The Changing Nature of Russia’s Arctic Presence: A Case Study of Pyramiden

The world’s northernmost Lenin statue looks over the abandoned Russian city of Pyramiden on Svalbard, summer 2018. Photo: Alina Bykova

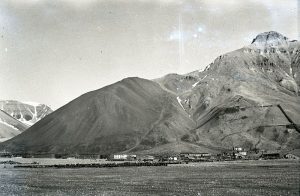

On a frozen island about 1,000 km south of the North Pole stands the world’s northernmost Lenin statue. Vladimir Ilych’s likeness overlooks the Nordenskiold glacier, the frigid Billefjord, and the empty Russian town of Pyramiden. The town, which was once the largest settlement on the Norwegian Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, was abruptly abandoned in 1998. Hein Bjerck, an archeology professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and former heritage officer on Svalbard, remembers how Pyramiden was forsaken just over 20 years ago: “Nobody talked about leaving the place.” Bjerck says. “Each time we came there were fewer and fewer people. Every time there was a boat or helicopter, people left with their small backpacks.”1)

The settlement, one of two managed by Russian state-owned company Trust Arktikugol, went from a population of approximately 1,500 people in the mid-1990s, to a ghost town in the span of several months. Like other companies that managed monocities, Trust Arktikugol was rocked by a financial crisis as the centralized Soviet economy switched to the free market, and it was decided that the firm would not be able to sustain both Pyramiden and Barentsburg (the other Russian town on Svalbard), both of which were heavily subsidized by the government. In 1990 the 2,407 Russians on Svalbard outnumbered the 1,125 Norwegians nearly 2.5 to 1.2) Near the end of the decade, less than a third of the Russians were left, and the population eventually dwindled down to the approximately 500 Russian (and Ukrainian) workers still there today.3)

While the settlements on Svalbard appear to be monocities – single-industry cities whose entire existence is built around the extraction of a resource – they have not been profitable for most of their lifespan. This article will examine how the Russian settlements came to be in the Norwegian Far North and why they are still maintained despite operating at a deficit.

A history of Svalbard and the establishment of Russian settlements on the archipelago

There are two widely used names for Svalbard, a cluster of islands located between a latitude of approximately seventy-four and seventy-eight degrees north. Svalbard means “cold shores” in Norwegian. The second name, more often used in Russia, is “Spitsbergen,” the Dutch word for “sharp mountains.”4) Historically, Svalbard had no Indigenous population, so it is difficult to determine definitively which country established a presence there first. Soviet reports indicate that the Vikings were present there from 1140, and that Russian, Norwegian, and Icelandic people engaged in various activities there since the twelfth century.5) In the fifteenth century, Svalbard was the center-point of regional competition between the English, Dutch, Spanish, French, Danes, Norwegians, Germans, Swedes, and Russians, all of whom whaled and fished in the area.6)

Prior to 1920, Svalbard was internationally recognized as terra nullius, a no-man’s land.7) In the first decade of the 20th century, Norway, Sweden and Russia were in the middle of negotiating a tri-management agreement for the island when the deal was interrupted by World War One and the Russian Civil War. When negotiations resumed in 1918, Norway and Sweden took advantage of Russia’s domestic turbulence and excluded it from the deal.8) The 1920 Svalbard Treaty placed the archipelago under Norwegian sovereignty but gave signatory parties and countries the right to exploit its resources for economic purposes, with the stipulation that the island would never be militarized.9) To this day, some Russians believe that they have been cheated, and that Svalbard should have at least partially belong to their country.

Early 20th century development on Svalbard

In the late 1920s, the Soviet Union bought Pyramiden and Barentsburg, two settlements on Svalbard which were founded by Swedish and Dutch mining companies in the 1910s and 1920s. In the early 1930s, the towns came under the management of the coal mining company Trust Arktikugol, after the Soviet leadership decided to start extracting resources on the archipelago in 1931.10)

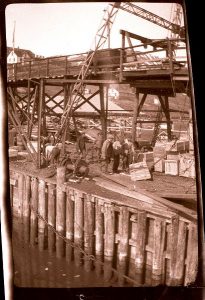

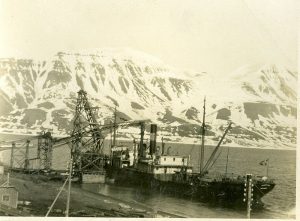

Soviet newspapers of the time, specifically Pravda, describe the settlements and the deyatelnost (production) there in unsurprisingly heroic terms. Issues of Pravda dating between 1934 and 1940 report that coal production quotas were being exceeded every month, that the towns’ populations were growing steadily, and that the workers had organized a choir and orchestra to occupy themselves during the long Arctic winter.11) An article by L. Brontman from 1935 stated that Barentsburg looked like a standard port city, with mountains of coal and cranes near the harbour, massive ships coming and going at all times of day and night, and steady and methodical production no different from Ukraine’s coal-producing Donbass region. Three hundred tons of coal was loaded onto each ship, Brontman wrote, before they left to Murmansk and Arkhangelsk.12)

Pyramiden was named by the Swedes after the triangle shaped mountain behind the town. The mine there was constructed in 1939, but it was not opened until 1956.13)

Svalbard in the postwar years

It is important to note that while the Russian settlements eventually became heavily subsidized and started to serve an entirely political and strategic purpose for the Soviet Union, they were initially developed as purely economic ventures. During the interwar period, Svalbard was not “in the scope of the Soviet Union’s military-strategic considerations,” but served as a major source of coal for Russia’s northern regions.14) In the early decades of the Soviet era, there was no rail connection between the Kola Peninsula and the rest of the country, so the coal shipments from Svalbard fulfilled the important purpose of providing energy to the northern cities in that region.15)

By the latter half of the Soviet period, the settlements (particularly Pyramiden) were designed to be the ideal Soviet utopia, mostly to show the USSR’s power off to the rest of the world, given that the towns were two of the very few Soviet outposts beyond the Iron Curtain.16) While the Norwegians moved around on dog sleds and skis, the Russians had four helicopters on the archipelago. Most of the Norwegian food was flown in, but Pyramiden was well stocked and almost entirely self-sufficient, with livestock for meat and dairy products, a greenhouse where fresh fruits and vegetables were grown, and a factory where garbage was burned and the ash transformed into bricks, which were then used to build some of the newer housing blocs in the settlement.17) There was a cafeteria for workers, complete with a beautiful Soviet-style mosaic of the Arctic, a swimming pool and gym, and dozens of Soviet-style apartments which made the town look quite similar to cities on the Russian mainland, save for the snow-covered mountains directly behind them. This was done on purpose, to make the workers feel at home in the inhospitable environment.18) The Russian settlements even had schools and daycares, and the miners’ families were able to join them on the archipelago. Hein Bjerck, an archeologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, said “Pyramiden was a very, very good place to be, compared to the mainland,” in an interview in May 2018.19)

The 1990s on Svalbard

But the prosperity could not last. Every year, the Soviet mines on Svalbard ran a deficit, and Trust Arktikugol lost money.20) The coal was poor quality, and it was not profitable. When the Soviet crash came, the company could not afford to sustain both settlements. Workers were laid off. The schools were closed, and the children sent home. Eventually, Pyramiden was abandoned entirely. According to Bjerck, “The Russian government wanted to keep a presence there, but they didn’t have any money. The coal company tried to make ends meet.”21)

The 1990s are remembered as a terrible time for the Russians on Svalbard. After the miners’ families were sent home in 1994, the mood in both settlements became increasingly grim. A continuous string of accidents at several of the Russian mines killed over 20 workers in eight years. The accidents were blamed on bad equipment and sloppiness.22) On August 29, 1996, a plane carrying 141 people, all Arktikugol employees, crashed into the Adventdalen valley near Longyearbyen, killing everyone on board23) The toll was equivalent to nearly ten percent of Pyramiden’s population at the time.24) “There was no end to the misery (in Pyramiden) in the 1990s,” said Norwegian journalist Per Arne Totland in an interview in June 2018. In 1998, the decision was made to abandon Pyramiden, and the last coal was extracted from the mine on March 31. By the fall of that year, the town had been forsaken.25)

There are several reasons for why Pyramiden, and not Barentsburg, was chosen to be abandoned. Although Pyramiden was a newer and better maintained city, the coal there was almost entirely depleted, and Trust Arktikugol would have had to dig deeper to access another deposit – an expensive and impractical endeavour.26)

Furthermore, Pyramiden is nestled deep within the Billefjord, which is frozen for almost half the year, and more than 100 kilometers away from open ocean, making it difficult to access via boat, whereas Barentsburg has a warm water port that is accessible year-round.27) Finally, Barentsburg was considered the capital of the Russians on Svalbard, and has a Russian consulate and a helipad, making it a more convenient site to visit politically, logistically, and geographically.28) These reasons made it clear that the Russians could reduce their presence on Svalbard without leaving the archipelago entirely.

It is interesting that the Russian settlements on Svalbard, while being far removed from the mainland, and privy to a unique international convention, have faced many of the same problems as industrial cities on the mainland, including deindustrialization, depopulation, difficulties maintaining infrastructure, and some effects of climate change, such as melting permafrost and rapid warming.29) That being said, the settlements are difficult to discuss in the context of monocities, given that they eventually became economically redundant and were maintained for political ends.30) In this sense, the Russian settlements on Svalbard are sui generis, yet struggle with the most common issues plaguing monocities.

Today, Russia’s presence on Svalbard is discussed in similarly heroic terms as it was in the 1930s. Alexander Veselov, the director of Trust Arktikugol (which continues to operate on the archipelago, and is still owned by the state), said in a March 2019 interview that Pyramiden must be preserved because it is “a historical monument to the Soviet Union’s conquest of the Arctic,” and to “Soviet history.” A special Svalbard Committee has been established, headed by Putin’s closest allies, indicating the government’s renewed interest in the area, and plans are underway to expand the economy in the Russian settlements, by bringing tourists and researchers there.31)

The Arctic is important both economically and symbolically for the Russians, and while Russia has no legal status on Svalbard, aside from its resource-extractive activities, it is keen to remain there, to “have a foothold, and save it for a rainy day,” as Oyvind Nordsletten, the former Norwegian ambassador to Ukraine and Russia said in a 2018 interview. In an age where the Arctic is becoming increasingly ice-free and accessible, having access to territory is seen as a huge benefit, which is why the Russians are reluctant to give up their small but symbolic claim to the islands.

New millennium, new opportunities

Pyramiden stood empty for a decade, until 2008, when joint plans were made between Trust Arktikugol and the Governor of Svalbard to restore the town and market it as a place to see the Soviet Union frozen in time for tourists.32) Soviet imagery appears to sell, as both Russian settlements have started to receive thousands of tourists each year, and the numbers are only growing. In 2014, Barentsburg welcomed 13,000 tourists, and Pyramiden received about 7,000, an increase of 1,000 and 2,000 respectively from the year before.33)

Many Western tourists come to the Russian settlements on Svalbard, especially Norwegians partaking in tourism on the archipelago.34) Svalbard is perhaps one of the most accessible parts of the High Arctic, as it is relatively cheap and easy to reach from both Oslo and Helsinki, unlike parts of the Canadian, Greenlandic, and Russian Arctic.35) The Soviet legacy on Svalbard is difficult to miss, given the presence of two massive Lenin statues in central points of both settlements, which boast being the northernmost in the world.

The Russians appear interested in following the example of Norway, which in the 1990s turned some of its industrial mining settlements into thriving research bases and tourist locales, like Ny Alesund and Longyearbyen, respectively.36) This idea can be confirmed by simple observation – a flight to Svalbard in summer 2018 was full of tourists excited to see wildlife, ski on the rugged terrain, and visit Pyramiden, as well as some biology and engineering students heading to Ny Alesund for several weeks of training. A bus ride back to the airport was full of teenagers from Longyearbyen’s University Research Centre, a research building where students can study geology, geophysics, and multiple other scientific disciplines.

Although they are trailing the Norwegian example by several decades, the Russian efforts appear to be paying off. Pyramiden’s hotel is frequently overbooked, and guests sometimes opt to sleep on the floor just to stay there.37) Cruise ships have also started visiting both Barentsburg and Pyramiden, bringing thousands of guests to the towns. In 2018, over 40,000 visitors to both settlements brought more profit to the Russians than coal mining, said Veselov.

In recent decades, Norway has started introducing greater environmental regulations and put more than half of the archipelago’s territory under environmental protection, a move that was highly unpopular with the Russians, who interpreted the legislation as a covert attempt to push them out of the region.38) Around the same time, the global reliance on coal increasingly diminished, causing the mines to run further deficits. This has continued to push both countries to reevaluate their economic activities on Svalbard.

Nonetheless, both country’s interests on the archipelago appear to be motivated by insecurity, and the fear that if one party leaves, they will lose a valuable foothold in a region that may become pertinent in the future. These issues once again point to the precarious arrangement of the Svalbard Treaty, and relations between the Russians and Norwegians on Svalbard. Nearly 100 years since the Treaty’s implementation, the situation on Svalbard is characterized by a time of change and insecurity, mirroring Russia’s Arctic affairs, and the Arctic as a whole. It remains to be seen what will happen to this unique and remarkable arrangement, and how it will change and affect foreign affairs in the region going forward.

Archival photographs were used with the permission of the Svalbard Museum.

References