The EU’s new Arctic Communication - Part II

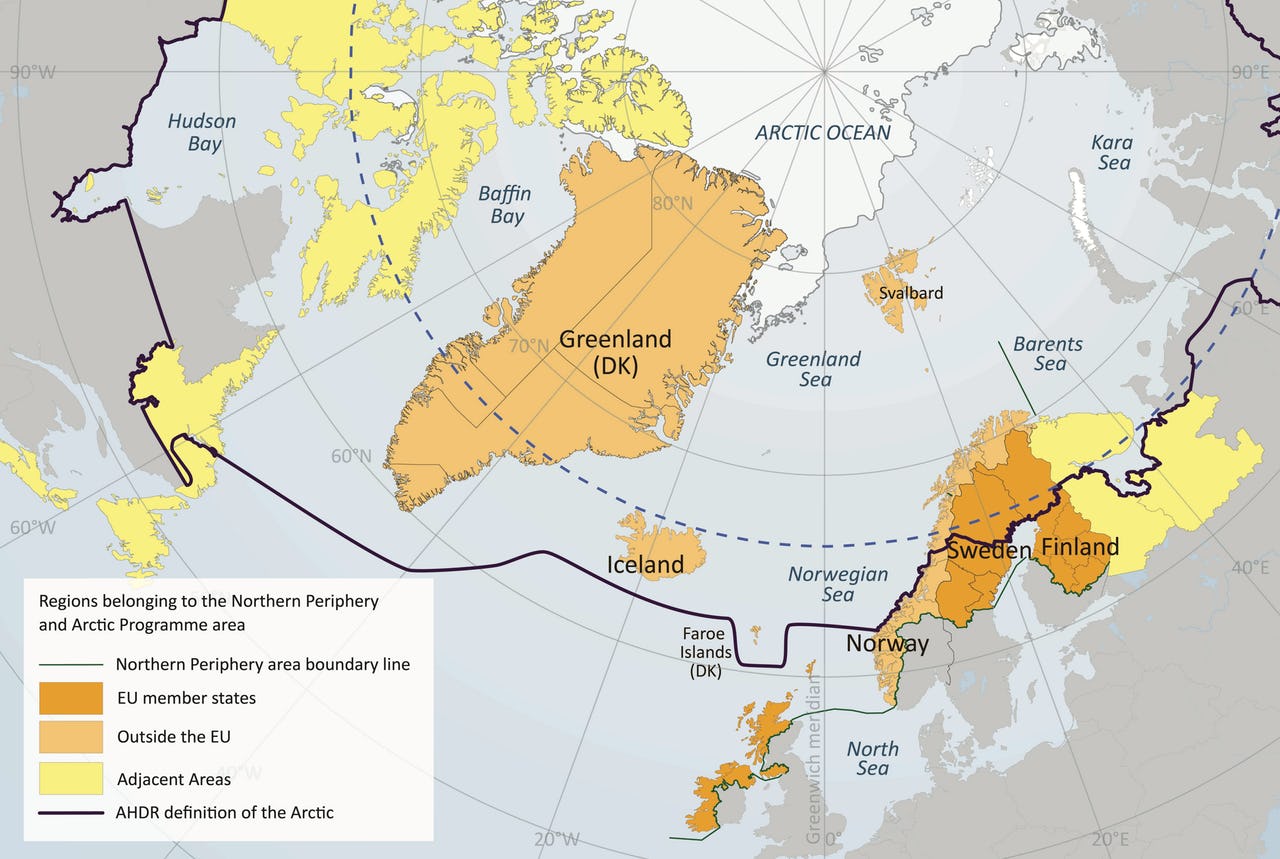

Map of the European Arctic. Map: University of Lapland

Part II: Making a difference: the European Arctic and better coordination

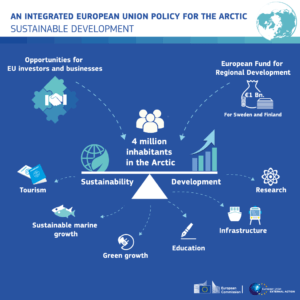

The new EU Communication on Arctic policy includes several aspects that show further change in thinking about the Arctic in the EU’s headquarters in Brussels. While the general statements on climate, Arctic Ocean-related affairs and international cooperation have remained largely unaltered over the years, the increased focus on the European Arctic and finding ways to enhance coordination of Arctic-relevant EU actions are signs of change. First, the European Arctic regions and their development have been finally given a prominent place. Second, as regards economic development, greater attention is paid to a broad range of new sectors and opportunities rather than to overblown expectations of hydrocarbon or minerals extraction or maritime shipping. In the context of the European Arctic, extractive industries practically disappeared from the purview of the new policy statement. Third, the EU proposes some concrete measures to coordinate its Arctic-relevant funding. Enhancing intra-institutional coordination within the Council and the Parliament is also proposed. The Communication reveals future risks related to a possible shift in the EU’s regional funding and to relative silence on environmental questions in discussion on economic development in the European Arctic. Also, concerning the economic development in the European Arctic, the indigenous – that is primarily Sámi – perspective is virtually absent.

The new Joint Communication on “An integrated European Union policy for the Arctic” (JOIN(2016) 21 final) was published on 27 April 2016 and can be found here.

We scrutinize the new Joint Communication in three installments. Part I analyses the very meaning of an “integrated EU Arctic policy,” highlighting limitations and signs of progress. Part II discusses the most visible aspects of this progress: the EU’s approach towards the European Arctic and proposals for better coordination of EU Arctic affairs. Part III will contextualize the Communication in the broader circumpolar setting of Arctic cooperation and the Union’s upcoming Global Strategy.

The different parts of this analysis will simultaneously be published as one policy paper via the ArCticle series of the Arctic Centre (University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland) and can be found here.

More European and more economic development-focused policy

One of the most visible changes in comparison to the 2012 Communication is the place of Europe’s northernmost regions and their closest neighborhood in the reflection on the EU’s role in the Arctic. European Arctic issues have now fully become an integral component of what the EU considers as its Arctic affairs. One of the main points of criticism concerning previous Arctic policy initiatives was the policy’s geographic orientation towards the broader circumpolar North and maritime Arctic. There were calls for a stronger focus on (sub-)Arctic areas that are closer to Europe’s center, 1) including calls coming from the Europe’s northernmost regions. 2) One could argue that it is the European North that could be the EU’s gateway into the Arctic and not the tedious and long-lasting discussions on Arctic Council observer status. 3)

Sustainable development remains the central concept in the EU policy, in line with a maxim that one can make any issue good by putting the word sustainable in front of it. Sustainability is now also fashionably coupled with “resilience”, which appears throughout the document. Referring to “sustainable development” rather than the protection or utilization of the Arctic has also become an imperative when publicly and politically discussing the future of the Arctic region, especially for actors considered external to the region.4) “Sustainable development” circumvents accusations that the EU wants to turn the Arctic into a national park and that its interest is solely in exploiting northern riches. Thus, the new document includes an assurance that sustainable development should be pursued “taking into account both the traditional livelihoods of those living in the region and the impact of economic development on the Arctic’s fragile environment.”

While the Communication’s paragraphs that refer to the Circumpolar Arctic appear to show a stronger environmental focus, those on the European Arctic define “sustainable development in and around the Arctic” primarily as “sustainable economic development” and “sustainable innovation”. There is a new emphasis on the role of non-extractive sectors and new technologies, but growth and investments are the key catchphrases. This mirrors the overall approach of the Juncker Commission, i.e. one focused on jobs, growth and investment.

Innovative Europe’s northernmost regions?

In the 2012 Joint Communication the main concern was “the sustainable use of resources” with other economic activities treated as supplementary. In the 2016 statement, the shift to the European Arctic combined with the less optimistic outlook for large-scale energy, mineral and transport developments leads to a reversal of the earlier focus, with a broader notion of (sustainable) multifaceted economic development moving to central position. Extractive industries are hardly mentioned , and if they are, it is mostly in the context of international cooperation. Instead, much space is given to innovation, prospects of small and medium enterprises, connectivity, bioeconomy, information technologies, renewable energy, and cold-climate technologies. This closely reflects the current discussion on the prospects for regional development in Northern Fennoscandia.5)

The new document looks at the European Arctic in two different ways: from the European perspective and from the Arctic perspective. The former refers to the European northernmost regions, depicting the regions as peripheral and disadvantaged. This perspective could lead to securing much cherished special allocation within structural funding – an allocation the northernmost regions have so far enjoyed due to their permanent structural and climatic handicaps in comparison to other parts of the EU.6) Improving the northernmost regions’ access to the EU’s single market – partly through digital solutions – is another sign of the appreciation for challenges of peripherality. The accessibility of the region could be also improved through hard infrastructure, such as through North-South transport connections. While the latter is merely hinted at in the new Communication, it brings some hope to Finnish dreams of a railway between Southern Lapland and the Arctic Ocean. (Hope if you are a municipality official or mining industry representative, fear if you are a Sámi reindeer herder from North-East Finnish Lapland.) It remains to be seen whether funding opportunities are reflected in the upcoming EU sever-year budget perspective, where net contributors to the EU budget – like Sweden – push for cutting the Union’s budget.

However, the perception of the northernmost European regions changes when we look at them from the perspective of the circumpolar Arctic: from this point of view the European Arctic is not peripheral but comparatively rich, well-connected and highly innovative. In this reading, the region could be central to development of (ideally cleaner) technologies, know-how, and environmentally sustainable technological solutions for activities in the Arctic. The Communication embraces these ideas with references to cold-climate solutions, the development of “Arctic standards” for processes and technologies, emphasis on northern SMEs, collaborative economy and circular economy (growth decoupled from extraction of new resources). These are in fact new EU-wide hip policy phrases. Such a new (as seen from Brussels) way of thinking of the developmental potential of European Arctic regions is particularly strongly present also in Finland’s Strategy for the Arctic region.7) and various reports discussing Finnish and Nordic Arctic affairs 8) There, Arctic and cold-climate solutions are to become one of the drivers for regional and national growth. This emerging coherence of EU, national and local priorities is certainly a welcome development.

A major change in general EU policies – of great importance for the European Arctic – is the expected shift from structural funding towards investment financing. The new document points to the European Investment Bank (EIB) as a source for funding for Fennoscandian cross-border projects.

If after 2020 the EU financial support shifts further towards investment financing (and it currently appears rather likely), one possibility to consider for the EU could be to secure dedicated loan facilities for European Arctic projects, as they may often lose the competition for such resources to Europe’s economic and technology powerhouses, located to the south. A good example is the Nordic Investment Bank, which has recently established an Arctic Financing Facility, putting aside EUR 500 million exclusively for “high north projects”. A similar small targeted programme within the EIB could be at least considered, but the Communication makes no such proposal. Instead, every time the support of the EU investment mechanisms is mentioned in the Communication, the ominous phrase “could help” appears, this telling European Arctic actors: “there are pan-European loans and funds available, so try to fund your needs from these sources”.

While it is appreciable that the Commission tries to find ways for making northernmost regions more economically viable and less reliant on extractive industries and support from the south, perhaps it is high time to openly acknowledge that the character of northern, sparsely populated regions requires a certain ongoing degree of support from Brussels and national capitals in terms of infrastructure, service-provision, and the maintenance of living standards in the North. That does not mean that these regions cannot be innovative and produce added value for the rest of Europe and the Circumpolar Arctic. However, national and European expectations that remote parts of the continent become self-reliant and economically resilient – which stems from the language of the Joint Communication – may push regional and local policy-makers in the North to ultimately rely on extractive industries and sacrificing environmental concerns, in contradiction to EU policy priorities.

Enhancing coordination and engagement?

The most concrete output of the new Communication are new frameworks for better coordination of the EU’s Arctic activities. Creating such venues for coordination was called for by some European Arctic stakeholders, as well as the authors of this piece.9)

First, a temporary forum – called misleadingly “European Arctic stakeholder forum” – for “enhancing collaboration between different EU funding programmes” is to be established. It could be considered a direct result of the Council’s 2014 conclusions and the 2014-2015 consultations on streamlining EU Arctic funding.

Composed of national (open also to Greenland, Iceland and Norway), regional and local authorities, the new forum will attempt to define “key investment and research priorities” for EU funds by the end of 2017. The forum will be complemented by a network of managing authorities and stakeholders from various EU programmes. It is unclear how these processes are to relate to the EU-Polarnet project, which works on European Polar research priorities, also through a broad stakeholder engagement. A certain degree of overlap regarding the research dimension seems unavoidable. Moreover, participation of indigenous peoples and their organizations – chiefly the Sámi and the Greenlandic Inuit – in the new forums is not mentioned. This is disturbing as the communication brings up the question of North-South transport infrastructure or renewable energy projects, and not all of the projects currently considered are seen favourably by indigenous representatives .

It is somewhat disappointing that funding fora are to be temporary in nature, but in the current state of a semi-permanent crisis in the EU, it is a miracle that they are at all considered. After 2017, the envisaged annual Arctic stakeholder conference – perhaps similar to those taking place in macro-regions like the Baltic or the Atlantic – may serve as the continuation of the European Arctic Stakeholder Forum’s work.

Bringing different EU programmes together is something that has been proposed by various actors and analysts for some years. In light of limited EU resources that currently mainly facilitate networking or support smaller projects, exploring possibilities for pulling together resources into joint calls is indeed one of the possible outputs of the proposed coordination fora. In light of the envisaged emphasis on investment financing, the role of the EIB in these coordination frameworks may be of key importance.

Second, while not mentioned in the Communication, the Commission has started to look for a partner to implement something dubbed “EU Arctic Policy Dialogue and Outreach”. It includes organizing several major events with Arctic stakeholders in Brussels and the North. How such a process would look like specifically, what sort of stakeholders it would involve and what impact it could have on the development of the EU Arctic policy is so far unknown.

Third, the Communication concludes with proposals for establishing a Working Party on Arctic Matters and Northern Cooperation in the Council and a similar delegation in the European Parliament. In the diverse EU-Arctic nexus and in light of the complexity of the EU itself, more long-lasting platforms for exchanging ideas and information are welcome. However, the marginal character of Arctic policy in the EU suggests that these coordination venues – if ever established – are unlikely to host particularly energetic debates.

One disappointing feature is the EU policymakers’ weak engagement with indigenous peoples and local Arctic inhabitants regarding EU Arctic-relevant activities. The text of the Communication pushes indigenous peoples’ issues into the “dialogue” corner, rather than raising up their specific concerns throughout the various policy fields discussed in the document. That is not uncommon as indigenous affairs are often constrained in policy debates and documents to what is considered local and traditional, thereby limiting indigenous influence on major political decisionmaking. Ideally, the overarching EU Arctic policy-making could have as one of its key contributions creating spaces for engaging Arctic actors who are likely to be marginalized in broader EU decision-making processes. In particular, the role of the only Arctic indigenous people inhabiting EU territory, the Sámi is not highlighted at all, and it would be fairly natural to consider indigenous perspectives when discussing innovation, SMEs, renewables or bioeconomy. For instance, young indigenous entrepreneurs and nature-based industries are seen as key vehicles for viable indigenous communities.

In a more circumpolar context, annual Arctic Dialogue meetings are mentioned and they have been appreciated by Arctic indigenous organizations, but concrete outputs of this format have been so far hardly visible. Furthermore, the EU is traditionally rather silent on engagement with other Arctic inhabitants than indigenous peoples. Perhaps the EU Arctic Policy Dialogue and Outreach process could fill this gap.

Summary

In sum, we can see the evolution of the EU’s Arctic policy towards a greater focus on the challenges specific to the European Arctic. There are also some concrete proposals for a better coordination of EU Arctic-relevant funding and inter-sectoral communication within EU institutions (the Council and Parliament). But the Communication reveals also potentially problematic aspects of the EU’s future engagement in the North. First, environmental issues are hidden behind sustainability and innovation language, which obscures real dilemmas and value choices that need to be made in Europe’s northern localities that experience structural and demographic challenges. Many actors in the region still hope for (and many fear) possible expansion of extractive sectors in the future. The Communication’s silence on hydrocarbons and minerals will not make these dilemmas go away. Also, innovation cannot be presented as an easy answer to every challenge, value conflict or contradiction. Second, the focus on investment financing can lead to limiting direct programme support for structurally disadvantaged regions in the future. The first problematic aspect will remain with us for decades to come, the second is likely to become a battleground in the coming years, both in Brussels and in the North.

References