity. Yet it did not serve the local population in spring-summer 2020 either, with equipment from it being distributed among Murmansk region medical facilities only in autumn 2020.10)

These examples demonstrate how little we know about who and under what conditions works on big Arctic projects.

Migrant workforce dilemma

Labor brought as part of foreign investment is often a dividing factor with a delicate balance between benefits and challenges brought to the local communities. Chinese interests in the Arctic are fuelled by economic considerations and thirst for raw materials. Studies from outside the Arctic bring to attention tensions between local communities and Chinese workers and Chinese labor model and standards, with a poor record of Chinese labor environmental and social impact.11) In Greenland, employment of Chinese workers as part of Chinese investments12) and bringing Chinese workers for extensive mining projects is perceived as a threat to Greenland societal security.13) Big infrastructure projects and employment of fly-in fly-out workers in the Murmansk region created tensions among the local population. The Governor of Murmansk, Andrey Chibis even made a special announcement that there will not be Chinese workers employed in construction of Lavna coal handling terminal creating more than 1,000 jobs.14)

Migrant and fly-in fly-out workers are portrayed as invaders and a plague to local employment. The hostile sentiment towards migrant workers is a widespread phenomenon rooted in among others xenophobia. Migrants from Central Asia living in Russia report experiencing racism as part of everyday life15) and Chinese migrant workers are often scapegoated in the host countries.16) It can be argued that all fly-in-fly-out workers that represent domestic and migrant workforce in the Arctic are themselves vulnerable to conditions and working standards applied. Similarly, Arctic communities that are affected by big extractive and infrastructure projects become vulnerable to the influx of transient labour and struggle to cope with increased services and infrastructure demands.

What can be done about this? First, what is missing from the current understanding of the Arctic is the transparency of information on labor employed in the Arctic projects. Shift workers are not captured in the national statistics, and any available data are fragmented.

Reporting by companies

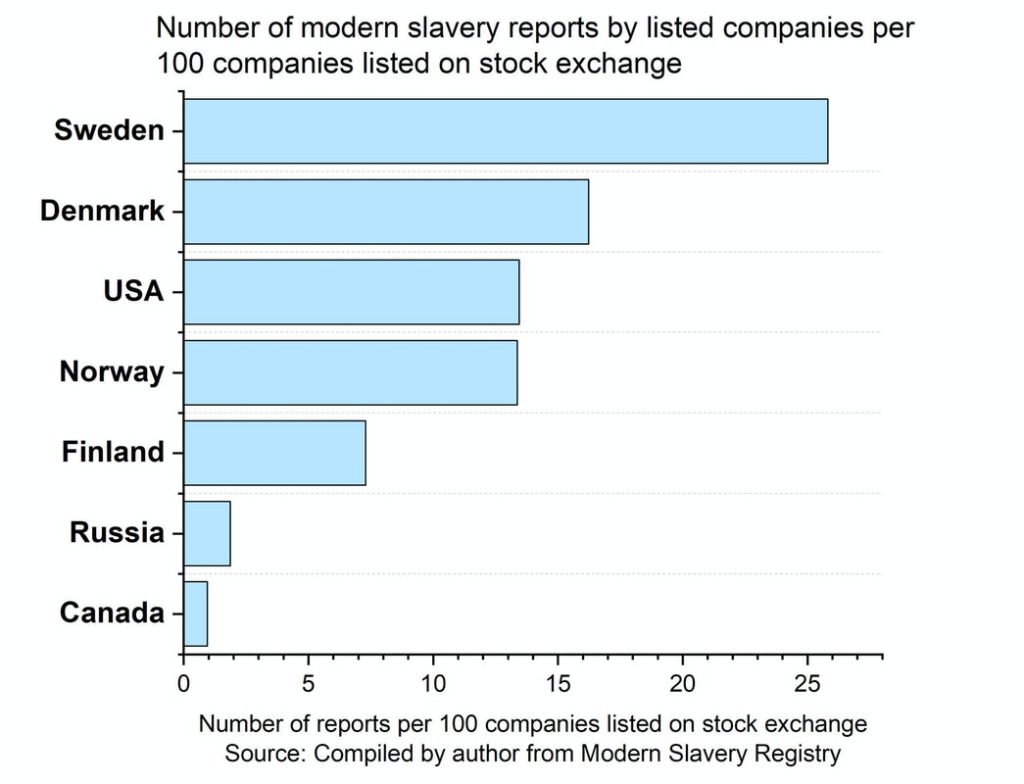

Given the pace of development in the Arctic, the influx of migrant labor and fly-in and fly-out workers, I consider Modern Slavery reporting especially relevant for the companies operating in the Arctic. One way for the companies to address the transparency of labor issue in the Arctic is via modern slavery reporting. Modern Slavery reporting is not compulsory for the companies in the Arctic states, and the rate of uptake is very low. Graph 1 summarizes the number of modern slavery reports of listed companies that are registered in Modern Slavery Registry, maintained by The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre.17)

As a minimum, a company should report on existing processes and practices related to modern slavery, as well as labour standards more generally. Such a report should include integration of employment, whistleblowing, migrant labour and child protection policies in the context of a broader human rights due diligence context.18) I accessed data from the Modern Slavery Registry and used statistics available starting from 2015 on the Arctic states and adjusted it to the stock market size. The results show that the Swedish listed companies produce most Modern Slavery reports per 100 listed companies, while Canada and Russia have the least reporting companies. However, the number of reports per se does not guarantee quality and depth of information provided since on average only 21% of all reports anlayzed in Graph 1 meet minimum reporting requirement as per the UK the Modern Slavery Act. The goal of the reporting is the change in working standards and practices and genuine accountability, not a simple tick box exercise.

Relevance for the Arctic

By producing modern slavery reports that at least meet minimum standards, the companies can demonstrate their acknowledgement of the problem and take measures to address the threats of vulnerable people working conditions and monitor their supply chains for modern slavery risks. Modern slavery reporting could also create a larger awareness of labor conditions and raise the standards of workforce employment in the Arctic. The fly-in fly-out workers represent a phenomenon that is pertinent to the whole Arctic and is only going to become more prominent in the years to come. For instance, ambitious projects by Northvolt19) and Fryer20) for green batteries production in the North of Sweden and Norway will create an estimate of 4,000 new jobs many of which will be serviced by fly-in fly-out workforce.21)

Benefit share agreements

One way to address fly-in fly-out workers’ challenge for the local community is the use of benefit share agreements aiming to re-distribution of monetary and non-monetary benefits generated through the resource extraction activity to the local communities. Analysis of existing benefit share agreements reveals their patchiness and heterogeneity across the Arctic.22) Ideally, Arctic communities should be involved in co-management and participate in benefits planning that are reflective of particular community needs, e.g. health and social services.

Solutions for increasing transparency on fly-in fly-out workers in the Arctic

To summarise, the COVID-19 outbreaks highlighted the scale of fly-in fly-out labor and vulnerability of both workforce and local communities. To address this, the following steps could be taken increasing labor transparency in the Arctic via:

- Improved national statistics on fly-in fly-out, including migrant workforce in the Arctic

- Commitments by companies involved in the Arctic projects to address human rights due diligence and Modern Slavery risks by following at least minimum reporting requirements

- Assessment of local infrastructure and service capacities to accommodate the needs of fly-in fly-out labour

- Evoking benefit-sharing agreements in which the local community has a fair say

The phenomenon of fly-in fly-out migrant workers in the Arctic is definitely a challenge that needs to receive more academic research and more discussion on the political level. This article only scraped the surface and identified potential avenues for research. The pace of large projects in the Arctic is accelerating. The solutions regarding labor arrangements that are transparent, fair, and respectful of human rights and local communities’ needs are to be explored the sooner, the better.

Alexandra Middleton works as Assistant Professor at Oulu Business School, University of Oulu (Finland).

References