From the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress to the Arctic: the Cooperation Triptych

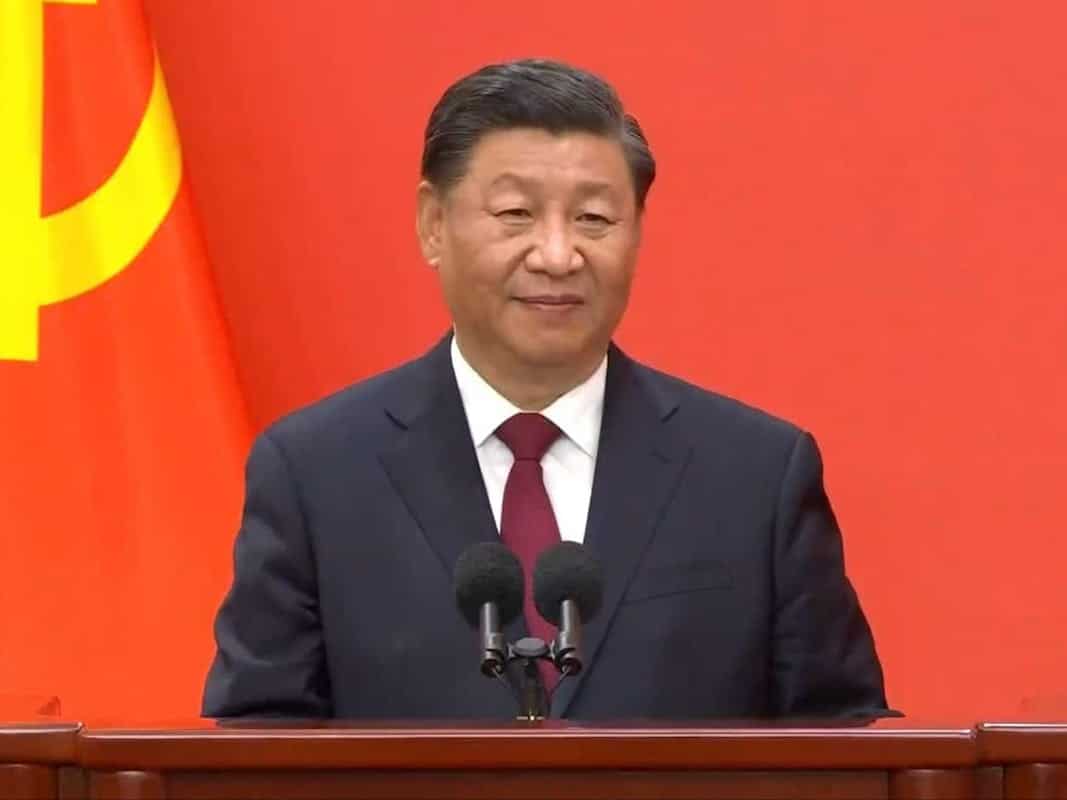

Xi Jinping has recently obtained a historic third mandate as a General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. He has also been confirmed as the chairman of the Central Military Commission. Photo: Wikimedia

The Arctic Institute Arctic Collaboration Series 2023

- Arctic Collaboration: The Arctic Institute’s Spring Series 2023

- Decolonization and Arctic Engagement: A Critical Analysis of Resource Development in the US Arctic

- Where do we go from here? The Fate of Scientific and Cultural Collaborations for Young People in the Arctic

- Conflict or Collaboration? The Role of Non-Arctic States in Arctic Science Diplomacy

- The Like-Minded, The Willing… and The Belgians: Arctic Scientific Cooperation after February 24 2022

- Can Arctic Cooperation be Restored?

- China-Russia Arctic Cooperation in the Context of a Divided Arctic

- From the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress to the Arctic: the Cooperation Triptych

- The EU as an Actor in the Arctic

- Vulnerability in the Arctic in the Context of Climate Change and Uncertainty

- The Ukraine War and Arctic Collaboration: Final Remarks

Last October, the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was held in Beijing. The gathering in the Great Hall of the People symbolizes the Party’s highest political moment and is held every five years. As usual, the CCP’s General Secretary Xi Jinping presented a report summarizing the past five years’ work and drawing general lines for the next five. Analyzing Xi’s Congress report makes it possible to envision the Politburo’s following policies in specific geographical regions and policy areas. This article elaborates on the Congress Report’s relevance for China’s Arctic policy in the new security situation in the Arctic. As a result of this investigation, I identify a cooperation triptych. It consists of three key dimensions: the development and investment in science, the endorsement of the concept of community with a shared future, and multilateral governance. All these three aspects indicate how China’s Arctic engagement will not go through any substantial change. However, it will stick to cooperative measures to not further destabilize Arctic international relations.

Through the Congress Report

On October 16th, Xi Jinping presented the Report to Congress. While the 2017 Report celebrated China’s global rise through soft power, the last one highlights how the changed external environment presents increasing challenges for China,1) ranging from slow down of the global economy to some regional conflicts and disturbances. As Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has shaken major power relations, national security received much more attention. Xi Jinping speaks about holistic national security, emphasizing food, energy, resources, supply chain and technology, and mentions of the word “security” (安全 – anquan) almost doubled compared to the 2017 report.

While the focus on national security influenced by global instability shows new priorities in Xi Jinping’s agenda, for China’s Arctic policy, it might represent a vital element of continuity by further endorsing international cooperation in the region. The typical cold-war concept of security is principally based on prioritizing state-centric military security over environmental degradation. From the early 1990s, environmental security played a pivotal role in Arctic states agendas and encouraged Arctic stakeholders to build common ground. China has gradually improved its Arctic scientific research engagement and technological capabilities through regional governance mechanisms, such as the Arctic Council Working Groups and as a member of the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC).

Science and technology

In the 2022 Congress Report, an entire section is dedicated to science and technology (科技 – keji), which are mentioned more often than in the previous report in 2017.2) Science and technology are addressed as a “primary productive force” for China’s transformation into a “modern socialist country“,3) suggesting that Beijing will improve a self-reliant technological system, lessening dependence on foreign aid and pursuing national economic development.

The Congress Report states that China: “will increase investment in science and technology through diverse channels[…] We will expand science and technology exchanges and cooperation with other countries, cultivate an internationalized environment for research, and create an open and globally-competitive innovation ecosystem.”4) When speaking about the Arctic, science and technology are tightly linked. Particularly, icebreakers enhance the possibilities of conducting Arctic scientific research. China has improved its icebreaker fleet in the last decades, and its third polar icebreaker might be ready for 2025.5) From the perspective of the US, the upgrading of China’s Arctic scientific capabilities is oriented to conduct also intelligence and military applications in the region.6)

Advancements in technology and science in China’s Arctic strategy (published in 2018) are developed through scientific cooperation: “China will improve the capacity and capability in scientific research on the Arctic, pursue a deeper understanding and knowledge of the Arctic science […] supports pragmatic cooperation through platforms such as the International Arctic Science Committee, encourages Chinese scientists to carry out international academic exchanges and cooperation on the Arctic, and encourages Chinese higher learning and research institutions to join the network of the University of the Arctic.”7) Based on this formulation, we can anticipate that China will work on enhancing scientific cooperation opportunities in the Arctic.

China’s capabilities to conduct joint scientific research in the Arctic region are strictly connected to international cooperation and influenced by China’s relations with the Arctic States. It also depends on China’s status as a non-Arctic country with no sovereign rights in the region and solid interests in boosting its influence. As an observer to the Arctic Council, China “has to demonstrate political willingness as well as financial capability to contribute to the work of the Permanent Participants and other Arctic Indigenous peoples.“8)

China has to consider the almost three-year absence of Chinese scientists from main research bases as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the new precarious political situation between the Arctic States due to the war in Ukraine and the skepticism about military-end usage of its polar icebreakers. These factors might induce China to take a step-by-step approach that sticks to the cooperative approach, meaning that it will prioritize its well-established scientific projects and partnerships in Norway and Iceland. Recently, Chinese researchers have told Voice of America (VOA) that there are plans to immediately resume work in two of the most important Chinese outposts in the Arctic: in Svalbard to the Yellow River Station in Ny-Alesund, which is operated by the Polar Research Institute of China (PRIC); and in Iceland to the China Iceland Arctic Research Observatory (CIAO).9)

The work of the Arctic Council has suffered a slowdown. Its probable reshaping may not change the necessity for China, as a non-Arctic country, to respect Arctic states’ sovereignty rights, and show its commitment to the work of the working groups and its financial capability to improve scientific knowledge. Restoring the work at the research bases might help let things work again, and the existing scientific collaboration might provide common ground to enhance cooperation. However, most of the work will undoubtedly depend on the evolution of the war in Ukraine and on the ability to keep the Cold War mentality from regulating international relations in the region.

On its side, China is also intensely interested in not compromising its relations with the Arctic-7. Therefore, engagement in scientific cooperation is also seen as a way to stay caught up in this frozen mode of the Arctic relationship, where China still shows great interest.

Community with a shared future

The concept of a “community of common destiny” was first mentioned by former CCP’s General Secretary Hu Jintao at the 17th National Congress in 2007. Xi Jinping has slightly modified the concept into “a community of shared future.”10) Both concepts are based on the idea of common destiny. What slightly changes is the concept’s dimension and projection at the global level. During Hu’s era, the concept was mainly shaped and endorsed to manage relations with neighboring countries, especially Taiwan. In Xi’s era, the concept has been elevated to a new way of looking at international relations. Its ambitiousness lies in the win-win strategy where all stakeholders benefit from global cooperation, offering an alternative model to the East-West dichotomic perspective. For example, massive projects like the Belt and Road Initiative are deeply rooted in a globalized economy and a willingness to create an economic infrastructure where many stakeholders might share benefits.

The Congress Report discusses this concept in the 14th section: “China is committed to its fundamental national policy of opening to the outside world and pursues a mutually beneficial strategy of opening up. It strives to create new opportunities for the world with its own development and to contribute its share to building an open global economy that delivers greater benefits to all peoples”.11) The endorsement of economic globalization and the creation of shared-benefit platforms in the Arctic means the development of the maritime economy through blue economic corridors. The maritime economy is categorized into three sectors: marine fishery and aquaculture industries; salt industry, offshore oil and gas, mining, and shipbuilding industries; transport industry and coastal tourism.12)

China’s “Vision for Maritime Cooperation on the Construction of the Belt and Road”, jointly released in 2017 by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), suggests the creation of three blue economic corridors, one of each is the Arctic corridor. In their investigation of the role of the blue economy passages, scholars Jiang and Chen (2019) highlight how maritime partnerships are based on the strategy of ocean power (海洋强国 – haiyang qianguo) and the principle of shared future (命运共同体 – mingyun gongtongti).13) While the authors suggest the ASEAN model of regional cooperation for the first two blue economic passages, for the Arctic, they look at medium and long-term strategy mainly based on relations with Russia.

So far, the development of the blue economic corridor in the Arctic has led to improving bilateral relations between Russia and China, mainly through LNG exports to China along the Northern Sea Route. While the statement in the Congress Report advocates for creating opportunities generating global and shared benefits, the development of the blue economic corridor in the Arctic has privileged bilateral relations between China and Russia.

The conceptualization of the community with a shared future fits well in the Arctic region where, besides well-defined terrestrial border systems among the Arctic States, international waters of the Central Arctic Ocean provide the chance to claim equal rights. Article 137 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), while providing legitimate rights in international waters to all parties, also fits in the community approach to global and common heritage narrative. China’s signing of the Agreement on banning illegal fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean embodies the concept of a shared future and common destiny, and shows its commitment to creating a new legal instrument to safeguard international waters where no state can exert sovereign rights.

From the economic perspective, the envision of global and shared benefits must face the new polarization of powers, which has mainly enhanced bilateral relations with Russia. On another side, it helps China improve its image as a respectful actor and its role in international politics as a contributor to the law-making process.

Multilateralism

In the first section of the 2022 Congress Report, Xi Jinping highlights how China has practised “true multilateralism […] taken a clear-cut stance against hegemonism and power politics”. He then links multilateralism with the endorsement of global governance: “China plays an active part in the reform and development of the global governance system. It pursues a vision of global governance featuring shared growth through discussion and collaboration. China upholds true multilateralism, promotes greater democracy in international relations, and works to make global governance fairer and more equitable.”14) But how is this relevant to the Arctic?

China has long strived to gain observer status within the Arctic Council. The global approach to Arctic geopolitics is deeply rooted in the global repercussions of climate change-induced phenomena happening in the Arctic. Since the 2000s, China has been improving its influence on international trade, finance and development institutions, and it also took part in international environmental treaties.15) Dynamicity in the commerce and finance fields is shown through the Silk Road Fund, the Belt and Road Initiative, the Free trade area of Asia Pacific Framework and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The ratification of the Agreement banning illegal fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean in May 2021 and the endorsement of UNCLOS as the primary legal instrument for maritime disputes in the Arctic reinforced China’s position as a supporter of the rule of law in international politics.

China’s global perspective of the Arctic and the endorsement of the legal framework are timely and in line with the shifting of the Arctic from a region with its own agenda to a region with tightened connections to a broader planetary system.16) Chinese rhetoric of endorsing multilateralism and a cooperative approach should not be underestimated. China finds itself as a legit actor in the Arctic Council, and, through the words of its special envoy Gao Feng shares skepticism about a smooth passage of the Council’s chairmanship to Norway.17)

China’s position regarding the unilateral decision to halt the work of the Arctic Council is profoundly anchored to the Arctic Council’s mandate, which does not include security matters. It is also supported by the concept of non-intervention in domestic issues. While China’s position stands for softening the hostilities with Russia, from the Arctic-7 perspective, especially from the US, it might further stigmatize China’s role in the Arctic. In the short term, as for the concept of a community with a shared future, multilateralism advocated in the Congress Report must face the new reality influenced by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. In the long-term, despite Gao Feng’s skepticism, the State Secretary Eivind Vad Petersson in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs does not share any doubt about a placid takeover of Norway of the Arctic Council’s chairmanship in May 2023.18)

This spring, we expect a new boost in reestablishing the work of the Arctic Council, where the Arctic-7 might work on lowering the tension and shifting the focus on climate change. In this context, China might keep adopting its pragmatic approach to foreign policy, on one side maintaining economic and energy cooperation with Russia and jointly working on the development of the Polar Silk Road, on the other, striving to keep participating in Arctic Council work, which is the leading way to be involved in Arctic issues.

What we have already learned is that the Arctic, rather than being a region for explicit military confrontation, is a region that mirrors the evolution of geopolitical situations happening elsewhere and where probably the governance is not appropriate to handle moments of growing tension. However, even though a normalization of the conflict in Ukraine is unlikely in the following months, climate change will be again at the center of international cooperation and multilateralism, and joint efforts are the only way to help mitigate its effects.

Conclusion

The 20th Congress of the CCP was historical in approving norm-breaking decisions. It confirmed and reinforced Xi Jinping’s leadership. While new priorities, such as national and international security, have been set over the economic development, no significant change will be adopted concerning the Arctic strategy.

The interconnectedness between producing sound scientific knowledge with the Arctic governance structure, and China’s penchant for proposing multilateral projects oriented to generate shared economic benefits, induce China to consider cooperation as an element of continuity in the region. Gao Feng’s statement in the Arctic Circle assembly resonates with China’s attempt to avoid a severe destabilization of the Arctic relations between Russia and the Arctic-7.

Sino-Russian improved energy relations and the growing presence of NATO-member states might put China in a potentially polarized sphere dimension in the Arctic. The cooperation triptych elaborates on three key elements of China’s foreign policy, which, when applied in the Arctic, reveals how cooperation remains the guiding principle of China’s Arctic engagement. Developing the maritime economy, realizing Xi Jinping’s key projects, engaging in joint scientific research and being included in Arctic governance are all interconnected aspects that push China to value and adopt cooperative behavior. Moreover, it is important to underline how the Arctic has a different priority level in Russia and China’s domestic and international politics.

So, while domestically, the renovated leading position of Xi Jinping has maybe compromised the intra-party democracy, concerning the Arctic strategy, no massive changes seem to be happening any time soon. As discussed in this article, the possibility of endorsing cooperative assets strictly depends on the evolution of the Arctic Council. The necessity for China to proceed and strengthen the cooperation triptych is important to dismantle the Cold War mentality, and to keep and enhance its position in Arctic governance as a legitimate actor with solid interests in the region.

Marco Volpe is a PhD Candidate at the University of Lapland. His main research interest regards Arctic Geopolitics with a focus on China’s Arctic Science Diplomacy.

References