The European Union in Antarctica: An Emerging Area of Interest?

Over the past decade, the European Union has not only developed broader interests in the Arctic region but also regarding the Arctic’s geographical opposite – Antarctica. Photo: Alamy Stock Photo

The European Union (EU) is increasingly not only looking north, to the Arctic, but also south, to its polar opposite. The Antarctic is emerging as an area of interest in Brussels, albeit amongst a few key decision-makers and with a rather specialised focus.

Here at The Arctic Institute we have written extensively about the EU’s quest for a coherent (and recognised) Arctic role and policy. Despite several setbacks, these steps have been largely successful in the Arctic, and the EU has become an accepted partner at the Arctic governance table.

More recently, the EU – or certain limited parts of the EU-system – has become increasingly engaged in Antarctic matters. Naturally, there is little point in comparing the two polar regions. First and foremost, Antarctica is a continent, with most of its territory falling within the Antarctic Circle. Legally, the spatial extent of the Antarctic regime is specified by the Antarctic Treaty, which defines its operational area to be south of 60°S. Furthermore, unlike the Arctic, the Antarctic has no history of supporting human populations, and no Indigenous peoples. Basically, whereas the Arctic is an ocean surrounded by sovereign countries, Antarctica is a landmass not officially belonging to any country, surrounded by oceans.

Developing an EU interest

The Antarctic region and issues pertaining to it – particularly research, climate awareness and ocean governance – have slowly emerged on the policy agenda in Brussels in recent years. Moreover, as both EU citizens and Member States are involved in various activities in Antarctica, broader EU involvement may not be so unreasonable. In a recently published journal article with the European Foreign Affairs Review, we examine this development in-depth. Here, we will outline the main points in that work

Briefly put, first, EU policies directly affecting Antarctica are largely promoted and decided by a few Member States with specific Antarctic interests. Those that claim territory in Antarctica are the starting points for our enquiry. Second, initiatives such as the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPA) derive from specific interests amongst certain actors in the EU system who deem it advantageous to pursue them through related policies. Third, policies are the outcome of intra-institutional goals and strategies in the EU system aimed at signalling environmental leadership to EUropean and international audiences.

For more on the background of the EU’s Antarctic initiatives and its legal and institutional Antarctic set-up, we refer to our article entitled The EU in Antarctica: An Emerging Area of Interest, or Playing to the (Environmental) Gallery?

Doing good, far from home? – MPAs in Antarctica

One particular part of the EU’s Antarctic interest that has spurred recent engagement is the effort to establish new maritime protected areas (MPAs) in waters off the Antarctic continent. MPAs arose as a concept for the protection of certain sensitive maritime domains, although at its core an ‘MPA is nothing more than a particular management strategy applied in a defined area’.1) However, since the early 2000s, this particular form of ocean management has become a staple of many countries’ attempts at improving zonal regulations and the governance of ocean areas.

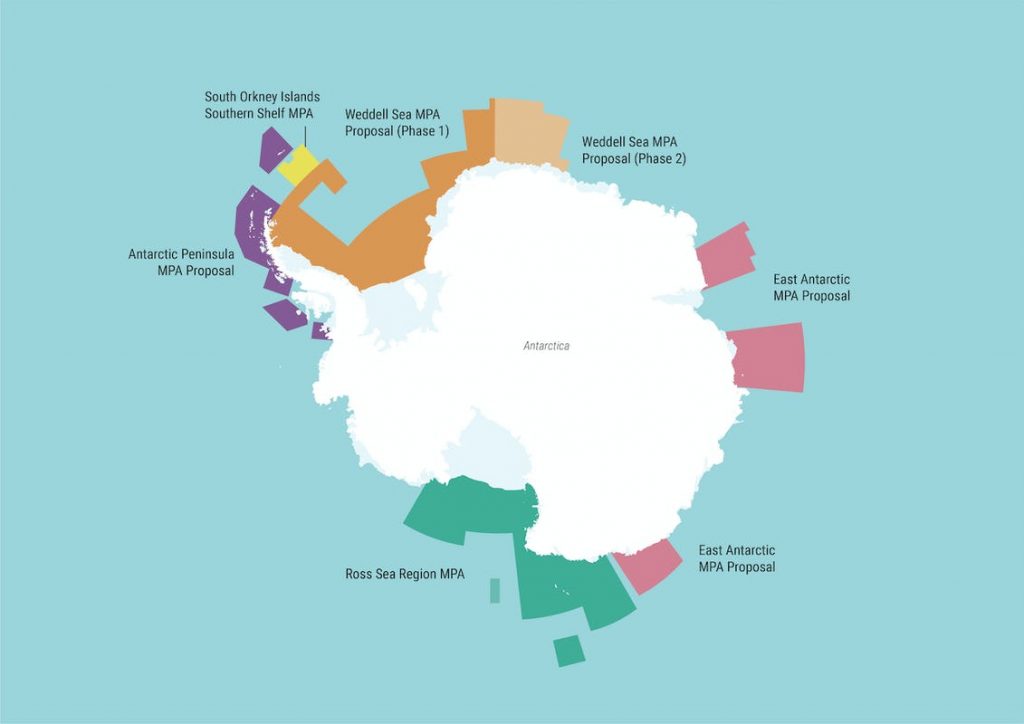

In the Antarctic, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) was established with the objective of conserving marine life, and in response to increasing commercial interest in Antarctic krill resources and the history of over-exploitation of several other marine resources in the Southern Ocean.2) Today, CCAMLR has twenty-six members, including the EU. Starting in 2009, the UK proposed a South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf MPA to CCAMLR.3) Although parts of it to the north had to be removed, it met little opposition amongst the members. Establishing this MPA was seen as the first step in a larger connected effort to establish a series of MPAs across Antarctic waters, following the more general UN recommendations on MPAs.

In 2011, New Zealand and the United States proposed another MPA in the Ross Sea.4) At the same time, proposals for the East Antarctic and the Weddell Sea were being deliberated. Concerning East Antarctica, Australia, France and the EU took the initiative,5) whereas the EU and the UK were developing a proposal regarding the Weddell Sea.6) The resultant Weddell Sea MPA covers 1.8 million square kilometres in a remote, ice-covered part east of the Antarctic Peninsula. These suggestions met with fierce resistance, especially from China and Russia,7) concerning possible limitations on local fisheries – prompting the question of ‘whether national economic incentives in the Southern Ocean are now overwhelming science and conservation values’.8)

In 2016, after five consecutive years of China and Russia blocking the proposal,9) the members of CCAMLR finally agreed on the Ross Sea MPA, which entered into effect in December 2017. At 1.55 million km2, it has been hailed as the world’s largest MPA, although, as put by Rothwell: ‘the length of time taken to reach consensus on the proposal highlighted differences of views amongst member states and it remains to be seen whether CCAMLR members will be supportive of similar initiatives in other parts of the Southern Ocean’.10) The East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea proposals, however, have still not been affirmed, despite continued efforts by the proposers to reach a joint agreement. In addition, other parts of Antarctic waters, like the Antarctic Peninsula region, are under consideration for the establishment of MPAs.

It seems clear that the issue of establishing MPAs is not only an important dimension regarding the EU’s Antarctic involvement, but also one that prompts further EU engagement with the southern region. However, this seems to relate to the engagement of one specific unit within DG Mare only, which links the establishment of Antarctic MPAs with the EU’s global targets of having 10% of marine areas protected by 2020. Antarctica is seen as one area that could help the EU to achieve its 10% target by implementing large MPAs in waters where there is little or no economic activity, and thus few objecting interests.

The Future of EU’s Antarctic Endeavour

As yet, Antarctica – the world’s southernmost continent – has not necessarily come to the fore of EU policymaker agendas; with a few exceptions, broader environmental considerations, research efforts and economic activities have occasionally led EUropeans to look southwards. This is not only because of the continent’s low visibility in global politics and the lack of a ‘proper’ international crisis in and around the region, but also has an inherent EU-internal aspect: the tendency of some Member States to guard what they consider their sovereign domain.11)

Our study has shown that, regarding Antarctica, the EU’s approach is not driven by one coherent approach or framework, but is dominated by limited issue-engagement in a domain where benefits – at least symbolic ones – can be reaped. With limited fisheries activity and little interest beyond national research initiatives, action on MPAs has become an area where the EU can maintain its image as a forerunner in environmental policies – even though these waters are probably the farthest from EUropean waters as is possible to go.

On the one hand, Member States and their fishers are keen to exploit economic opportunities, no matter how relatively minor in comparison with fisheries elsewhere or other economic activities. On the other hand, the Commission/EEAS actively promote the principles of sustainable management and precaution regarding marine living resources. Thus, the two positions that ‘the EU’ holds here – one specific and one general – contradict each other and reveal the EU’s multi-headed nature on issues such as these.

Despite the EU’s insistence and relatively concurrent push for the MPA issue around Antarctica, other actors – notably China, Russia and to some extent Norway – have been sceptical about the creation of new protected areas. Not only do differences in regulatory and management approaches enter the picture (as in the case of Norway): also, economic interests and geopolitical rivalries have become more pronounced on this issue in recent years.

Here the EU also finds itself embroiled in a (geo)political rivalry focused on Antarctica, where the clash of interests – economic vs. environmental – seems set to increase. Moreover, the Commission has expressed a desire to advance the EU’s geopolitical role in effect balancing against the decisions taken in Moscow, Beijing and even Washington, DC. With the emphasis on a so-called ‘Geopolitical Commission’, EU engagement in environmental affairs in Antarctica might also rise higher on Brussels’ agenda, albeit from a very low starting point.

References