"Conquered Modernity": The Soviet Arctic Pavilion at the World’s Fair in 1939

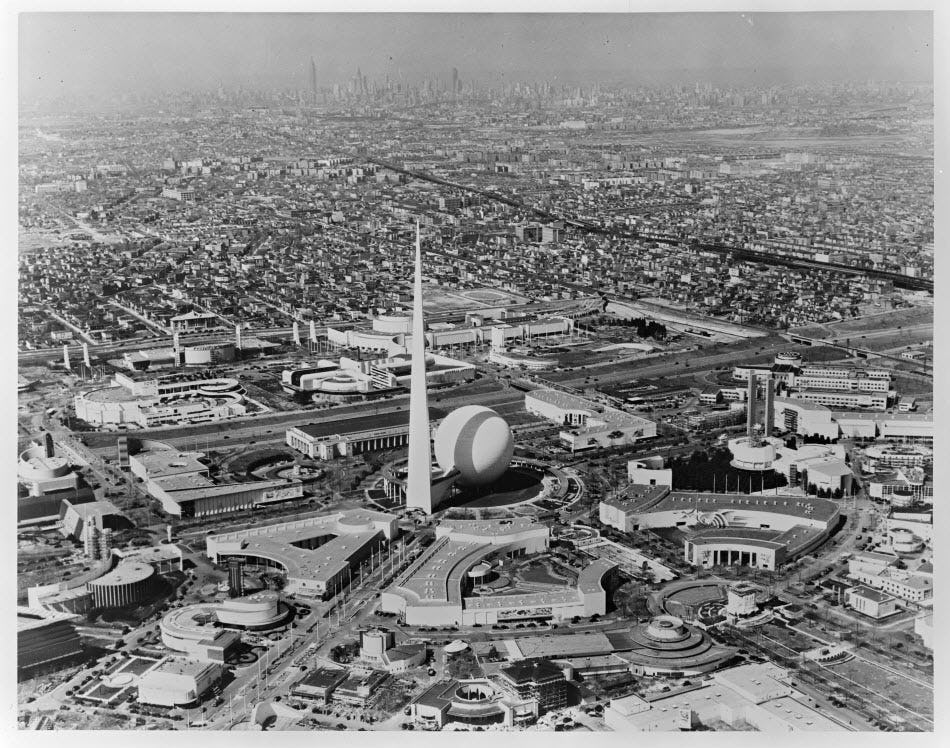

New York 1939 World Fair Aerial View. Photo: NYPL Digital Collections

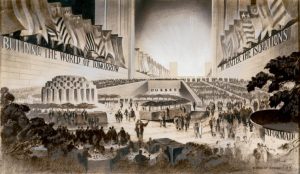

New York World’s Fair 1939-1940 in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park was one of the most significant world exhibitions of the twentieth century and, as John McCannon put it, the “interwar period’s single most elaborate tribute to progress and modernity”.1) Opened on 30th April 1939, just several months before the outbreak of World War II, it vividly reflected the ideological and cultural competition among nations. Under the official motto “Building the World of Tomorrow”, antagonistic visions of modernity and future clashed on the grounds of the Fair as dramatically as on the international arena. And, perhaps, one of the most symbolic embodiments of such visions was the Arctic Pavilion.

The Arctic was granted a special attention at the Fair. One could find it in the so-called “Arctic village” telling about MacGregor’s Arctic expedition 1937-1938, or in the popular Arctic Girl’s Show “Frozen Alive”, which was a huge success and toured around the U.S. after its closing.2) But the most conspicuous display of the Arctic was in fact the Soviet Arctic Pavilion – a peculiar manifest for the triumph of a nation’s technological progress.

For the Soviet Union as a recently emerged state, persistently trying to gain international recognition, the Arctic played a special role. Imagined for a long time as the last blank spot on the map, by the end of the 1930s it finally got “conquered” and “tamed” by the Soviet State, the Soviet Man, and the Soviet Machine. Starting from the mid-twenties, the exploration of the Arctic became a national priority for the USSR.3) During 1937, shortly before the fair, the Soviet Union was the first state to successfully land an airplane on ice, to make a nonstop transpolar flight from Moscow to Vancouver and then to California. The same year, the USSR for the first time in history established a drifting scientific station in the Arctic. In 1938, the famous icebreaker Iosif Stalin was the first one to reach the North Pole.4) Altogether, these sequential events, presented and perceived as heroic, made the Soviet Union famous for its persistent “conquest” of the Arctic and opened up its propagandistic value which was then cleverly used by the Soviet government. In the Arctic, the USSR found a tabula rasa for the implementation of the grand Soviet project.5) And in this regard the Arctic was, perhaps, the only Soviet exhibit which actually fitted into the motto of the Fair: “Soviet explorers, scientists, seamen, aviators and workers have converted the Arctic into a navigable seaway, and are making immense areas within the Arctic Circle habitable”. This discovery rhetoric in regards to the Arctic and the label of “land of tomorrow” exalted the imagination of Soviet engineers, geographers, and writers but at the same time completely ignored the existence and the agency of indigenous peoples of the Russian North, which had dramatic consequences.

One has to note that the Arctic, or rather Arctic indigenous peoples, were not new to the World’s Fairs. According to Benedict Burton, Lapps and Eskimos, for instance, had been represented on at least nine different occasions between the late 19th and early 20th century.6) But following the general criticism towards the issue of “exhibiting dependencies”, which emerged after World War I,7) indigenous peoples and their artefacts were little by little removed from the showcases and replaced by modern machines and technology. The Arctic of the interwar period as well as its representation at the World’s Fair in 1939 was therefore something quite different from earlier exhibitions. Also, despite its relatively rare presence at the World’s Fairs, the Arctic had never been exhibited as a whole entity, or a homogeneous space – on the contrary, there have been many Arctics on display at different times, which is by itself another topic worth looking into.

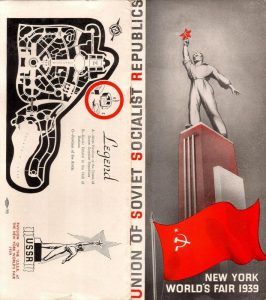

Using the photographic findings from the New York Public Library (NYPL) Digital Collections8) and the information in the official Soviet booklet (cited in italics and provided at the end of this article; courtesy of Mike G. Jurkevic),9) the current article presents a modest attempt to provide an insight into the peculiarities of the display of the Soviet Arctic, and the place and role of the Arctic Pavilion within the exhibition complex of the USSR at the New York World’s Fair in 1939-1940. This could further explain the significance of the Arctic in Soviet imagination and outline the cultural and environmental legacies of those perceptions, which eventually formed Soviet politics in the High North and had a huge impact on the way the Russian Arctic is perceived today.

The Soviet Pavilion Complex in 1939

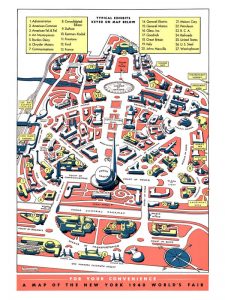

The scale of the USSR’s participation in the Fair was huge, both in spatial and economic terms. The Soviet “World of Tomorrow” was displayed on three different venues: in the Main Soviet Pavilion, at the minor exhibition in the Hall of Nations, and in the Soviet Arctic Pavilion.

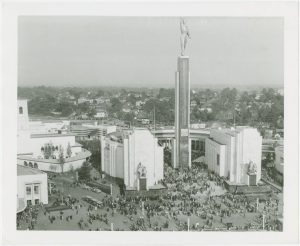

The overall costs reached up to 4 $ billion (in 1930s $) which exceeded even those of the host country.10) But not only the costs were the highest – so was the Main pavilion itself. The statue of a worker on top of the Main Pavilion was the second tallest building at the Fair after the Trylon. What is more, it was higher than the flag on the American pavilion and the statue of George Washington, to whom the Fair was dedicated.

The USSR’s propagandistic message was present everywhere: in the gigantic and monumental architecture, in the choice of expensive construction materials like marble and precious stones, in topics and objects of the exhibitions, and in their descriptions. For example, the commentary on the exhibition on the political and social structure of the Soviet Union in the Hall of Nations claimed that the USSR was “a country which has ended exploitation of men by men, eliminated racial and national animosities and in which 170,000,000 people of different nationalities are united in a voluntary, equal federation of eleven socialist Republics”. This statement fitted well in the context of the first half of 1939.

Throughout the course of the first season of the Fair, the USSR managed to create and maintain a positive image among the audience, and therefore successfully met the main goal of its participation.11) However, it turned out to be a short-term victory – the outbreak of the war brought to naught all Soviet efforts in self-advertising.

In contrast to the American “World of Tomorrow”, represented by innovative projects in engineering, household, and architecture yet to come, the USSR did not present anything strikingly new. Soviet tomorrowland was already there: the displays of the exhibitions told a story about a future, which had already come true and taken shape in the advanced technologies implemented at factories and in the progressive social relations in the contemporary USSR.

This interrelation between the man and the machine was one of the core features of the Soviet self-representation. For the USSR, it was important to stress that it is “not only the development of the machines but also of the people who man the machines” that matters. Numerous models of newly-built factories and electric stations, dioramas, and graphics showing “railways, ships and airplanes, conquering the vast distances of the Soviet union” as well as the huge paintings with smiling people looking above the visitors – all this was made to propagandize the achievements of the Soviet Union and justify its technological and social superiority over the U.S., and make it look truly modern in the eyes of the world.

Persona Grata: The Heroes of the Arctic at the Fair

A few days before the opening, Soviet pilots Vladimir Kokkinaki and Michail Gordienko attempted to make a trans-Atlantic flight over the North Pole with the help of a navigator only. Even though they did not reach the planned destination point, the flight itself got enormous attention of the international community12) and brought them both to the Fair where they met the Fair’s Director Grover Whalen.

Apart from the Arctic Pavilion, the Soviet Arctic was also decoded in some parts of the Main Pavilion. In the lobby, right in the middle of the famous diorama painting called “Outstanding people of the Land of the Soviets” one could see Ivan Papanin in a white suit together with the whole crew of his North Pole-1 expedition of 1937 expedition.13) Also, there were depicted twelve renowned pilots, including Chkalov, Yumashev, and Danilov, as well as Gromov, Baydukov, and Belyakov together with Kokkinaki, all famous world-wide for their transpolar flights in 1936-1939.14)

As mentioned in the booklet, the Arctic also appeared in the copies of numerous articles, from newspapers displayed in the Hall of Science, Literature, and the Press. Besides that, the visitors could have a look at two major publications on the Soviet exploration of the Arctic: “The Conquest of The Arctic” by Otto Schmidt, and Mikhail Gromov’s “Across the North Pole to America” distributed in the pavilions.15)

The Arctic Pavilion

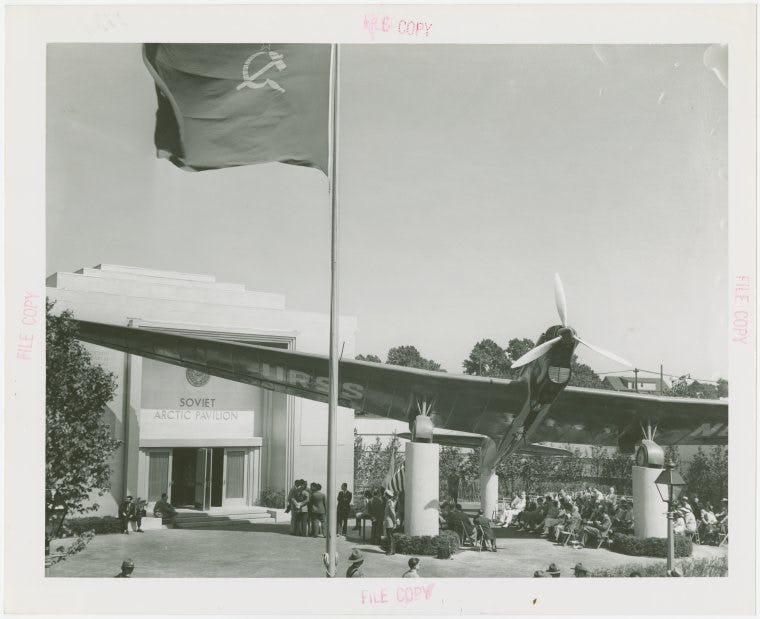

The main attraction within the Soviet pavilion complex was the Soviet Arctic Pavilion. It was constructed to tell the story of the “modern epic of exploration and pioneering” and to illustrate the Soviet victorious conquest of the Arctic. Even though it was not as gigantic and monumental in its architecture as the Main Pavilion, the Arctic Pavilion had some exhibits to impress the audience with.

The Soviet Fair Commission decided to bring objects from two grand Arctic expeditions of 1937, “the banner year of the Soviets in the Arctic”: the Antonov-25 airplane, and the equipment of the renowned Papanin expedition.16) Both were originals. The latter matters especially because it alone already tells a lot about the importance of the chosen exhibits in the eye of the Soviet Commission. And considering the enormous financial expenses on economic and military needs of the Soviet Union at that time, the decision to transport the original parts from the two expeditions is of particular significance in this case.

The ANT-25, exhibited at the fair, was the one used during the record-breaking trans-Atlantic flight from Moscow to Vancouver in Washington state, conducted by Chkalov and his crew in June 1937. The story itself, together with its heroes, was not new for the American public in 1939 – by that time the whole crew was well-known in America, not only thanks to their flight but also because they met Franklin Roosevelt in person and, thus, got widely published in the newspapers.

The fact of placing the ANT-25 right in front of the Pavilion demonstrated an inextricable connection between the Arctic and aviation in the USSR. The Soviet Arctic was impossible to imagine without the Soviet aviation, and vice versa.17) This particular plane model was a well-known experimental aircraft, which had been used for long-distance flights since 1934. So it did not just embody the heroic flight by Chkalov in 1937 but all previous attempts to conquer and claim the Arctic for the USSR. Metaphorically, the ANT-25 was a tool to turn the geographical imagination of the Arctic into reality and put a Soviet stamp on it. There was even no need to go inside the Pavilion to get this idea: the map of the flight painted on the tail and the wording “Stalin’s Route” put all over the left side of the plane were convincing enough for the audience to believe in the Soviet technological superiority in the North.

Unfortunately, little is known about the interior of the pavilion. In the booklet, it only says that “on the ceiling, on an illuminated map, the routes of the historic transpolar flights of Chkalov and Gromov, the recent flight of Kokkinaki from Moscow to America, and the route of the Papanin drift” were displayed. But if exhibiting the plane referred to conquering the Arctic with the Soviet machine, the Papanin expedition – the other major topic of the Arctic Pavilion – reflected on the unshakable will power of the Soviet Man. The expedition was, indeed, remarkable. In May 1937, four planes landed on an ice floe at the North Pole carrying Papanin, Krenkel, Shirshov, and Fedorov, who then for nine months conducted scientific observations on this drifting station.18) The only interior photo from the archives of the New York Public Library shows the Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. Konstantin Umansky, German Tikhomirnov and the famous Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson standing in front of the diorama depicting parts of the equipment, the words “USSR”, and the red star.

The presence of Vilhjalmur Stefansson, “The Prophet of the North”,19) is not exceptional but significant – it stresses the international importance of the Soviet Arctic and the attention it got from the renowned explorers of that time. Stefansson was a popular figure in the Soviet Union and a welcomed guest at the Arctic Pavilion in 1939, where he noted that “we are here to recognize what the whole world recognizes – the unquestioned leadership of the Soviet Union in the field of geographic exploration”.20)

Failed Expectations?

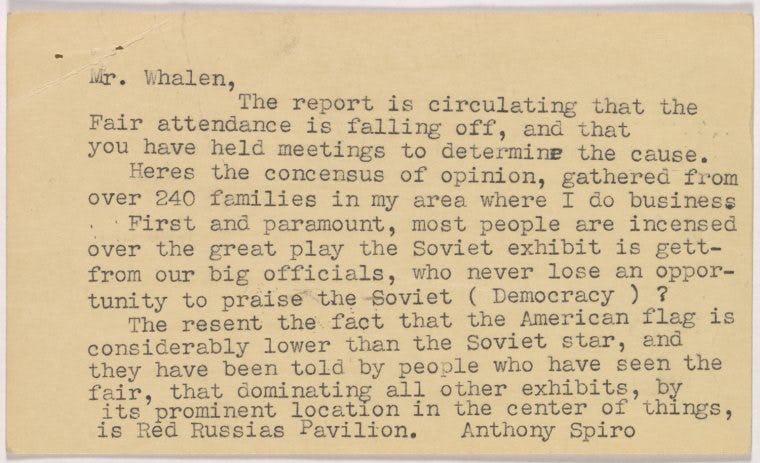

In times of the vulnerable international situation and alarming news coming from the European continent, the USSR went all-in to win the ideological competition at the Fair. No doubt that the Arctic was seen as an ideological “trump card” in this regard. In the eyes of the Soviet Union, the importance and the relevance of the Arctic heroic expeditions and the uniqueness of the original expedition equipment was very high. Keeping in mind the costly efforts of transporting and constructing a separate pavilion for the Arctic, the Soviet Commission definitely expected a high degree of attention.

Indeed, the Soviet pavilions were impressive. But McCannon’s assumption that “much of the credit belonged to the grand display at the Arctic Pavilion” seems to be exaggerated.21) The small number of official photos and the absence of any references to them (found so far) could point to the fact that it was rather of a minor significance for the visitors of the Fair. Anthony Swift, too, mentions that the Arctic Pavilion was actually “sparsely attended”.22) Apparently, there could be several reasons for that. The Arctic Pavilion was located on the outskirts of the Fair, not being really incorporated in the national pavilion complex. In contrast to the monumental structure of the Main Pavilion, it looked more like a warehouse or an airplane shed. Also, despite its spectacularity, the ANT-25 was not the only impressive aircraft at the Fair, and moreover, not shown in action.

Besides, the “Arctic card” might have been useful to play earlier in the 1930s but not so much on the eve of war. The projected success of the Soviet Arctic Pavilion was also diminished by the course of international events and changes in the Soviet foreign policy. In this context, the USSR’s decision to withdraw from the participation at the Fair in 1940 and to demolish the pavilions was significant. In 1940, in its place stood the House of Commons, made to stress the superiority of American democracy. And in terms of the competition on the fairgrounds, it clearly demonstrated Soviet deviation.

Concluding remarks

When drawing assumptions about the significance and the role of the Arctic display, one should keep in mind that most historical resources used so far by such researchers as John McCannon or Anthony Swift are mostly official press releases or letters coming from the archives of Soviet and American governments, which have strong ideological and propagandistic connotation and therefore require certain scrutiny and careful interpretation.

Still, the Soviet Arctic at the New York World’s Fair 1939 was a remarkable event: “however one balances the costs versus the benefits, the airplane, with its promise of promethean uplift (…) contributed indispensably to whatever success the country enjoyed there during the 1930s and afterward”.23) The Arctic was both a symbol of Soviet modernity and technological progress and a daring look into the future, which would see the Soviet Man tame the nature for good with the Soviet Machine. However, despite so many years of gaining international recognition, with the Arctic playing one of the key roles in those efforts, after World War II the Soviet Union would literally have to start from scratch in order to prove its technological and socio-political advancement once again. But at the next World’s Exposition in 1958 in Brussels, the main tool of the USSR’s propaganda would be another exhibit – Sputnik, thus, leaving the narrative of the heroic conquests of the North in the past. Or?

USSR information booklet printed for the World’s Fair in New York in 1939. It contains an elaborate description of the Soviet exhibition complex and its schematic map.

References