The EU and the Arctic: A Never Ending Story

Deputy Secretary General of the EU Foreign (EEAS) Helga Schmid visiting Svalbard with Kåre R. Aas. Photo: Alex Winther, UD

The European Commission’s new outline for an EU Arctic policy, released at the end of June, goes a long way in showing how the EU wishes to be perceived as a serious and balanced Arctic actor. Other parts of the EU-system, however, have taken a different approach throughout the summer months. Using the kind of simplified Arctic-rhetoric that has caused many problems for the EU in the past, some Members of the European Parliament have yet again called for an Arctic drilling moratorium and questioned the region’s governance structures. The ongoing oil and gas debate in the European Parliament highlights how the EU is not, at least yet, a coherent actor on this issue, and is still in the early stages of developing its own comprehensive Arctic Policy.

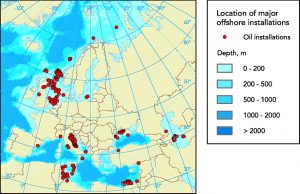

In a summer when Shell started drilling in the Chukchi Sea, Greenpeace activists hijacked a rig in Russia, and a shifting oil rig in the Barents Sea caused alarm in Norway, Arctic oil and gas has most definitely been on the agenda, both in and outside of the Arctic.1) Certain members of the European Parliament have consequently used the Commission’s proposal on new safety rules for offshore oil and gas as an opportunity to address issues concerning such activities. As before, however, some of the proposals in the Parliament highlight a greater desire to be seen doing something about the Arctic rather than actually understanding the matter at hand.

An Improved Outline for an EU Arctic Policy

After a long wait (the European Commission’s first and only Arctic communication came in 2008) and numerous delays (the follow-up was initially due in June 2011), the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and the European Commission jointly published its ‘Arctic Policy 2.0’ in late June this year. As already outlined in a previous article by Andreas Raspotnik and Kathrin Keil, the communication sets out multiple goals for EU-participation in the region, while also reinforcing its objective to take part in regional cooperation (read Arctic Council).2)

The communication itself is a balanced and concrete statement, making headway towards a policy that comprises more than just overarching concepts and ideals. In many of the paragraphs, the Commission actually points to specific contributions that the EU is already making, or could possibly make in the future, as the Arctic continues to become a region of global interest. Especially interregional cooperation and research in the European parts of the Arctic stands out. It therefore makes a significant contribution to addressing the outspoken negativity towards the EU from some of the Arctic littoral states, although a lot of progress still remains to be done. As Raspotnik and Keil highlight, “the Communication clearly shows the EU’s unwillingness to step on the toes of any of the Arctic states by remaining largely unspecific, pushing back against the perception of the EU as a “super-regulator” and concentrating on environmental, climate change and research issues, supporting any effort to ensure the effective stewardship of the Arctic environment.”3)

Offshore Oil and Gas Safety and the Arctic

In parallel to the publication of this Arctic policy statement, the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers have been addressing the Commissioner for Energy Günther Oettinger’s proposal to create a mandatory, EU-wide set of rules for offshore oil and gas safety.4) The Commission’s proposal, developed as a consequence of the 2010 Macondo accident, sets out a grandiose plan in the form of a regulation that would basically replace national legislation on the matter. Given that only a handful of EU-member states actually produce offshore oil and gas, EU-countries like the United Kingdom, Denmark and EEA-member Norway have been critical of the idea that EU-wide regulation is needed. Before Norway ‘decided’ that this proposal would not be relevant for its economic agreement with the EU, it had proposed that the regulation became a directive such that countries would have more leeway in interpretation, in accordance with national legislation.5)

The Commission has also included some brief paragraphs about the Arctic, although this is by no means the main focus of the proposal. Given the EU’s dependence on gas imports from the Arctic part of Russia and the probability that petroleum activities in other parts of the Arctic will increase, the Commission has stated that:

The serious environmental concerns relating to the Arctic waters, a neighbouring marine environment of particular importance for the Community, require special attention to ensure the environmental protection of the Arctic in relation to any offshore activities, including exploration.6)

The Commission shall promote high safety standards for offshore oil and gas operations at international level at appropriate global and regional fora, including those related to Arctic waters.7)

These points, in the context of a comprehensive and detailed proposal, are neither shocking nor particularly new to the EU-Arctic debate; rather, they reflect that the Commission acknowledges the debate concerning Arctic drilling, while also trying to strike a balance between preservation and exploitation.

The European Parliament and the Arctic

The proposal from the Commission seems to have triggered Arctic action amongst some Members of the European Parliament. Taking the proposals stated above, some MEPs in the environment committee suggested calling for a moratorium on Arctic drilling and developing stronger international governance regimes for the region. This was proposed during the summer months, as the committee started its work on the matter and produced amendments to the Commission’s original proposal. Another amendment put forward was that “Member states should not issue drilling licenses for these waters”.8) Seeing that no EU member state has any jurisdiction over Arctic waters, this might be a tricky one to fulfil. Altogether, many of the amendments proposed by the environment committee seem to be aimed at ‘doing something’ about the Arctic, instead of considering the factual realities of the situation and devising appropriate solutions.

As drilling commences in more southern Arctic waters, differentiation between the various parts of the Arctic might be of value to the European debate, especially since many EU member states receive much of their gas from the Arctic territories. Talking about what governance regimes are lacking, and how to amend it, might be another useful contribution. The final vote on these amendments is scheduled for the 19th of September in the environment committee, before the industry and energy committee adopts the final version and passes it over to the full plenary in Strasbourg. In the end, the Council of Ministers will throw in their recommendations, and it is then up to the Commission to draw up a revised version acceptable to all parties. The amendments concerning an Arctic moratorium will most likely shed away long before that stage. They do, however, highlight a lack of cohesion in the EU with regards to the Arctic, and that the EU still has a long way to go before a comprehensive Arctic policy is in place.

No Cohesive EU-position

Looking at the subsequent debates on the proposal in the European Parliament, it is clear that the EU is not one coherent actor on this topic. Media and national politicians alike often brand the EU as such, making it easier to attack different statements made by different parts of the institutional set-up. Last year’s debate around the Spitsbergen Treaty is an excellent example, where one out of 754 MEPs in the European Parliament raised questions concerning the legality of the Treaty, and suddenly Norwegian media exclaimed that the ‘EU’ was questioning Norwegian sovereignty in the region.9)

The development of an EU Arctic policy is still in its infancy. What path to take, which rhetoric to use, and what the emphasis should be on, is an institutional battle between different sets of interests. The Commission would, as part of their job description, like to promote the EU’s global role and natural inclusion in forums like the Arctic Council. Parts of the European Parliament, especially the Green party, are more concerned with the environmental aspects of Arctic activities. And the opinions of the Council of Ministers represent a diplomatic trade-off between those protecting their Arctic interests (Denmark), those in favour of a strong environmental focus (Germany and Sweden), and those who couldn’t care less about the Arctic (some of the southern states).

The Commission’s new communication is by all means a step in the right direction. Consequently, it is incumbent upon states like Canada, Russia, the U.S., Denmark and Norway to acknowledge this improvement and find ways for an inclusion of the EU that benefits all parties. The rhetoric used by some in the European Parliament additionally highlights opposing interests within the EU, and suggests that the EU still has some way to go before agreement on a common policy for the region. In the meantime, communication, knowledge-building and discussion about the region should have primacy.

References