Navigating Uncertainties: Finland’s Evolving Arctic Policy and the Role of a Regionally Adaptive EU Arctic Policy

Punkaharju ridge in Finland. Photo: reijotelaranta

The Arctic Institute EU-Arctic Series 2023

- The Arctic Institute’s 2023 Series on the European Union’s Arctic Policy – From a Stakeholder Perspective

- The European Union and its Member States in the Arctic: Official Complementarity but Underlying Rivalry?

- The Crossroads of Science Diplomacy: Italy and the Challenges of the European Union’s Greener Engagement in the Arctic

- Navigating Uncertainties: Finland’s Evolving Arctic Policy and the Role of a Regionally Adaptive EU Arctic Policy

- Mapping Estonia’s Arctic Vision: Call for an Influential European Union in Securing the Arctic

- A Path to Dialogue: The Arctic for EU-Russia Relations

- The Sámi Limbo: Outlining nearly Thirty Years of EU-Sápmi Relations

- How to streamline Sámi rights into Policy-Making in the European Union?

- Why should the European Union focus on co-producing knowledge for its Arctic policy?

- Time for Systems Thinking in the Arctic? The Need for Aligning Energy, Environmental and Arctic Policies in the European Union

- The Arctic Institute’s 2023 Series on the European Union’s Arctic Policy – Final Remarks

Since Russia’s tanks rolled into Ukraine in what Moscow calls its ‘Special Military Operation’ in February 2022, Arctic cooperation has not remained the same. All Arctic states have been affected, but Finland, which has the longest land border with Russia, has had to reconsider its internal and external policies to a greater extent towards Russia. Finland’s geographical proximity to Russia has long forced a balancing act between risks and opportunities. The goal of this article is to trace the evolution of Finland as an Arctic state through its Arctic strategies and re-evaluate both the European Union’s Arctic Policy update of 2021 and Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy 2021, considering the situation of today. This study calls for a more specific and articulated approach from the EU towards the Finnish Arctic, considering its neighbouring location with Russia, climate, security, rights of Indigenous Peoples, trade, and scientific cooperation goals. This article underscores the significance of integrating agile responses into the strategic formulations of Arctic processes when addressing external factors. This highlights the importance of flexibility and adaptability in navigating challenges and uncertainties posed by external influences in the Arctic region.

Finland as an Arctic state

Finland, with its territories extending north of the Arctic Circle, is an Arctic state. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland’s strategic realignment with Europe relied heavily on the concept of northerners, which gained even greater significance after Finland’s admission to the EU in 1995. Initiated in 1999 by Finland as an external policy framework of the EU with its own action program, the Northern Dimension underwent a renewal in 2006 and was subsequently transformed into a collaborative policy jointly implemented by the EU, Russia, Norway, and Iceland. The notion of “northernness” has played a pivotal role in shaping Finland’s strategic stance towards Arctic affairs, effectively underscoring its distinctive position as a nation located in the North. This concept has provided Finland with a framework through which it has approached various aspects of Arctic engagement encompassing political dialogue and practical cooperation. Moreover, the emergence of the concept of “arcticness” in the contemporary era has served to augment Finland’s involvement in discussions pertaining to the Arctic region. By embracing both “northernness” and “arcticness” as integral components of its Arctic identity, Finland has cultivated a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted dynamics inherent to the Arctic.1)

From the early 2000s, in constructing its Arctic identity, Finland started to position itself in its entirety (including Helsinki metropolitan region) as an Arctic state.2) The research findings highlight Finland’s aim to attain broad recognition of its identity as an entirely Arctic state. This objective stems from Finland’s aspiration to establish a strong position in a region that is becoming increasingly important in terms of politics and geography. Different stakeholders in Finland agree on the value of emphasizing Finland’s Arctic identity in its foreign policy.3) Positioning itself strategically, Finland’s Arctic policies leverage its expertise in cold weather conditions, close proximity to abundant natural resources, potential for emerging Arctic sea routes, advanced ice-breaking technology, and the rich cultural heritage of the Sami Indigenous People. These factors have contributed significantly to Finland’s role in Arctic politics and economic matters.

However, according to Väätänen (2021), the Finnish government has not fully developed its approach to the changing Arctic, and thus, the nature of the Finnish approach to the Arctic is anticipatory.4) Finland’s policies and strategies towards the Arctic have relied heavily on anticipation and hope for future economic opportunities that could change the region’s identity and spatial configuration. Anticipatory state identity is not just a simple anticipation of the future but rather an active process of becoming that involves the (re)orientation of the state towards coming closer to the idealized vision of the state within global interactions. This process includes actively anticipating future scenarios based on past learning and information available in the present, ultimately leading to the acknowledgement of the achieved identity both domestically and internationally.5) In anticipation of the future, Finland is increasingly including Arctic dimensions into its foreign and domestic policies, as it strives to become a key player in the region, offering solutions and facilitating connections.

Finland’s Strategy for the Arctic Region 2013

In 2013, Finland adopted its Strategy for the Arctic Region. In that strategy document, Finland envisioned itself as an active Arctic actor, prioritising the sustainable reconciliation of business opportunities and environmental limitations, and leveraging international cooperation. The strategy underscored Finland’s status as an Arctic nation, capitalising on its exceptional expertise to understand and adapt to the substantial changes occurring in the region, such as the increasing economic activities and intensified geopolitical interests witnessed in the area. The Finnish Arctic policy was based on the principles of sustainable development, respecting the basic conditions of the Arctic environment, and aimed to promote international cooperation to maintain stability in the region.6)

The strategy emphasised the significance of Barents cooperation and Northern Dimension partnerships for the Arctic region, including Russia, with the ultimate aim of intensifying collaboration between Russia and the Nordic countries to ensure stability and prosperity in the northernmost areas of Europe. The strategy entailed fostering ties with Russia in Arctic cooperation, recognizing Russia as the primary market for Finnish Arctic energy expertise, and necessitating close collaboration between Finnish and Russian companies for the export of energy resources. Finland also considered other bilateral Arctic partnerships, as well as multilateral partnerships with Norway and Sweden. The strategy published in 2013 expressed optimism for future cooperation with Russia, citing the potential for visa-free travel between the EU and Russia due to growing economic activity and cross-border traffic in the Arctic.

Cooperation with EU institutions and within EU programmes was seen as a crucial aspect of Finland’s Arctic policy, as the country relied on its structural funds and aid for sparsely populated areas to facilitate regional development in the northern and eastern parts of the country. While focusing on economic and research and development opportunities, the strategy document from 2013 barely mentioned military security issues and stated that “a military conflict in the Arctic is improbable – the Arctic States have declared that any disputes will be settled peacefully and in accordance with international law.”7)

Tensions in Arctic cooperation began to unfold gradually after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. The revision of the Strategy in 2016 aimed to renew the Government’s objectives regarding Arctic development and Finland’s role in the Arctic region and a corresponding Action plan was finalized by March 2017; however, it was not until 2021 that Finland completely updated its Arctic policy.

Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy 2021

With the publication of Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy (2021), its Arctic identity has become even more pronounced.8) The Strategy for Arctic Policy 2021 defined Finland’s key objectives in the Arctic region and outlined the main priorities for achieving them. This policy prioritised promoting the welfare and rights of the Saami people, diversifying the economy, mitigating and adapting to climate change, and developing infrastructure and logistics. Finland used the UN Sustainable Development Goals as a guiding framework in its policy document. Finland also recognized the importance of maintaining stability and peace in the Arctic region and contributed to this goal while continuing to prioritise sustainable development, climate change action, and the welfare of the region’s population. This strategy covers two parliamentary terms, which means that it will extend until 2030.

Compared to the Finnish strategy document from 2013, the strategy from 2021 took a more reserved stance with respect to cooperation with Russia. The 2021 strategy stated that the importance of Russia in the Arctic could not be exaggerated, given its status as the largest Arctic nation and the crucial nature of its operations and presence in the region. Russia has placed a significant emphasis on protecting its economic interests and exerting control over the Northern Sea Route. However, the annexation of Crimea and the 2014-22 separatist conflict in eastern Ukraine have resulted in destabilisation in neighbouring regions and Europe as a whole. Russia considers its security to be reliant on military installations and nuclear weapons situated on the Kola Peninsula along with the freedom to operate and access the ocean for its Northern Fleet. Despite these concerns, Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy acknowledged and valued Russia’s role in Arctic environmental cooperation, particularly in the areas of nuclear safety and emissions reduction.

The military security aspects are more pronounced in the 2021 update. Owing to climate change, resource exploitation, and great political interest, military security of the Arctic has become crucial. and regional development began to be examined in the context of security policy. However, still in 2021 Finland was hopeful to ensure stability in the Arctic, by drawing “attention to the possibility of convening an Arctic Summit, which could on one hand enable lifting the environmental issues on the Arctic Council’s agenda at the highest level and on the other hand create a possible forum for addressing security policy matters, which are outside of the Arctic Council’s mandate.”9)

Finland consistently emphasised the importance of strengthening the Arctic Council and the European Union’s Arctic policy. According to the policy document, Finland saw the EU as an important and constructive Arctic actor with access to financial resources, the ability to set high global standards and to mobilize a wide range of expertise. As a member of the Arctic Council, Finland sought to uphold its leadership position in the Arctic and promote a more cohesive Arctic policy involving adequate resource allocation by EU institutions for effective coordination and implementation. Furthermore, Finland aimed to ensure that Arctic cooperation and the unique characteristics of the Arctic region were duly considered in EU funding programmes.

The EU Arctic Policy

The European Union’s Arctic policy has undergone significant evolution since 2008, with the EU continuously refining its Arctic priorities in 2012, 2016 and 2021. Despite the deep historical, geographical, economic, and scientific connections between the European Union and the Arctic region, the EU’s policy text regarding the Arctic does not directly mention the unique conditions of its Member States, namely Denmark (Greenland), Finland, and Sweden. Initially, the EU focused on the security implications of climate change and how it could act as a responsible actor in gaining legitimacy and influence in the region.10) Later the EU shifted its attention to its rights and obligations in the Arctic, with a strong emphasis on becoming a reliable and natural partner in the region.11)

The 2021 update of the EU Arctic Policy brings attention to military security, distinguishing it from its predecessors in 2008, 2012 and 2016, when no mention of the military was made. According to the 2021 policy document, the Arctic has seen a rise in military activity, which has garnered attention along with growing interest in its resources and transport routes. The 2021 update of the EU Arctic Policy highlights the Russian Arctic military build-up as reflective of both global positioning and domestic priorities, posing potential implications for climate change and security challenges. As stated in the document, the EU’s comprehensive observation of Arctic security encompasses its environmental, economic, and political-military dimensions. Moreover, the EU Satellite Centre (SatCen) plays a significant role in providing secured geospatial analysis, enhancing stability, and facilitating preventive measures in response to the growing economic and military activities in the region.

The revised policy addressed the changing geopolitics due to climate change and resource demands. It prioritized international cooperation, countered militarization concerns, and aligned with the European Green Deal to tackle climate change and environmental matters.12) The recent EU Arctic policy outlined engagement with stakeholders through mechanisms like the Arctic Stakeholders’ Forum and Indigenous Peoples’ Dialogue, facilitating ongoing interaction with various groups including the Arctic Economic Council, Arctic Mayors’ Forum, Northern Sparsely Populated Areas network, and the Sámi Council.13) The EU Interreg programmes funding extended the reach of EU actions by involving the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Norway and Russia. The EU demonstrated its commitment to the Arctic through visible actions, such as funding programs, research and innovation initiatives, stakeholder consultation dialogues, and acknowledging the crucial role of Indigenous Peoples. These programmes were key instruments for the EU to steer developments taking place in the Arctic. However, in March 2022, both the Commission and Finland suspended cooperation with Russian entities in research, science, and innovation.

Evaluation of the Finnish strategic landscape post 2022

The conditions for Arctic cooperation have changed dramatically since February, 2022. The risks associated with Russia began to materialise in both foreign and domestic policies in Finland, as evidenced by decisions such as joining NATO, curtailment of economic cooperation, and decline in trade with Russia. In a move signifying the end of the era of military non-alliance, Finland filed for NATO membership. The Finnish parliament demonstrated strong support for this decision, voting 188-8 in favour of Finland’s membership in the defence alliance.14) As of 1 April, all NATO member states ratified Finland’s accession protocol, and Finland became an official member on 4 April 2023. As a result of Finland joining NATO, the alliance has a lengthy land border with Russia.

In the summer of 2022, Finland announced plans to construct a 200 km eastern border barrier fence along Finland’s long border with Russia to prevent large-scale instrumentalized migration and improve the effectiveness of territorial surveillance. Currently, the project is underway, and a pilot section is already under construction. The anticipated completion date for the entire fence is set for 2026, and the estimated total cost of the project is around EUR 380 million.15) However, concerns have been raised regarding the potential impact of such barriers and fortified fences on animal migration and the survival of various species, particularly in the context of a changing climate.16)

In May 2022, Finnish partners withdrew their construction permit application for the Hanhikivi 1 nuclear power plant. The project started in 2013, when Fennovoima, which was mostly owned (66%) by Voimaosakeyhtiö SF, a Finnish company with shareholders that included major Finnish corporations and several local energy companies, signed a fixed-price contract with Rosatom Overseas to build a 1200-megawatt electrical (MWe) nuclear plant at Hanhikivi.17)

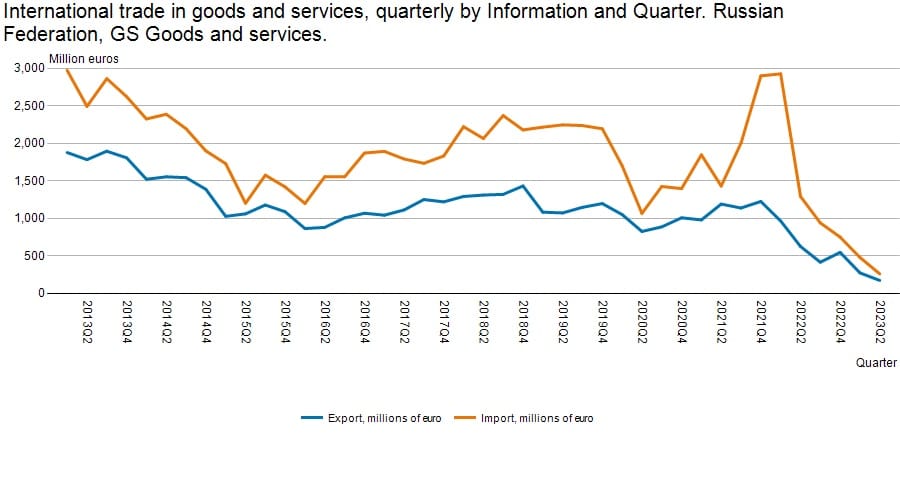

Since February 2022, international trade between Finland and Russia has experienced an unprecedented decline (see Figure 1). Trade between Finland and Russia decreased after 2014 due to sanctions. In late 2021, after the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, there was a brief increase in imports from Russia to Finland. In 2023, Finnish trade with Russia continues to be marked by historically low volumes.

In October 2022, Finnish Government commissioned a report “Arctic cooperation in a new situation: Analysis on the impacts of the Russian war of aggression”, a background study on Arctic policy commissioned by the Prime Minister’s Office for analysis and situational picture of Finland’s Arctic policy.18) The results are used to monitor the objectives of the Arctic Policy Strategy and provide a situational picture of government negotiations. The Arctic situation has undergone significant changes, marked by an increase in geopolitical tensions. As indicated in the report, the prospective NATO membership of Finland and Sweden would introduce new regional tensions, although it was believed that establishing a stronger military balance in the Nordic region could contribute to stabilising the security environment. The impacts on green and just transition in the Arctic following the events of 2022 were found to be intricate, with the EU assuming a critical role in Finland’s Arctic objectives. Additionally, the report underscores the significance of international cooperation and research in the Arctic region, particularly in the realm of sustainability and climate change.

Foresight and targeted approach

Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy 2021 and EU Arctic Policy were released in 2021. Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy 2021, with a timeframe extending to the 2030s, potentially faces challenges from sudden environmental or external changes, as highlighted by the February 2022 events. Finland’s Arctic policy requires a delicate balancing act to address the region’s evolving landscape. While the EU and Finnish Arctic policy documents remain relevant, it is evident that strategic text regarding cooperation with Russia is no longer applicable. Furthermore, the current state of Arctic cooperation has been fragmented and driven by military security concerns. The current geopolitical landscape underscores the validity of an anticipatory approach, reaffirming the pertinence of proactive envisioning and preparing for future scenarios in both Finland’s and the EU’s Arctic policies.

It is crucial for policymakers and stakeholders to adopt a comprehensive and nuanced approach to address the unique challenges and opportunities present in the Arctic region. By considering the specific context and dynamics of each Arctic state, such as Finland’s proximity to Russia, policymakers can develop tailored and effective strategies. This includes considering not only military security concerns, but also a range of factors, such as environmental sustainability, scientific cooperation, and economic development. Setting general priorities is insufficient; instead, specific actions and targeted approaches are necessary to fully grasp and tackle the complexities of the Finnish Arctic. By embracing a future-oriented perspective and implementing focused strategies, both the EU and Finland can effectively navigate the challenges and seize opportunities presented by the Arctic.

The unforeseen challenges faced by Arctic policies during recent events highlight the necessity for enhanced foresight in Arctic policy-making. EU Arctic Policy 2021 acknowledges the need for strategic foresight, including collaboration with partners and NATO, to address the security impact of climate change. By including actionable foresight elements in Arctic policies, stakeholders can quickly respond to unexpected events or changes in the regional environment and adjust their strategies and priorities, as needed. Overall, a more comprehensive approach and wider discussion at the political and civil levels, including citizen-centric participatory approaches, are necessary to effectively address the various challenges and opportunities presented by the Finnish Arctic and ensure that the region remains stable, secure, and sustainable over the long term.

Finland’s Arctic policy in the current situation necessitates a delicate balance encompassing various factors and requirements, achieved through a comprehensive and nuanced approach that considers specific regional dynamics and embraces strategic foresight. In the context of the current pause in Arctic cooperation at the Arctic Council level, the adoption of a foresight approach holds the potential to empower Finland in formulating future action scenarios that would encompass its future relations with neighbouring Russia. Furthermore, by adopting a more elaborate and targeted approach towards Finland and the European Arctic in its Arctic policy, the EU can effectively address the complex challenges posed by the Arctic environment, mitigate potential risks and externalities, and enhance its preparedness for geopolitical developments.

Alexandra Middleton, a researcher with a PhD in Economics and Business Administration from the University of Oulu, Finland, her research focuses on sustainability in the Arctic.

References