The Arctic Other in American Cultural and Intellectual History

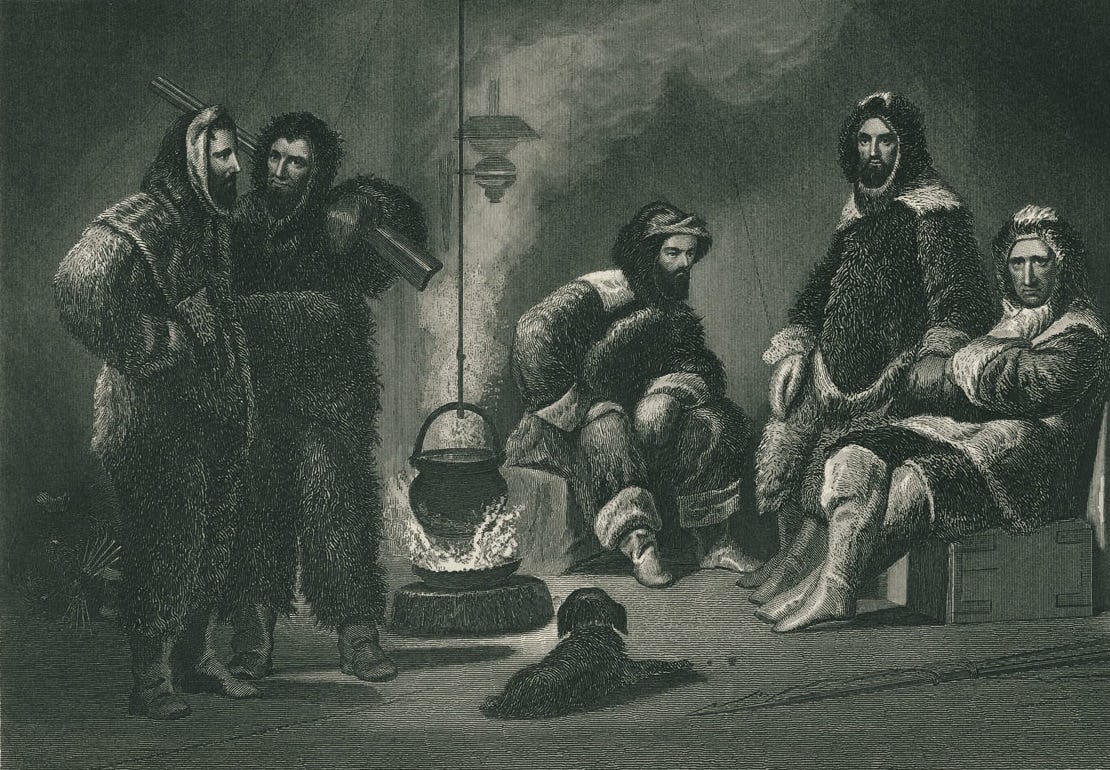

Engraving of Elisha Kent Kane and his crew during their 1853 expedition to recover Sir John Franklin’s lost crew. Photo: Elisha Kent Kane

The ebb and flow of American Arctic anxiety

Though the U.S. has had a robust national conversation about the shifting state of the Arctic in recent years, analysis of the nation’s relationship with the region often lacks a sense of the longer American cultural and intellectual history of the Arctic. In the past decade, U.S. media, various think tanks, and a bevy of new Arctic scholars have contributed to a floodtide of interest about the country’s stakes in the Arctic. It has been urged on by heightened awareness of unprecedented sea ice retreat, the seemingly aggressive aspirations of Russia, and media sensationalism. Anxiety over vast Russian claims to the Arctic have provoked a Cold War vision of a riven international system, but perhaps more so a sense of a potential nineteenth-century imperial-style scramble for resources.1) In its wake lies an assortment of conferences, reports, white papers, and statements by foreign policy and military elites.2) Recent U.S. government policy announcements, however, advocate a safe, sustainable, and prosperous Arctic.3) These largely agreed: the U.S. should project more power into the Arctic, invest in its stability, and accede to the international frameworks that impose order there, rather than engage in a geopolitical contest. Generally, the earlier anxiety about the region has receded, and calls for robust engagement there are unlikely to stir extensive federal action.

If we view these developments through a narrow temporal lens, we can comprehend why the U.S. has largely been seen as a reluctant Arctic actor and assess why the pressure on policy-makers did not lead to the deployment of new icebreakers, accession to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, or greater endorsement of the Arctic Council. The U.S. was mired in recession when the Arctic suddenly appeared ominous a decade ago; the fulcrum of national security policy remained in the Middle East and Southwest Asia, and inaccessible Arctic hydrocarbons appealed far less than the domestic energy boom unleashed by fracking. Anachronistic fear of a new “cold” war -or the spectre of Chinese control of the Arctic – could not overcome this.

Strict political economy and geopolitical analysis leaves much out, however. Viewed through a broader temporal and spatial lens, the recent, brief, and contentious U.S. debate about the Arctic leading up to its chairmanship of the Arctic Council between 2015 and 2017, followed by relative apathy, is familiar. Indeed, it rhymes with the past two centuries of Arctic aspirations, delusions, and withdrawals. This broader context helps to understand the acute policy-making process within a longer cultural and intellectual history of the U.S. and the Arctic. Yet, serious scholarship in this subfield remains scant. Traditionally, Arctic writing has been the redoubt of hagiography for the American men and vessels that have confronted or surmounted the Arctic, which continues to be the case.4) Only recently have studies sought to embed U.S. thought and interaction with the Arctic in a more textured historical context.5)

History does not dictate current U.S. thinking and policy about the Arctic, but it reveals a longer American pattern of marginalizing both the Arctic and its peoples as other. Perhaps more than any other place in the Western Hemisphere, the Arctic has remained persistently outside the realm of U.S. conceptions of national identity, security, and history. At discrete moments, it has provided a stage on which Americans can perform some ideal, extract some victory, distract from some anxiety. But it has always been an other space, exoticized and exploited to different ends, then departed and ignored. Thus its value has resided as much in the cultural and intellectual as in the geopolitical and economic realm. The mid-nineteenth-century American perception of the Arctic – the era when Americans’ notions of it first came into focus – casts light on this longer history.

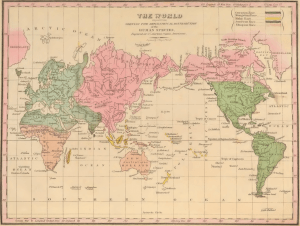

Seeing the hemisphere, placing the Arctic

Amid the nearly all-encompassing vision of the hemisphere that many Americans developed in the nineteenth century, the Arctic remained quietly on the margins. Although the U.S. would purchase the tsar’s mammoth claims to Alaska in 1867, that territory, the Canadian archipelago, and Greenland remained outside Americans’ sprawling plans for conquest, settlement, and economic gain. Until the Civil War (1861-1864), sundry Americans imagined a continental empire even grander than that attained with the conquests of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Students of American history are most familiar with tales of filibusters, rogue U.S. citizens independently laying claim to territory in Central America and the Caribbean. Along the border with Canada, others likewise thought it a matter of time before the U.S. seized its northern neighbor. Within the violent logic of nineteenth-century expansionism – in which private initiative was fused with government backing to engulf inconceivable stretches of territory – such grand plans made sense. With the the retreat of the French in the early nineteenth century, U.S. gains in the War of 1812 with Britain, and the atrophy of the Spanish empire throughout this period, the possibility of an American hemisphere beckoned many.

These claims to vast territories or influence over them were accompanied by a major academic endeavor to examine and classify the hemisphere throughout the 1800s. This played out in several of the disciplines that were being institutionalized by the middle of the century. In this process, American historians, archaeologists, linguists, and ethnographers assembled huge amounts of data in order to tell the history of the hemisphere prior to, during, and since European colonization.6) To this end, individuals and institutions collected American Indian lexicons and oral traditions, skeletons, animal and plant specimens, historical artifacts and documents. Collecting advanced in stride with the country’s expansion. Meanwhile, collections ensconced in the burgeoning historical and scientific societies told a comprehensive story of the hemisphere, which could be used to justify the nation’s expansive aspirations throughout the Americas.

Two examples drawn from this ferment – in the inchoate disciplines of archaeology and craniology – show how the northern and southern continents of the New World appeared linked by a common cultural heritage. However, they meanwhile suggest that the Arctic was separated from this larger hemispheric story. In the first instance, historians and archaeologists examined the earthen and stone architecture of pre-contact American Indians in order to tell the history of “American antiquity,” as they conceived it. They elaborated a theory that an ancient people with a common culture had populated the Americas, migrating southward from Canada, along the Mississippi River, and into Central and South America.7) An array of U.S. and international scholars generated tremendous popular interest in this nearly hemispheric history through the first half of the century, which provided an epic past that Americans could refer to.8) However, while this included British Canada and Latin America within its scope, it noticeably excluded territory and culture in the North American Arctic. The Arctic remained a place without perceivable architecture, revealing that its inhabitants had not truly settled and improved their territory. In a nineteenth-century Euro-American worldview, it followed that indigenous peoples of the Arctic could not count as historical agents. The Arctic and its peoples, in other words, were outside of history.

In a second discipline, in tandem with that inquiry, the new science of race also placed the North American Arctic as a separate space, kindred with Asia rather than with America. Dr. Samuel George Morton, who emerged as the nation’s preeminent craniologist, posited that human history could be read in the cranial variations of the world’s distinct peoples, which he divided into the five major groups below.9)

Morton’s vision of human history defined sub-Arctic North America (all territory south of Greenland’s southern tip at 60 degrees N) and the entirety of South America as the “American Race”. The peoples of the Arctic, however, were severed from this category. Morton had struggled to place “the Polar Family” in his global topology, as they seemed to diverge markedly from more southern indigenous Americans. Instead, the crania of indigenous Arctic peoples – gathered and dispatched by various Arctic exploring expeditions – led him to craft the hybrid category of Mongolian-Americans. This fused the origins of North American Arctic peoples with the populations of the Asian steppes, Siberia, East and Southeast Asia – a region which Americans perceived by mid-century as stagnant and inferior to the progressive history of Europeans and their New World descendents. “The concurrent testimony of all voyagers,” Morton wrote of the Polar Family in particular, “shows these people to be, both in appearance and in manner, among the most repulsive of the human species.”10) In depicting them as such, he wrote their history and identity out of the Americas. In this detachment of the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, and what would become Alaska from the greater vision of the Western Hemisphere, these intellectual currents reflected a broader nineteenth-century U.S. tendency to cast the Arctic and its peoples beyond the nation’s geographic imagination, prospects, and identity.

Kane’s Arctic stage

Such was the image of the American Arctic under construction by the middle of the nineteenth century, separated by these divisions of history, culture, and race. When the rare American crossed those lines and entered the Arctic, he – for Arctic travel was nearly always a masculine undertaking – was entering a different sort of space. This is the context for analyzing how Americans encountered and recounted the people, the environment, and the experiences they had there. Generally, nineteenth-century Americans in this period used the Arctic as a stage to act out some national aspiration or ideal.

Among these Arctic sojourners, Elisha Kent Kane stands out. In 1850, Kane joined the Grinnell Expedition, which sought to recover the long-lost crew of Sir John Franklin’s doomed 1845 attempt at the North West Passage (along the way, he collected crania for Morton’s research). Kane leveraged the dramatic Arctic endeavor toward his own celebrity, and in a vividly publicized reprisal, returned amid extraordinary fanfare to seek Franklin in 1853. Through his skillful use of the public lecture, mass produced newspaper, and enthralling travel writing, Kane became, perhaps, the most famous man of his age.

The manner in which Kane framed and justified his Arctic experience for this mass American audience shows how malleable the features of the Arctic were for him. Kane made the improbable argument that Franklin’s crew had survived for years on the shore of a clement Arctic polynya, or open polar sea. In recent years, that Renaissance belief had been revivified by modern science; Kane then refracted it through the mania of mass culture.11) Esteemed oceanographer Matthew Fontaine Maury, head of the Naval Observatory and Hydrographic Office, had offered a sober and speculative vision of a polar sea: Based on the migratory patterns of whales and the necessity that the warm Gulf Stream empty somewhere, it appeared that hospitable polar waters should exist for at least for some portion of the year. But in Kane’s depiction, speculation became certainty, a sometimes open sea widened, warmed, and filled with fauna, and the hope that Franklin’s crew survived on its shores brightened. Well-documented Arctic geography and the likely fate of the sailors became irrelevant.

Instead, the Arctic became a stage for Kane to perform a particular model of the American man, far from an urbanizing, industrialized nation on the brink of a sectional war over the nation’s soul. In public anticipation of his 1855 return and then in the immensely popular account of the expedition that he swiftly published, Kane emerged as the paragon of mid-century manhood. In his intrepid attempt to both penetrate the secrets of the Arctic and wrest Franklin’s crew from it, he fused the public ideal of progress, the romantic aesthetic of the poet-traveler, and the domestic virtue of restoring Sir Franklin’s sacred union with his wife (indeed it was Lady Jane Franklin who galvanized much of the transatlantic anxiety about his fate).

Kane’s venture inspired observers throughout the country to envision a nation transcending the sectional conflict over slavery. Arctic expeditions assembled men from throughout the union on a seascape remote from sectional antagonism and free of the divisive enticements of conquest, extraction, and development. For the U.S. as a nation, Kane’s expedition was reminiscent of its seminal Pilgrim settlements in New England, for “…a patriotism as ardent and enthusiastic as a pilgrim’s religion devoted him to his country’s glory.”12) Indeed, Southerners joined Northerners in applauding the undertaking. Henry Clay, formidable Kentucky senator and architect of the Compromise of 1850, was the major crucial voice behind congressional support for the Arctic voyages. U.S. Naval Observatory head Maury, writing in New Orleans’s popular DeBow’s Review, asserted the higher unity organizing these missions: “Men of science, as such, know no internationality. They owe allegiance to but one power, and that is Truth; and they are all fellow-citizens alike of the great Republic of Science.”13) As the sections moved toward war, the Arctic drew American attention to distant shores, allowing some to imagine an identity and order greater than the political structure that would soon collapse.

As the Arctic was used by Americans to escape the reality of their country’s political geography, while there Kane also ventured beyond the rules thought to govern civilized life. While Kane’s 1854 account of his first Arctic expedition, The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin, was a generic adventure travelogue, his second in 1856, Arctic Explorations, hewed markedly toward ethnography. It dwelt at length on the indigenous Greenlanders in particular – their physiognomy, clothing, social norms, diet, economic life, and language. Throughout this account, we see him struggle to comprehend and place the indigenous peoples of the Arctic within his conception of humanity and law. In doing so, Kane echoed the blunt racism of Morton’s earlier appraisal of Esquimaux (the exonym of the day). Morton had concluded that they “are crafty, sensual, ungrateful, obstinate and unfeeling…Their mental faculties, from infancy to old age, present a continued childhood: they reach a certain limit and expand no farther…In gluttony, selfishness and ingratitude, they are perhaps unequaled by any other nation of people…”14) Amid the wretched lexicon of nineteenth-century racism, such language placed the indigenous Arctic peoples significantly lower than the American Indian, who could remain eligible, in theory, for civilization. Kane had imbibed this prejudice and was swift to condemn them along these lines. Recounting their tendency to steal and shirk all responsibility, he often cast them as a burlesque comic relief in his survival story.

Unlike Morton, the armchair traveler, Kane was nonetheless dependent upon them for survival during his two winters in Baffin Bay. To manage this cognitive dissonance of depending on a race he deemed inferior, he cast the indigenous as subordinate partners in a mock diplomacy. To engage his readers, Kane fashioned himself as the architect of an astute Arctic diplomacy, in which his manufactured goods were exchanged for their animal protein. Kane patted himself on the back for instituting civilised diplomacy in such challenging circumstances. In a gust of bravado, Kane explained that this reciprocity was undergirded by the indigenous’ recognition that “the whites are, and of right ought to be, everywhere the dominant tribe.”15) But this tenuous non-aggression pact often broke down, leading to burlesque humor regarding indigenous knavery.

Though Kane pretended that his roving brig could project the law of nations into the Arctic, this diplomacy was a mockery of inter-state relations: based on the threat of violence, maintained by bare necessity, undermined by racism, and easily abandoned. Though he expressed an unprecedented ethnographic interest in Greenland’s indigenous peoples, he consigned them to the far fringe of the human family – stagnant and incapable of progress. As they did not reach the threshold of civilization, their societies could not be incorporated in the community of nations. They were thus excluded from Kane’s vision of progressive history and the geography of international relations. When the terror of a third winter stuck in the ice loomed, Kane and crew turned their back on the Arctic and its people. While he returned to much fanfare, the popular Arctic fascination he had stirred largely receded during and after the Civil War, and would not rise again until the sensationalized attempts to attain the North Pole in the next century. Though Kane’s quest for Franklin excited U.S. audiences, the Arctic and its people would remain estranged from the nation’s cultural, economic, and political reality.

Then and now

Much has changed since the mid-nineteenth century regarding the Arctic imagination and policy of the U.S., as well as its relations with indigenous peoples of the Arctic. At the conclusion of the U.S. chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2017, for instance, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson joined the other seven Arctic countries in “Recognizing the rights of Arctic indigenous peoples and the unique role of the Permanent Participants within the Arctic Council, as well as the commitment to consult and cooperate in good faith with Arctic indigenous peoples and to support their meaningful engagement in Arctic Council activities…” The discourse has clearly changed, and, unsurprisingly, the U.S. has invested far more in Alaska and the broader Arctic more broadly since the time of Kane’s voyage. But in my contribution to a new anthology by an array of academic and policy experts, I explore how, contrary to other Arctic states, the U.S. has not moved far beyond its nineteenth-century estrangement from the Arctic, which it persistently declines to integrate into its geographic imagination, national identity, and policy-making.

Derek Kane O’Leary is a PhD Candidate in University of California, Berkeley’s Department of History. He is an Editor of the Journal of the History of Ideas blog, which always welcomes new submissions from scholars across disciplines. Small portions of the this are drawn from a forthcoming article in MASKS, a journal for practitioners, theorists, and historians of design, entitled “Arctic Polynya”, which explores Americans’ conception of the open polar sea theory in the nineteenth century.

References