Arctic future: Sustainable colonialism?

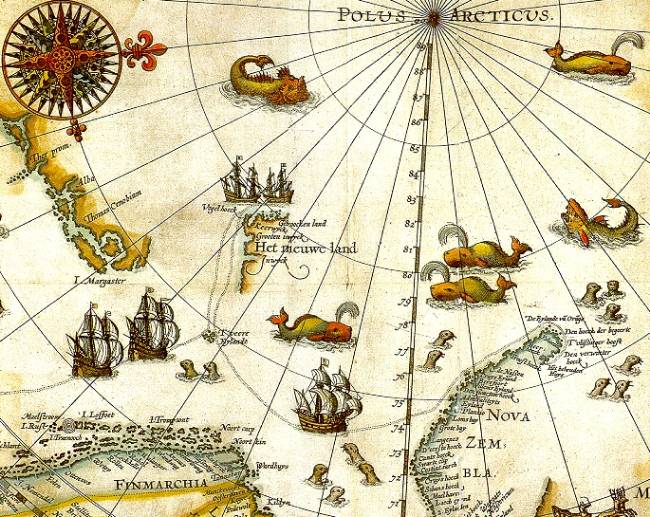

Section from the famous 1599 polar chart showing “the New Land” (Spitzbergen). Map: University Library of Tromsø

In January 2015, the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources study identified that Arctic hydrocarbon resources must remain untouched if the 2°C goal set by the global community is to be met.1) The fact that oil and gas can be produced with greater ease and at less expense in many other parts of the world, coupled with the growing viability of alternative energy sources in the global energy mix and the global drop in oil prices, further undermined the interest in Arctic energy development. Yet, the plans for Arctic energy have not been completely abandoned.2) What drives the current conversations on Arctic energy futures? Is it possible to pursue sustainable development underpinned by the logic of expansive commercial resource exploitation?

The story of two Arctics

The persistent interest in Arctic mineral wealth marks a contradictory relationship between energy and environmental discourses. Repeated discussions held at key Arctic events, such as the annual Arctic Frontiers and Arctic Circles Fora, portray the Arctic simultaneously as a viable future source of valuable mineral supplies and as a fragile space to be protected and preserved. The first narrative highlights the role of capital and technology as a way to ensure a balance between socioeconomic and environmental aspects of Arctic development. The second narrative emphasizes that given the best available knowledge on the dynamics of climate change, global energy transition is incompatible with hydrocarbon development in the Arctic. The first narrative stems from the logic of resource colonialism, the second has its origins in environmentalist discourse.3) The policy options they entail are different.

Arctic “empty, but full”

Natural resource endowment has contributed to constructing the Arctic region as a resource base. Resource colonialism, understood as economically driven discourses, programs, and policies promoting extractive activity on the periphery backed up by administrative, political and/or financial centers,4) discursively turns the Arctic into a space “empty, but full”.5) Scarcity of local population has resulted in an image of the Arctic as a terra nullius, a people-less space that can be explored and conquered. Over the past four centuries, populations of marine mammals, deposits of coal, minerals, oil, and gas have been interpreted by explorers as “Arctic riches” and exported as valuable commodities to distant consumer markets. From whale oil to offshore drilling, the patterns of material production in the Arctic corresponded to international energy flows, embedding the history of Arctic exploration within the context of human’s ever growing energy needs.

The forces driving the incorporation of the Arctic into the global energy landscape came from outside the region. In the eighteenth century, Europeans hunted Arctic whales, walruses and seals for their fur, blubber, skin, and meat so extensively, that “from 1669 to 1800, 86,644 whales were killed by English, Dutch, and German whalers in the seas around Jan Mayen and Spitsbergen”, bringing the population of bowhead whales in the North Atlantic to the verge of extinction within two centuries.6) Now in the twenty-first century, Russia has been pushing forward risky Arctic oil and gas drilling projects to boost its falling production.7) Over the centuries, Arctic colonialism has changed its shape, but it still strongly influences the design of Arctic policies, as well as sustains the asymmetrical power relations between the Arctic as an extractive frontier and the centers of consumption located thousands miles away.

Fragile Arctic

Environmental discourses on the Arctic highlight both local and global implications of Arctic climate change – based on decades of scientific research. And this is what scientists predict: At the local level, extreme weather events, storms, strong winds, are likely to increase.8) The changing weather patterns will most likely constitute serious obstacles to economic activity in the Arctic, as well as negatively affect indigenous communities.9) Since traditional lifestyles pursued by many Arctic indigenous peoples depends on reindeer herding, tensions are likely to arise when pasture areas will shrink due to soil degradation. The movement of sea ice will be less predictable making maritime navigation more hazardous.10) Increase in precipitation combined with warming will lead to desertification, add freshwater to the ocean, and potentially affect ocean currents in the North Atlantic.11) Coastal infrastructure will be challenged by increasing storms and rising sea levels. Thawing ground will disrupt transportation and infrastructure by damaging railway lines, airport runways, oil and gas pipelines, as well as buildings.

In the interdependent global climate system, Arctic changes are likely to have detrimental effects upon the rest of the world. Methane release from the Arctic Ocean and tundra could turn into one of the largest contributors of GHG at a global scale.12) This means that steadily increasing deglaciation will lead to an even greater increase in global temperature, as atmospheric methane release from seas and soils in the Arctic grows due to ice melting and permafrost thawing. The Earth’s surface will be warming more and more as Arctic snow and ice melt, since the amount of the sun’s energy reflected back to space will decrease. The melting of glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet is predicted to contribute significantly (up to 90 cm) to global sea level rise until the end of the 21st century.13)

Climate change will also affect biodiversity, which is important to the functioning of the global climate system, as habitats will be shrinking for polar bears, seals, walrus, and other ice-dependent animals. Shrinking habitats will also put at risk migratory species, such as birds and fish.14) Due to all these reasons environmentalists are utterly concerned about the state of the Arctic, campaigning for turning the waters around the North Pole into a protected sanctuary.15) Through a series of public campaigns, including the ‘Arctic Sunrise’ protest action organized by Greenpeace in 2013 against Arctic drilling at the Prirazlomnaya platform in the Kara Sea, activists attempt to draw media attention to the controversies related to Arctic hydrocarbon exploration, and to present the consumers of fossil fuels with an understanding of the social and environmental impacts of Arctic energy utilization.

Where the two Arctics meet

Over the past 30 years, the September ice cover has declined by more than 30 percent. Satellite data shows that snow cover over land in the Arctic has decreased, and glaciers above the Arctic Circle are retreating. Thawing permafrost, receding ice caps and glaciers, as well as melting sea ice constitute a global threat. Yet, the threat has been turned into a bold promise: earlier unavailable deposits of oil and gas located in the Arctic shelf can soon become accessible for commercial exploitation. Energy companies backed by the official rhetoric of the Arctic states largely adopted the “bringing civilization” approach that maintains energy development and associated infrastructure as a proxy for increasing social well-being in remote communities. Thereby, resource colonialism manifests not only through extending extractive frontiers, but also through interpreting industrialization as a form of development that benefits the extractive communities by resolving economic underdevelopment.

Placed at the heart of climate debates, the Arctic has little to offer to the global energy transition apart from “remaining untouched.” With the increasing salience of climate issues in global energy governance, Arctic hydrocarbons cannot be considered solely as a source of useful carbon energy, but must be seen also as a source of carbon pollution. Disconnecting the Arctic from global energy flows, however, goes against the dominant colonial logic that promoted Arctic exploration for the past four centuries. Turning the Arctic into a global sanctuary is also not a flawless plan, as it ignores the fact that the Arctic is home to four million people who want to preserve their traditional lifestyle while enjoying the latest advances of technology.

The tension between the two narratives highlights that it is impossible to pursue sustainable development underpinned by the logic of expansive commercial resource exploitation. The IMO’s Polar Code, much criticized both by environmentalists and developmentalists, is a good example of a partial policy intervention that results from an attempt to reconcile the two narratives. Designed to satisfy the conditions of both “environmentalism” and “colonialism,” it failed to re-frame the energy-climate nexus in a way that would genuinely reconsider the available policy options. A meaningful entry point needs to be found to disconnect the Arctic from the legacies of colonialism and resolve the contradictions between resource extraction and sustainability.

Concluding remarks

There is a need for a new narrative of the Arctic – not a global resource base, neither a global sanctuary. This new image shall be compatible with the ideas of Arctic people, rather than with discourses from outside the region. One way of re-thinking the Arctic could be through local energy transition. Energy supply from renewable sources in remote off-the-grid areas can increase the resilience of Arctic communities, but also prevent path dependency associated with technological lock-ins created by large infrastructure.16) Self-sufficiency through renewable energy supply would offer an important alternative to reliance on energy infrastructures built within large energy development projects. Remote off-the-grid areas could benefit from renewable and hybrid (wind-diesel and solar-diesel) energy systems ifs policy incentives were to be put in place.17) Who will be in charge of pushing the Arctic energy transition remains to be seen.

References