Environmental Détente: What can we learn from the Cold War to manage today’s Arctic Tensions and Climate Crisis?

NASA scientists collect water samples to examine chemistry and plankton in the Arctic Ocean, 2011. Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Much recent discussion has focused on the contemporary militarization of Arctic and subarctic regions. Journalism and scholarship alike question if military conflict might occur, how peace can be maintained, and what war would look like in the Arctic. To provide insight on such queries, The Arctic Institute’s 2021 Conflict Series provides analysis on past Arctic militarization and military activities—seeking both historic context and lessons learned for modern Arctic politics.

The Arctic Institute Conflict Series 2021

- The History and Future of Arctic State Conflict: The Arctic Institute Conflict Series

- Fisheries Disputes: The Real Potential for Arctic Conflict

- Environmental Détente: What can we learn from the Cold War to manage today’s Arctic Tensions and Climate Crisis?

- Knowledge is Power: Greenland, Great Powers, and Lessons from the Second World War

- The Impact of the Post-Arms Control Context and Great Power Competition in the Arctic

- The Arctic Institute Conflict Series: Conclusion

The past year has seen an unprecedented rise in U.S.-Russia tensions in the Arctic since the end of the Cold War. For the first time since the 1980s, NATO warships entered the Barents Sea just off Russia’s Arctic coast in May 2020. A few months later, the Russian Navy conducted military exercises in the Bering Sea, startling a group of Alaskan fishermen.1)

As the region faces such military activity, and the great powers grow increasingly suspicious of each other’s Arctic ambitions, what can we learn from the Cold War to maintain peace and security in the Far North? With a new administration in the White House, and Russia chairing the Arctic Council, it is a good time to examine the prospects for improving U.S.-Russia relations concerning our greatest mutual security threat, the climate crisis.

Scientific Cooperation

The Arctic has long been described as a unique region of peace and cooperation, especially in the field of scientific discovery. One of the earliest examples of East-West scientific dialogue is the correspondence between polymaths Benjamin Franklin and Mikhail Lomonosov, in which Franklin asked his Russian counterpart for “an account of the discoveries of the Polar voyage” in 1765.2)

In the post-World War II period, U.S.-U.S.S.R. Arctic science collaboration had largely been suspended until the 1957-1958 International Geophysical Year (IGY). The IGY was a global science initiative inspired by the nineteenth-century Austro-Hungarian explorer Karl Weyprecht, a staunch advocate of international Arctic expeditions. “When countries that consider themselves to be advanced in terms of scientific progress decide to work together, [they] completely eliminate any national competition,” wrote Weyprecht in 1875.3) As though speaking to us in the present, this holds as a lesson for today.

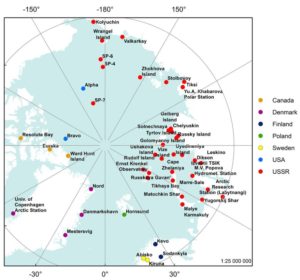

It wasn’t until Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 that the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union agreed to join the IGY program, opening the door to several significant collaborations with the U.S. and other participating countries. 67 nations took part in the IGY, including Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden. In the Arctic, over 40 IGY research stations were installed to study weather at high latitudes, the movements of sea ice, and radio interference induced by aurorae borealis bursts.

Moreover, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. agreed to manage and fund two World Data Centers for the IGY. The new institutions compiled an unprecedented amount of data in the form of datasheets, tables, charts, and maps on kilometers of photo and film. Today, there are 50 such centers in 12 countries.4) The IGY enabled the international scientific community to better understand polar oceanography, glaciology, and meteorology.

Such scientific exchanges became possible during the Khrushchev Thaw in part due to the advocacy of renowned Soviet scientists who had worked abroad, such as Igor Tamm and Sergey Kapitsa. The Khrushchev Thaw saw repression and censorship relaxed in the USSR. Some scientists were exposed to Western views in private screenings of the apocalyptic films On the Beach and Dr. Strangelove, which highlighted the existential threat of nuclear war. It was during this period that scientific views moved away from confrontation towards cooperation, first in nuclear issues and then in larger empiricism.5)

The End of the Cold War

Before the late 1980s, scientific cooperation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union had been limited. The U.S.-U.S.S.R. Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Environmental Protection of 1972, with specific reference to Arctic and sub-Arctic ecosystems, had gained interest among the Soviet political elite, but it wasn’t until Mikhail Gorbachev came to power that the Arctic witnessed a new era of rapprochement regarding cooperation on non-military challenges such as environmental degradation.6)

The final years of the Cold War coincided with a greater emphasis on recognizing mutual interests related to protecting the environment. Gorbachev’s election concurred with a wave of reforms and a “new political thinking” on foreign relations. One example was the incorporation of environmental issues into international affairs. President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev called for a joint report on climate change after the 1986 Reykjavik summit. The official joint statement following the 1988 Moscow summit devoted special attention to Arctic cooperation:

“Taking into account the unique environmental, demographic and other characteristics of the Arctic, the two leaders reaffirmed their support for expanded bilateral and regional contacts and cooperation in this area. They noted plans and opportunities for increased scientific and environmental cooperation under a number of bilateral agreements as well as within an International Arctic Science Committee of states with interests in the region. They expressed their support for increased people-to-people contacts between the native peoples of Alaska and the Soviet North.”7)

The findings of the 1990 publication that came out of the U.S.-U.S.S.R. study, “Prospects for Future Climate,” even hold up well today. The environmental bilateral dialogue also produced an understanding of the ecological consequences of a “nuclear winter.” It was warned that unrestrained military buildup could lead to a global environmental collapse with no winner.8)

In his famous 1987 Murmansk speech that ultimately inspired the creation of the Arctic Council, Gorbachev declared that “the Soviet Union was in favor of radically lowering the level of military confrontation in the region,” and put forward a list of proposed policies to turn the Far North into a zone of international collaboration. Gorbachev praised the exceptional detachment of Arctic environmental protection and sustainable development from global political dynamics.

Managing today’s tensions

The spirit of Arctic exceptionalism and Cold War examples of scientific cooperation offer effective models for improving relations and strengthening soft security despite tensions. In the twenty-first century, one of the noteworthy examples of East-West scientific cooperation is the Russian-American Long-term Census of the Arctic (RUSALCA, which means mermaid in Russian). The project emerged out of a Memorandum of Understanding between the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS). Across several expeditions to the Bering and Chukchi Seas between 2004 and 2015, Russian and American scientists made major joint contributions that help us understand the marine chemistry, glaciology, oceanography, and ecosystems of the evolving Arctic.9)

“The cooperation between Soviet and Western Arctic scientists turned out to be of considerable practical and symbolic value, and it spilled over into the political and military spheres,” writes Kristian Åtland.10) Even at the height of the Cold War and despite the ideological differences, Reagan and Gorbachev embraced the wisdom of engaging in areas of cooperation, rather than isolating the other.11) In this spirit, the RUSALCA project should be reengaged and reinforced. Russian ice-breaking capabilities, which enable expeditions in sea-ice covered areas, vastly outweigh U.S. capabilities. Therefore, collaboration and the sharing of resources and data are crucial to advancing our understanding of the environmental and biological changes in the Arctic.

Thawing permafrost and extreme weather in Russia have prompted President Putin to pay attention to climate change.12) The Biden administration has identified climate change as a key priority in its Arctic policy. In December 2020, 193 U.S.-based Arctic scientists signed an open letter to the Biden administration asking that they appoint an Arctic Ambassador to the Arctic Council “to repair frayed U.S. diplomatic ties [and] express renewed U.S. commitment to address climate change in the Arctic and everywhere through intensified cooperation.”13) There are similar outlooks in Russia.

“Geopolitical and environmental processes are seemingly far apart, but they exist shoulder to shoulder in the Arctic region… Rivalry should not hinder the joint work of scientists from different countries of the world. Collaboration with scientists from all over the world allows us to conduct comprehensive research and draw more accurate conclusions,” said Alexander Sergeev, President of the Russian Academy of Sciences.14) Arctic scholars Oleg Anisimov, Kelsey Nyland, Robert Orttung, and Alexander Sergunin likewise call on the U.S. and Russian governments to promote scientific collaboration within the frameworks of the Arctic Council and the 2017 Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation.15)

There is substantial and ongoing support in the international scientific community for Moscow and Washington to find a common understanding in tackling the climate crisis. The Arctic, warming at nearly three times the global average, should be the first place of attention. Scientific cooperation, an essential endeavor for the world’s survival, may likewise build trust and prevent a conflict in a region that has not seen interstate violence in almost a century.

References