The European Union and its Member States in the Arctic: Official Complementarity but Underlying Rivalry?

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell during the EU Arctic Forum in Brussels on 10th November 2021. Photo: European Commission – Audiovisual Service

The Arctic Institute EU-Arctic Series 2023

- The Arctic Institute’s 2023 Series on the European Union’s Arctic Policy – From a Stakeholder Perspective

- The European Union and its Member States in the Arctic: Official Complementarity but Underlying Rivalry?

- The Crossroads of Science Diplomacy: Italy and the Challenges of the European Union’s Greener Engagement in the Arctic

- Navigating Uncertainties: Finland’s Evolving Arctic Policy and the Role of a Regionally Adaptive EU Arctic Policy

- Mapping Estonia’s Arctic Vision: Call for an Influential European Union in Securing the Arctic

- A Path to Dialogue: The Arctic for EU-Russia Relations

- The Sámi Limbo: Outlining nearly Thirty Years of EU-Sápmi Relations

- How to streamline Sámi rights into Policy-Making in the European Union?

- Why should the European Union focus on co-producing knowledge for its Arctic policy?

- Time for Systems Thinking in the Arctic? The Need for Aligning Energy, Environmental and Arctic Policies in the European Union

- The Arctic Institute’s 2023 Series on the European Union’s Arctic Policy – Final Remarks

“We believe that there should be more EU in the Arctic and more Arctic in the EU”1)

Ever since the former Finnish Prime Minister pronounced these words in the Arctic Circle Assembly (2019), when Finland also had the presidency of the Council of the European Union, they have become a catchphrase repeated at every Arctic conference. What it really means for the different Member States of the European Union (EU) regarding the EU Arctic Policy remains unclear, however.

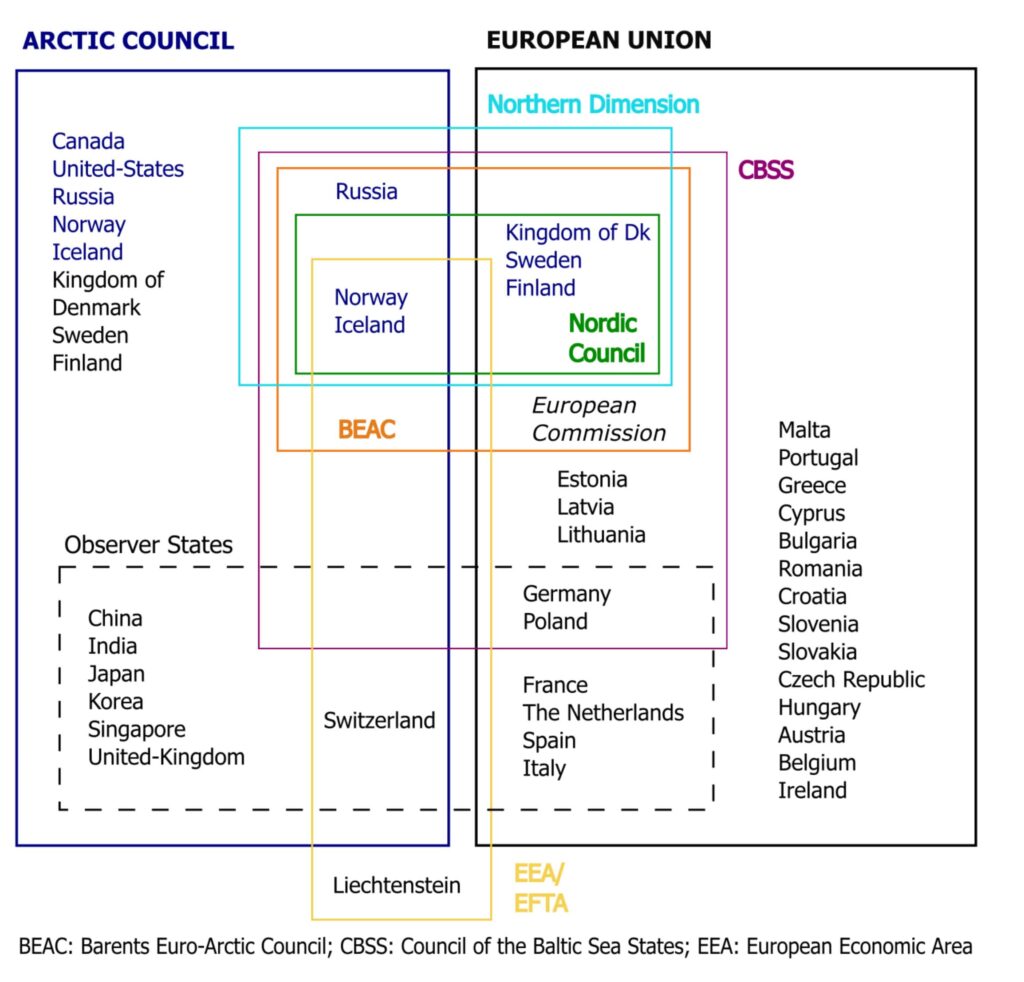

The EU is a Union of States. The Member States (MS) “confer to the Union competences to attain objectives they have in common” (Art. 1 of the Treaty of the European Union (TEU)). As such, the EU is a unique and original political entity that has a sophisticated institutional and legal architecture. This aims to guarantee a balance between the interests of the States, the interests of EU citizens and supra-national European interests (Art. 13 TEU). As a result, different institutions (the Council, European Commission and European Parliament) participate in the elaboration of the EU Arctic policy. This policy has both internal and external aspects. In the latter the 27 MS must often find a common position before acting, especially in foreign and security domains.2) Europe and the Arctic are linked through the EU political structure and Arctic governance institutions (see the Figure below). Three EU MS -Denmark, Finland, and Sweden- and two states closely associated with the EU -Iceland and Norway- are members of the Arctic Council (AC). Moreover, the AC welcomes non-Arctic states (as well as other entities) as Observers. Six Observer states are currently EU MS. Four other EU MS have applied since 2020.3)

All these MS have published policy documents detailing their interests in and for the Arctic and the Commission published its first Arctic policy document in 2008. The same year it applied to become an Observer to the AC, without success so far.4) Since then, there has been a call for enhanced coordination within the EU institutions and with the MS.5)

This article provides a comparative overview of the varying appreciation(s) of the role and place of the EU in Arctic governance6) by these MS (Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden). To do so, national policy documents,7) EU policy documents,8) and AC observer campaign documents have been analysed (see the table below) through critical geopolitics lenses.9) This article is also informed by observations done during several Arctic conferences in 2022-2023 and by more than 20 qualitative interviews with Arctic and European stakeholders. By understanding the political discrepancies or tensions -despite shared normative goals,10) I hope to shed light on the consequences for future cooperation in the Arctic between the MS and the European institutions. Based on this study, I offer thoughts on what leeway there is for a stronger “geopolitical” EU in the Arctic as envisaged by the Commission President11) or High Representative.12)

| Publication Year | Document Title |

|---|---|

| 2008 | Commission Communication on the European Union and the Arctic region |

| 2009 | Council conclusions on Arctic issues |

| 2010 | Finland – Finland’s strategy for the Arctic region Netherlands – The Netherlands and the Polar regions, 2011-2015 |

| 2011 | Sweden – Sweden’s strategy for the Arctic region Kingdom of Denmark – Strategy for the Arctic 2011-2020 |

| 2012 | Joint (Commission and EEAS) Communication on Developing an European Union policy towards the Arctic region: progress since 2008 and next steps |

| 2013 | Finland – Strategy for the Arctic region UK – Adapting to change: UK policy towards the Arctic. Germany – Leitlinien deutscher Arktispolitik: Verantwortung übernehmen, Chancen nutzen |

| 2014 | Council conclusions on Developing an European Union policy towards the Arctic region |

| 2015 | Italy – Towards an Italian strategy for the Arctic: national guidelines |

| 2016 | Spain – Guidelines for a Spanish polar strategy Netherlands – Pole position NL 2.0: Strategy for the Netherlands polar programme 2016-2020 Joint Communication on An Integrated European Union policy for the Arctic France – Le grand défi de l’Arctique : feuille de route nationale sur l’Arctique Council conclusions on the Arctic |

| 2018 | UK – Beyond the Ice: UK policy towards the Arctic |

| 2019 | Germany – Leitlinien deutscher Arktispolitik: Verantwortung übernehmen, Vertrauen schaffen, Zukunft gestalten Council conclusions on the EU Arctic policy |

| 2020 | Poland – Polish polar policy: from past expeditions to future challenges Sweden – Sweden’s strategy for the Arctic region Estonia – Estonia: towards observer status in the Arctic council. Estonia as an aspiring Arctic council observer state: the Arctic’s inventive neighbour Ireland – Ireland’s application for Arctic council observer status Czechia – Czechia in the Arctic / the Arctic in Czechia. Czechia on its way to achieving Arctic council observer status |

| 2021 | Finland – Finland’s strategy for Arctic policy Netherlands – The Netherlands’ polar strategy 2021-2025: prepared for change. Joint Communication on A stronger EU engagement for a peaceful, sustainable, and prosperous Arctic |

| 2022 | France – Équilibrer les extrêmes : stratégie polaire de la France à l’horizon 2030 |

Evolution of the place of the EU in the national Arctic strategies

All national documents are mentioning the EU, aligning with the EU’s objectives,13) and supporting its application for the Observer status. However, the degree and nature of support to the EU in the Arctic and the level of coordination with the EU Arctic policy varies among the MS. The early policies advocated for a strong and integrated European Arctic policy, arguing that a “European role will lead to synergy and economies of scale”.14) These documents contain a whole section or sub-section dedicated to the EU and its role in the Arctic governance. In the latest documents however, the size of the section referring to the EU is often reduced to a paragraph and the number of mentions of the EU has decreased.15) Mentions of the EU are now scattered throughout the document and consist of the different EU programmes and policies applicable to the Arctic. I examine how this can be interpreted below. The most cited policy areas are the EU research programmes and funding, the regional/cross-border cooperation initiatives and framework policies such as policies pertaining to maritime affairs and fisheries, Horizon 2020, or the Green Deal in the latest ones.

Is there really a Nordic bloc?

Denmark, Finland, and Sweden share a particular position as Arctic MS and play a significant role in EU-Arctic relations. The titles of their documents – simple and straightforward, whilst the documents by non-Arctic MS have often longer fancy titles designed as catchy slogans (see the table above) – distinguishes them from the other MS. These documents show that the Nordic states take their Arctic legitimacy for granted, but also that these policies have slightly different purposes than the policies of non-Arctic MS. The latter are not only aimed at an external Arctic audience but also at convincing their own administration of the importance of the Arctic for the country.

All three are supporting greater EU engagement in the Arctic and have an interest for the Arctic to be higher on the EU agenda both as an internal and external dimension. Their closer cooperation within the EU on Arctic matters was highlighted by all Nordic interviewees. The main obvious difference with the non-Arctic states is the domestic importance of the Arctic for them, which translates in their relations with the EU’s Arctic policy. It isin their national interest that “whenever the EU decides or devises new policies, that these policies take into account the Arctic conditions”16) of these countries. Yet, they have a varied attitude towards the EU Arctic policy and the EU’s engagement in the region.

Finland has been involved in shaping the Arctic as an international region from the end of the 1980s17) and is the most integrated Nordic State to the EU.18) Finland uses its Arctic identity within the EU context to advocate for an Arctic dimension to the internal EU policies and a strong EUropean foreign policy interest in the Arctic. Finland proposed to develop a Northern Dimension to the EU’s policies during its first EU presidency and the Northern Dimension is mentioned many times in the Finnish strategies.19) The Finnish Arctic policy documents highlight a sense of responsibility within the EU and a strong Finnish agency in EU-Arctic relations. Finland is using the Arctic to negotiate its position within the EU and shape the decisions of the EU on the Arctic by positioning itself in two ways: Finland as key provider of solutions to Arctic problems, and Finland as an attractive territorial node linking the Arctic region to Europe.20)

Dubbed “the reluctant Arctic citizen” by Sörlin,21) Sweden has been less involved in Arctic politics. Sweden supported the push for cooperation in the Arctic and applied for EU membership with which its international stance as peacemaker aligned. While Sweden is now replicating the Finnish calls for more EU-Arctic relations in political discourses, it is not necessarily working towards these.22) The 2011 Swedish policy reveals an ambiguous relationship to the Arctic: while claiming to be an Arctic country, it talks of the region from the perspective of a European country. The 2020 policy is showing a stronger Arctic perspective. Moreover, the launch of the Swedish EU presidency took place in Kiruna in January 2023 and emphasized developments happening in the Swedish Arctic (such as rare earth mineral mining). However, these developments are directed towards the EU/Europe and the important role that it grants to Northern Sweden rather than towards the Arctic region.23)

The relationship of Denmark with the EU regarding the Arctic is complicated due to the internal structure of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom is composed of three entities, of which only Denmark is an EU MS. The Faroe Islands were never part of the European Economic Community (EEC)/EU and Greenland left the EEC in 1985 after a referendum. Greenland is now an Overseas Country and Territory with a special agreement with the EU. The Kingdom of Denmark is a member of the AC thanks to its sovereignty over Greenland24) that is “centrally situated in the Arctic”.25) The EU is usually the most important venue for Danish foreign policy. However, Danish politics towards the Arctic are mainly conducted outside the EU and it is notable that the EU is little mentioned in the 2011 policy. Whilst Denmark is generally in favour of more EU engagement in the Arctic, it is only with certain limitations to the EU’s geopolitical influence and control over the daily life of the Arctic peoples.26) Thus, for Denmark, more EU engagement in the Arctic does not mean in all areas, nor that Denmark is leading EU interests in the Arctic.27)

The varied Arctic profiles of the non-Arctic EU Member States

The titles of the documents of the EU non-Arctic states reveal different visions of the Arctic as well as various positioning towards the region (see the table above). France shows the ambition of being a leading Arctic and polar nation with similar narratives of environmental protection of a common good, geopolitical necessity and scientific interests. French Members of the European Parliament (such as Michel Rocard, along with the British MEP Diana Wallis)28) influenced the early EU stance towards the Arctic. France has indeed envisioned its own polar identity and ambitious vision for the region as a leading role in shaping the EU’s policy. It used its 2008 Presidency of the EU to shape the EU Arctic policy29) and was also supportive ofthe European Parliament idea of an Arctic Treaty.30) France’s 2016 and 2022 documents are among those mentioning the most the EU. It has also been a strong supporter of the ban on hydrocarbons put forward in the latest EU document.31) This moral and political stance is coherent with France’s historic position towards the Arctic as an environmentally sensitive area that needs to be legally protected. Nevertheless, in public performances (such as during the EU Arctic Forum held in Brussels in October 2021) the French narrative is somewhat undermining the EU geographical narrative of the EU being in the Arctic. It explicitly emphasises that France is not using any geographical argument and being dismissive of others using it. Even though this is the narrative of France as a single state, whilst the EU document concerns the whole EU, it questions the EU’s potential of being a unitary geopolitical actor.

Germany and the Netherlands are early Observers to the AC. In their documents, the EU is not used as a platform to push forward national interests in the Arctic. Coordination with the EU policies is promoted, especially when it comes to research at the EU level and between MS. The Mosaic expedition and the organisation of the Third Arctic Science Ministerial Meeting (ASM 3) are two good examples of this. Poland shares with the Netherlands the characteristic of being a proactive observer in the AC, with the creation of the Warsaw format specific to the Observers. However, none of them have created a specific European observers’ discussion format.

Italy and Spain have less ambitious strategies but maybe more adapted to their actual means than, for instance, France that has an ambitious Polar strategy on paper, but very little funding dedicated to implement it.32) They would benefit from stronger EU coordination. In its Polar strategy, Spain proposed to create a specialised commission for polar issues as part of the EU’s common foreign and security policy.

Finally, among the applications for observer status, EU membership is not used as an argument and alignment with its policy is not highlighted. Only Estonia (which is also the most pro-active applicant) is using its membership to the EU as an argument in favour for its application. It was also the only EU non-Arctic MS that participated in the EU Arctic forum in Nuuk in February 2023. How Belgium will develop its argument as they are drafting their Arctic policy (and potentially applying to the AC33) will be interesting given that a lead person is Marie-Anne Coninsx, former EU ambassador for the Arctic.

Scale and power: How far can the EU go in the Arctic?

Member States generally inscribe their Arctic policies within the broader EU policies such as the Green Deal or the EU Maritime Security Strategy. In the policies, the fight against climate change, environmental protection, fisheries (notably the ratification by the EU of the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries agreement) and research are the key areas where the EU is perceived as most valuable by the MS. The EU brings an added value and allows its (smaller) MS to have more international influence as a champion of multilateralism and the leader in the fight against climate change.

The decrease in references to the EU in the national policies denotes a change in the perception of the EU by MS, from the EU being an important political actor in the governance of the region to the EU as a normative and legislative influencer. Over the years, the EU’s transversal policy-making and normative influence has been internalised in the national Arctic policies. The impact of EU’s policies in the Arctic is portrayed as an added value to the MS. But this evolution occurred in parallel to the EU’s striving to have a growing geopolitical role on the international stage,34) including in the Arctic, and it is precisely this role that is now less mentioned in the policies. It does not necessarily mean that the EU is not a recognised geopolitical Arctic actor anymore. It could suggest that its role in the Arctic is already well established and that there is no need for the MS to repeat it. It could also suggest that it just acknowledges the reality of the EU’s Arctic economic and normative presence.35) However, combined with the observations made during conferences and the interviews, it could also mean that the MS do not want to emphasise a potentially too powerful EU as a geopolitical actor in the Arctic.

The EU is trying to project the image of a unitary geopolitical power in its discourses vis-a-vis the Arctic. Both the sentence “the EU is in the Arctic”and the map (in which the EU appears as a single geographical entity) in the promotion video of the 2021 Joint communication36) tend to put forward a unitary political and geographical entity in the Arctic.37) This influences the way external actors are perceiving it despite the internal multi-actor system.38) However, public performances sometimes contradict this stance. A French diplomat made an interesting observation about the fact that during the Arctic Circle Assembly in October 2022 in Reykjavik, an “Asian dimension” could be observed with panels assembling India, China, Korea, and Japan. There was, however, no similar European panel in the programme, which they explained as coming from the difficulty to have the EU juxtaposed with MS in the same panel. The risk, according to them, was to see the MS putting forward their own national strategies instead of bringing something to the European dimension.39) There have been panels in other conferences with both EU representatives and MS representatives, but the mere fact that this fear exists suggests that the EU and the MS can overshadow each other even though it theoretically should not be the case. France’s explicit choice to distance itself from the geographical argument put forward by the EU is logical from a purely narrow French perspective, however it undermines the European scale of the EU’s (i.e. the institutions and its MS) actions and policies in the Arctic and reduces the EU to its institutions or to an abstract entity.

The EU Arctic policy does not transform the common interests shared by the EU and its MS into a coordinated political narrative at the European scale or in an agreement on the (geo)political role that the EU should have in Arctic governance. When asked how Estonia sees the complementarity between being an EU MS and applying to be an observer to the AC, a representative answered: “actually, some EU Member States are already represented at the AC anyway, so the EU is sort of partly behind the table. And it has so many resources and is so powerful that they don’t desperately need to be behind this table as Estonia needs to be, we are not that big and powerful.”40) The European scale – the EU’s size and power – can sometimes make it appear as a threat or a competitor in the Arctic for its Nordic MS rather than an added value and coordination body: “It’s a delicate balance inside the Arctic 8, it’s not only Russia but also other countries that might fear that the EU is maybe too big…”.41) A Finnish diplomat comments: “sometimes those seven member states of the AC are not too keen on having the EU come in and having the EU as a policymaking body. They rather have all the money that the EU can give.” 42) Despite one of the EU’s priorities being to contribute to a “peaceful Arctic”, Denmark was also wary of the fact that the EU might import tensions with Russia in the AC, especially with Eastern European and Baltic states,43) and is very much against the idea of internal coordination on polar matters to avoid giving the impression of having a mandate before an AC meeting. Thus, the room for more political coordination at the EU level is also limited from the inside. This is well summarised by one EU representative: “I have the feeling that the three of them [Denmark, Finland, and Sweden], despite supporting the EU’s Arctic policy, do not really want more EU political engagement or role in the Arctic governance. It is their backyard”.44)

Even for a strong advocate of more EU-Arctic interrelations such as Finland, there is a red line to the EU geopolitical action in the Arctic: “Russia, and the US and Canada would not accept that [the full membership of the EU to the AC], Denmark probably would not accept that because Greenland is not part of the EU and it leaves Finland and Sweden… I don’t think that we [Finland] would accept that either.”45) Whether the EU needs to be more included in the AC to exert geopolitical influence in the Arctic is another question. The question here is whether there is even a real will by the MS for the EU to have an increased geopolitical role and what this role would entail. The AC remains a very state-centred structure, which is itself the result of long negotiations and compromises46) and none of its members is open to change its current structure to consider the geographical position and legal power of the EU.

Conclusion

The analysis of the interplay between European national Arctic policies and the EU Arctic policy helps to shed light on the EU’s leeway in the Arctic. The overview of the national Arctic policies unveils a will by the MS for a stronger role at the EU level in selected areas (research programmes and funding, sustainable regional development, and fisheries) but also the different ways in which the MS articulate their policy with the EU’s policy. Moreover, combined with interviews and observations on the ground, discrepancies between the policy and political levels appear, beyond the generally broad support for “more EU in the Arctic and more Arctic in the EU”.

Thus far, the EU Arctic policy fails to give a European political dimension to its Arctic policy that would provide guidelines to the EU institutions and its MS to create geopolitical unity at the European scale. This situation makes it appear as representing the interests of the EU institutions as if they were distinct from the MS. Thus, what is understood as the EU and what its “geopolitical role” means varies also among the MS. The willingness to accept an EU geopolitical role in the Arctic remains dependent on how the state is envisioning its role in the Arctic and in the EU, and on whether the EU is perceived as an advantage or a drawback. This might not come as a surprise for any EU specialist but is worth remembering when commentating on its Arctic policy and geopolitical actorness. The EU’s “geopolitical role” in its traditional meaning47) whilst being supported globally by the MS, has its limitations in the Arctic because it is seen as a potential destabilization to the delicate balance of powers created over the years in the AC. In the Arctic, but this might also be true elsewhere, whilst the EU is learning the language of power,48) this language does not seem to be the one that will allow a stronger geopolitical role. On the contrary, so far, it seems to be jeopardising its chances to have a more active role in Arctic governance institutions.

Emilie Canova is a PhD candidate in Geography and Polar studies at the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge University.

References