An old problem, a new opportunity: A case for solving the Beaufort Sea boundary dispute

CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent and USGS Healy cooperating on a scientific mission in the North American Arctic. Photo: Petty Officer 3rd Class Michael Anderson/U.S. Coast Guard

An old problem

The US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) opened an old wound earlier this year when they issued a proposal for new exploration leases off the coast of Alaska—including the possibility of opening up areas currently disputed between Canada and the US in the Beaufort Sea.

The response from officials in Yukon, Canada’s northern territory bordering Alaska, was swift in condemning this perceived violation of sovereignty. Yukon Justice Minister Brad Cather tweeted that “this plan is a violation of Canada’s Arctic Sovereignty & territory that rightfully belongs to the Yukon & Canada.” In an interview with Yukon News the following week, Yukon’s Premier, Darrell Pasloski, reiterated the same position: “We believe that these are Canadian waters.”

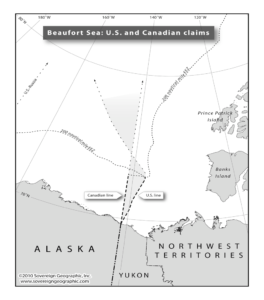

The original source of the dispute can be traced back to the wording of the 1825 Anglo-Russian treaty, written in French, between Russia and Great Britain. These treaty rights were later inherited by the US in 1867, and Canada in 1880, from Russia and Great Britain respectively. Canada claims that the treaty delineates the boundary at the meridian line of the 141st degree on both land and sea; whereas the US claims that it is simply a land boundary and that normal maritime boundary delimitation applies beyond the coast. These different positions only came to a head in 1976, when the US took issue with the boundary line that Canada was using in issuing oil and gas concessions in the Beaufort Sea.

There is a curious twist to this case, however. As Michael Byers, a Canadian maritime law professor, points out in his book International Law and the Arctic, if you adopt the equidistance principle—the legal position favored by the US—it actually ends up benefiting Canada after 200 nautical miles. The opposite is also true, the Canadian position—to follow the 141st meridian line on land and out into the sea—ends up benefitting the US after 200 nautical miles.

While the disputed area has resource potential, the reality is that any deposits, if they are found, are unlikely to be exploited even in the medium- to long-term. Given the technological challenges, the high costs, strict regulations, lack of infrastructure, and implications of the recent Paris Agreement, the deck is stacked against further development in the North American Arctic. This mitigates the political costs of compromise for both sides and paves the way for an agreement.

A new opportunity

Previous attempts at solving this dispute have come up flat. In 2010 then Canadian Foreign Minister Lawrence Canon publicly invited the US government to initiate discussion on solving the dispute. Quiet negotiations began in Ottawa with the blessing of then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, with a follow-up meeting planned in Washington the next year. These talks appear to have stalled, however, after Canon was defeated in the 2011 election and John Baird assumed the role of foreign minister.

With the election of a new government in Canada, Prime Minister Trudeau should invite the US to reopen formal negotiations on the Beaufort Sea boundary. The Prime Minister, having already met President Obama at a widely publicized event to discuss cooperation on environmental issues in the Arctic, should build on this momentum and their seemingly good relationship.

Going forward, it is very unlikely that the US BOEM would issue licenses for the contested area or that companies would be willing to risk investing in the midst of a dispute. Evidence of as much, Secretary of State John Kerry has asked that the State Department be consulted prior to going forward with any sales due to the sensitive nature of the issue. Nevertheless, the renewed focus on the dispute is an opportunity that should not be squandered.

Following the resolution of the Barents Sea dispute between Norway and Russia in 2010, this is a chance for the new Canadian government to resolve one of the few remaining boundary disputes in the Arctic. Not only would this reinforce the image that the Arctic is a region of cooperation dominated by respect for international law, it would be an easy way for Canada’s newly minted Prime Minister to chalk up a victory early in his term, a diplomatic feather in his cap if you will.