Crabtacular! Snow Crabs on their March from Svalbard to Brussels

A fisher takes snow crabs on board. Photo: Jonas Selim, Forsvaret

For some years now, Norway and the European Union have exchanged diplomatic ‘pleasantries’ and engaged in a dispute over a new Arctic resource: snow crab.

Although already discovered in the Barents Sea in 1996, Norwegian fishermen only started catching snow crab to a considerable extent on the Norwegian continental shelf in 2013. Snow crab fisheries was quickly heralded as the new Arctic gold, potentially even rivaling cod fisheries in value. Thus, it is no surprise that fishermen from Norway, Russia, and EU countries like Latvia and Poland were quickly investing in equipment to expand their fishing operations in both Russian and Norwegian waters.

As relations between Russia and ‘the West’ deteriorated in 2014, Russia decided to close its continental shelf for foreign crab fishing. EU-crab fishers thus turned their ‘hungry eyes’ to the ‘Loophole’, a small area of international waters between Norway and Russia in the Barents Sea, as well as the continental shelf around the Svalbard archipelago. Norway, however, decided to ban snow crab fisheries starting in 2015, awaiting more research on this new species and the creation of a management plan for the Barents Sea. Yet, at the same time, it allotted limited licenses to its own fishermen in order to not squash this new industry in its infancy.

What legal regime governs snow crab fisheries?

The EU’s fishermen turned to the Loophole arguing that under the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) unregulated stocks can be freely caught by NEAFC members. Yet, it quickly became clear that both Norway and the EU define snow crab as a sedentary species, meaning it is “unable to move except in constant physical contact with the seabed or its subsoil” (Art. 77, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)). In non-legal gibberish: it does not swim but marches on the seabed. Thus, Norway argued, snow crab fisheries are not regulated under NEAFC but instead fall under UNCLOS’ regime for sedentary resources. In 2009, Norway acquired an extension of its continental shelf that also included most of the Loophole, bringing foreign crab fisheries in this area under Norwegian jurisdiction. EU-fishermen, however, disagreed.

In late 2016, the dispute escalated when the Norwegian Coast Guard arrested the Latvian-licensed (and Lithuanian-owned) vessel Juros Vilkas for operating in the Loophole without a Norwegian license. The case ended at the Norwegian Supreme Court, which ruled that Norway – in accordance with UNCLOS – has complete sovereignty over resources on its continental shelf. The EU – through the Commission’s Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, which manages the EU’s fisheries policy – had already recognized this in 2015 and accordingly communicated that Norway had sovereignty to its member states.

The controversy surrounding Svalbard

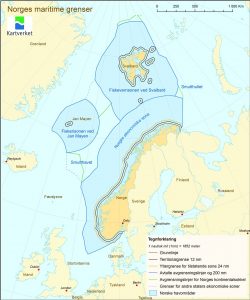

What makes the snow crab case even more controversial is that Chionoecetes opilio (the scientific name for snow crab) has chosen the waters around Svalbard as its new home. In 1977 Norway established a Fisheries Protection Zone around the archipelago, arguing that Svalbard’s maritime zone and the continental shelf are part of the Norwegian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the Norwegian continental shelf because the Treaty of Spitsbergen from 1920 infers sovereignty over Svalbard to Norway. Yet Norway avoided establishing an outright EEZ, instead opting for ’only’ protecting marine species in this zone and thus avoiding stark opposition by other signatories of the Treaty.

Some of these states, however, which are currently 44 in total, claim that although Norway has jurisdiction in the maritime areas around Svalbard, the Treaty’s principles of equal access to economic activity on the archipelago should also apply to the 200 nautical mile zone and the continental shelf. Since 1977, the EU – through the Commission as well as several of its member states that are signatories to the Treaty – has on several occasions voiced this position, diverging from the Norwegian standpoint that the Treaty only applies to the islands of the archipelago.

Agree to disagree

The Svalbard dispute has, however, been kept out of the limelight. It does not figure prominently (or even sometimes at all) in the Union’s Arctic policy documents that have been issued since 2008. Neither does it figure prominently in Norway-EU bilateral relations. Svalbard has become a topic where the EU (and some of its members) agree to disagree with Norway, as long as EU-fishermen have access to limited fisheries based on historic records, and Norway does not discriminate between Norwegian and EU vessels when it enforces its regulatory regime.

But the ban on catching a new sedentary resource – snow crab – introduced by Norway in 2015 brought the two diverging positions to the forefront of (fisheries) relations between Norway and the EU. Albeit of limited economic importance to both EU member states and Norwegian fishermen, the prospects of a new profitable resource together with the disagreement over Svalbard’s continental shelf drew attention to the dispute.

Demanding equal treatment

It is particularly the special treatment of Norwegian fishermen that lies at the heart of the dispute. If the continental shelf around Svalbard is similar to a Norwegian EEZ, Norway has exclusive rights to the resources and can thus award licenses/quotas to whomever it likes. However, if the Spitsbergen Treaty does apply, Norway cannot discriminate against vessels from signatory states, irrespective of whether it has the authority to award licenses.

The common solution to disputes such as these is the swapping of quotas. Offers to swap snow crab quotas were first presented by Norway in November 2015. The EU rejected the offer claiming it had no available means of payment (i.e. no swappable fishing quotas). Albeit continuing informal negotiations, no agreement has since materialized. The Commission, nevertheless, proposed to authorize up to 20 vessels to catch snow crab; a proposal that was accepted by the Council of the European Union (‘Council’), which eventually gave five member states – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Spain – the right to issue 20 licenses altogether in 2017 (the Commission and the Council decide, the member states issue the actual license).

– Not a single crab

Norway reacted to the decision by issuing public statements, with the Norwegian Minister of Fisheries stating in early 2017 that Norway would not “give away a single crab”. Shortly thereafter, the Norwegian Coast Guard arrested another EU-vessel, the only one that had made use of the licenses – the Senator from Latvia. According to Latvian politicians, this led to severe economic losses for the concerned ship-owners, who argued that EU were losing an average of EUR 1 million per month. Eventually, the Council again awarded licenses for 20 vessels, divided among the same states, for 2018. This was done to uphold the EU’s position concerning both the snow crab dispute and its position on the legal status of Svalbard.

Who is driving the EU’s position?

Both in- and outside Europe, the EU is often – purposely or not – misunderstood or simplified as being a ‘single actor with a single voice’. But how should we understand the ‘EU’ in this case and its push to award licenses which were in direct violation of Norway’s jurisdiction of Svalbard’s maritime zones?

What might be perceived by some journalists as a Brussels-based initiative was in fact initially driven by very specific interest groups in a few countries – Latvia and Poland in particular. These interests were concerned with the eviction from the Russian continental shelf and a slowly but steadily growing snow crab fishing industry. These interests managed to find some key actors to speak on their behalf, such as Jarosław Wałęsa, a Polish Member of the European Parliament (MEP).

As the snow crab dispute was first raised in Brussels in late 2015, certain member states have actively lobbied the Commission to ensure their interests were represented. Together with some MEPs, they saw it in their interest to bring the issue to the forefront of Norwegian–EU fisheries relations. But in doing so, it complicated the workings of the Commission that had been trying to find a suitable solution with Norway on fisheries. Moreover, the Norwegian Minister of Fisheries got involved in a case where it is relatively easy to be ‘standing up for’ local fishermen. Being considered as the protector of your own fisheries’ industry can work wonders for your political appeal. Under these conditions efforts to resolve the controversies had reached an impasse by late 2017.

Where to now?

While the EU ostensibly speaks with one voice on fishery-related issues, that voice can be hijacked by special interests, not least when there are few counter-positions and – as in this case – the issue is essentially of limited importance to the Union at large. Moreover, before the snow crab dispute received popular attention and positions became entrenched, there seems to have been a window for dialogue between Norway and the EU. Given Norway’s sensitivity to debates over Svalbard and opposing legal views, it might have been fruitful to engage directly with the Union’s member states to prevent the dispute ascending ever higher on the EU agenda.

At the same time, this limited dispute over snow crab fisheries has still been kept separate as an issue pertaining to fisheries. From 2007/08 onwards, the EU has engaged in Arctic affairs. At times, Svalbard as well as other larger governance questions have arisen, especially in the European Parliament. The snow crab, however, has deliberately been kept as a fisheries question only. Yet some interests in Brussels would still like to see a wider debate on Arctic governance, including Svalbard’s legal status. If no solution on the snow crab issue is found in the near future, this issue linkage might become a reality.

This article was originally published via High North News on 3 April 2018.