How Alaska’s Proposed Pebble Mine Conflict Could Shape Future Arctic Mineral Development

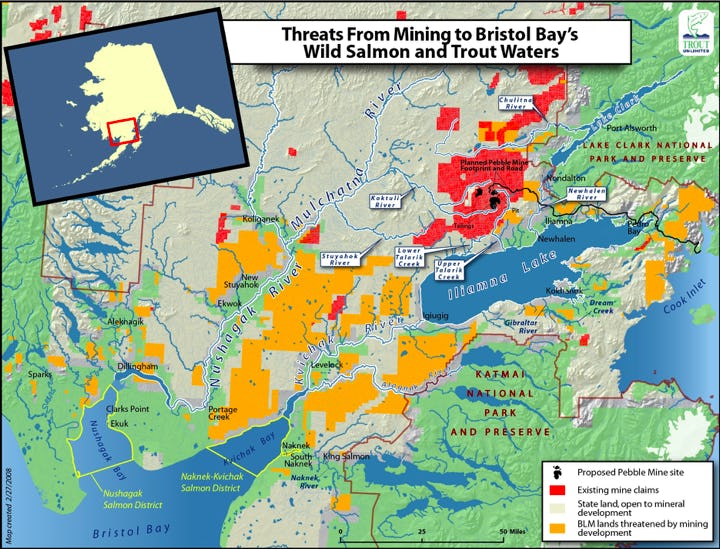

Pebble deposit directly north of Iliamna Lake. Source: Commercial Fishermen for Bristol Bay

Arctic Mining Development on the Rise

In the coming decades, Arctic nations are poised for increased mineral development. According to the Fraser Institute’s 2014 Global Mining Survey, the United States (Alaska), Canada and Finland rank in the top 10 in their annual survey of mining executives who score a country’s mineral endowment and favorable policy for attractiveness to mineral development.1) More broadly, however, the mining industry is important to all Arctic countries and the industry provides jobs and economic opportunity to Arctic regions.2) The importance of mineral development, coupled with climate change’s impacts in the Arctic, increase human activities and the related risks to the region and its people. Because of climate change, Arctic shipping lanes are open longer and the opportunity for increased port access to northern mining projects is intensified.3) For example, existing mines, like Alaska’s Red Dog Mine, will experience an increased shipping season as will new and developing projects like Canada’s Baffinland Iron Mine on Nunavut’s St. Mary’s River. Yet, as permafrost thaws and economic activity in the region expands, the risks associated with mining operations increase. Thawing permafrost is structurally weak, resulting in foundational settling that could damage infrastructure.4) Constructing and maintaining roads, railways and building structural foundations on unstable, thawing permafrost is poorly understood.5) The structural integrity of pipelines built on thawing permafrost could erode and increase the likelihood of accidents like spills. These all could have dramatic impacts on Arctic inhabitants and to fragile Arctic ecosystems.

As Arctic countries grapple with mineral development opportunities, stake-and-rights-holders who depend on healthy Arctic ecosystems must be part of the decision-making process in the lead up to, and management of, any planned Arctic mineral development. Importantly, governance structures must allow for the co-management of Arctic resources. A stakeholder-driven process can help mitigate – and even avoid – risks posed by increased Arctic mineral development and seize opportunities for stakeholder-supported projects. Shared local expert knowledge can inform decisions on potential construction impacts to important and sensitive aquatic habitat or spill response measures to pipelines or ports. When mineral development decisions are made through a community-based approach, stakeholders can trust governance decisions as objective, effective and fair and are critical to a project’s ongoing management.6) In case co-management opportunities are not provided and local support is absent, mine developers and governments could face swift opposition to the project.

One such project that did not receive local support is Alaska’s proposed Pebble Mine. Using the Pebble Mine as an example, this article highlights the challenges Arctic communities face when countries commit to increased Arctic mineral development, and policy pressure from mining companies threatens the co-management of the region’s resources. Mining companies can pressure through lobbying and public messaging to influence favorable policy and permitting, especially within countries where mineral development plays a critical role. As the potential for greater resource extraction in the Arctic becomes a reality, Pebble Mine teaches us how domestic and international actors’ pressure and shape local mining policies. It also serves as an excellent example how oftentimes disparate local stakeholders put differences aside to battle for their livelihoods and heritage.

The Pebble Mine Development Project

The proposed Pebble Mine is located in Bristol Bay in southwest Alaska. If built, Pebble Mine would be North America’s largest open-pit mine with mineral values of gold, copper and molybdenum worth over US $300 billion.7) According to preliminary plans, excavating the Pebble deposit would require 10 billion tons of toxic tailings – the removed ore once the chemical process to extract the minerals is complete – which would be stored in a tailings dam 700 feet tall (taller than the Empire State Building) in a wet, porous, and seismically active Arctic region. Hundreds of miles of road across tundra along with a new deep-water port would need to be built. Scientific documents conclude the toxic tailings and infrastructure developments could have devastating effects on the region’s watershed, especially Bristol Bay’s world-class salmon returns that depend on the region’s healthy ecosystems.8) Against the background of the scale and the potential threats from the Pebble Mine, an overwhelming majority of over 82%, of local stakeholders – including Native Alaskans, fishermen, hunters and anglers – do not support the Pebble Mine project.

Bristol Bay’s Importance: The Region, People and Natural Resources

The campaign to protect Bristol Bay from the proposed Pebble Mine reached national and international attention and has been one of President Obama’s top environmental issues over his two terms.9) In fact, President Obama visited Bristol Bay in September 2015 as part of the President’s three-day tour of Alaska to increase the understanding of climate change’s impacts to the Arctic. Bristol Bay fishermen, Native leaders and other stakeholders emphasized the region’s concerns for mineral development, especially about the proposed Pebble Mine, with the President.10)

Despite such esteemed visitors, Bristol Bay is a remote and sparsely populated region. According to the most recent census figure, its population was only 4,337 in 2010. Located in the southwest region of Alaska, roughly 190 miles from Alaska’s largest city Anchorage, Bristol Bay stretches from the rugged snow-capped peaks of the Alaska Range to the frigid waters of the Bering Sea. The northern tip of the region is roughly 550 miles south of the Article Circle. Its topography is relatively flat tundra surrounded by lakes, rivers and wetlands. Bristol Bay is considered a “national treasure” with broad acknowledgement of resources, such as salmon, caribou and bear, the region provides.11)

Native communities, spread across 31 villages, dot the Bristol Bay region, all relying on salmon to support the millennia-old subsistence culture of Native Alaskans. Bristol Bay also supports a 130 year old sustainable commercial fishery that now supplies almost half of the world’s supply of sockeye salmon.12) The headwaters of Bristol Bay’s mighty rivers, including the Nushagak, Wood, Kvichak, Naknek, Egegik, Togiak and Ugashik, is home to a prolific sport fishing industry. It draws anglers from around the world and is considered by many the nirvana for sport fishing because of the astounding returns of the prized Chinook salmon along with arctic char, grayling and rainbow trout reaching over 30 inches. For these reasons, in 1984 under the Bristol Bay Area Plan, fishing (subsistence, sport and commercial) had been listed as the state’s number one priority for resource development.13)

How Alaska’s Policies and Priorities Shifted to Favor Mineral Development in Bristol Bay

The State of Alaska selected over 100 million acres of “vacant, unappropriated, unreserved” federal lands for its own resource development as part of the Alaska Statehood Act in 1959.14) One of the State’s selection objectives was to prioritize lands with high potential for natural resource development. The State selected land in the Bristol Bay region because, among other factors, the fishery resource is of enormous subsistence and economic importance to the people of Alaska.15) Beyond the fishery resources, however, are mineral resources such as gold and copper in the Bristol Bay watershed.

The State of Alaska initially put general protective measures on Bristol Bay’s salmon resource in its 1984 Bristol Bay Area Plan (BBAP). The BBAP concluded to “close to new mineral entry those streams where highest conflict between the salmon fishery and mining would occur,”.16) At nearly the same time, in 1986, mining company Teck Cominco began mineral test sites in the Bristol Bay watershed. The company purchased the mineral claims from the State of Alaska in the area now known as the Pebble deposit north of Lake Iliamna. Other than initial drilling in 1988 and aerial surveys through 1992, Teck Cominco did little with the deposit for nearly a decade

In the early 2000’s, a small Canadian mining company named Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd. (Northern Dynasty) raised enough funds to option, and then fully purchase, the mineral claims from Teck Cominco.17) Despite the original BBAP recommending that many streams along the three main watersheds, including Lake Iliamna, be closed to mineral development, then Governor Frank Murkowski issued a new BBAP in 2005. This plan did not follow the public comment guidelines within state legislature when issuing a new Area Plan, and moved the area’s top priority for resource development to minerals and listed fishing as the last priority.18) State agencies and regulators use Alaska’s Area Plans to guide state land use decisions when considering permits for activities and development. Citizens can file a lawsuit if they believe the State did not act in accordance to Area Plan priorities. These have been largely unsuccessful in challenging the 2005 BBAP to secure protections to Bristol Bay’s sensitive aquatic habitat.

Northern Dynasty began its extensive exploration program of the Pebble deposit in 2002 and expanded the known ore resources from 1,000 million tons to 4,100 million tons by 2005, the same year Governor Murkowski changed the Bristol Bay Area Plan. By 2007, Northern Dynasty received significant financial backing from two prominent international mining companies, Mitsubishi Corporation and Rio Tinto. That same year, Northern Dynasty partnered with one of the largest mining companies in the world, Anglo American Ltd., to form a 50:50 joint partnership aimed at navigating the regulatory and permitting process by creating the Pebble Limited Partnership (Pebble Partnership). Anglo American entered the agreement by making a staged cash investment of US $1.425 billion.19) By virtue of their respective ownerships in Northern Dynasty, Mitsubishi and Rio Tinto became strategic partners and investors in the Pebble Partnership.

While the Pebble Partnership fundraised and explored the Pebble deposit, local awareness grew of the threats to Bristol Bay’s ecosystem. As previously stated, the 10 billion tons of toxic tailings, along with the risks to the region caused by building a new deep water port, culverts and hundreds of miles of road construction across tundra, greatly concerned Native populations, fishermen, anglers, environmentalists and other stakeholders. Disparate and individualized efforts attempted to outlaw large-scale mining in the Pebble area, including a 2008 ballot measure called the “Alaska Clean Water Initiative”.

The Pebble Partnership launched an extensive lobbying and public relations strategy to defeat the initiative. An estimated US $10 million was spent on advertising preceding the vote, with the majority paid for by the Pebble Partnership and its allies like the Resource Development Council for Alaska and Alaskans Against the Mining Shutdown.20) The initiative was voted down in the statewide primary election and the then-Governor Sarah Palin faced harsh criticism by voicing her opposition days before the vote, a move many called unethical.21) Palin also reportedly involved the state government to help vote the initiative down. Under the Palin Administration, the New York Times explained that “days before the vote, the Alaska Public Offices Commission found the Natural Resources Department’s Web site had improperly featured material about the referendum that favored the mining industry,”.22) It is not surprising that the Palin Administration aided in the initiative’s defeat, because as the price of copper more than doubled from 2009 to 2010, so did the value of the Pebble Mine. According to the Pebble Partnership’s documents, construction costs of the Pebble Mine alone would generate US $135 million in tax revenues for the State of Alaska (IHS Global Insight, 2013).

After the Pebble Partnership’s successful defeat of the Alaska Clean Water Initiative, the company heavily invested in its state and federal lobby efforts. From 2010 through 2015, according to the Alaska Public Offices Commission, the Pebble Partnership spent over US $1.7 million on lobbying in Alaska, including hiring the state’s top-paid lobbyist, to advance the interests of the company (Public Files).

In addition to lobby expenditures, dozens of advertisements aired throughout Alaska aimed to increase support for the Pebble Mine. After a large return of salmon in 2010, the Pebble Partnership created a cartoon television advertisement to demonstrate how mining along British Columbia’s Fraser River could coexist with salmon populations. However, after disastrous returns to the Fraser River thereafter, coupled with the Mt. Polley tailings dam breach into the Fraser River in 2014, the Pebble Partnership has yet to air the advertisement again. The original advertisement has been taken down from the Pebble Partnership’s website, however, an edited version that also highlights the Mt. Polley disaster can be viewed here.

Save Bristol Bay: A New Coalition Targeting a Federal Solution to Stop Pebble Mine

After the Alaska Clean Water Initiative was defeated in 2008, Bristol Bay stakeholders began to strengthen their coalition given their concern about the mine’s probability of contaminating waters within the Bristol Bay ecosystem. Moreover, the state’s collusion and the US $300 billion dollar value of Pebble Mine underscored the zero sum game between those who depend on salmon for commercial, subsistence and recreational purposes and those wanting to reap the rewards of building one of the largest mines in the world. The battle for Bristol Bay reached critical heights and the Save Bristol Bay coalition took shape.23) Trout Unlimited, a non-profit hunting and freshwater angling organization, acts as the coalition’s primary organizer (Save Bristol Bay). The coalition includes various stakeholder organizations such as the Bristol Bay Native Corporation (BBNC), Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association (BBRSDA), United Tribes of Bristol Bay (UTBB) and the Natural Resource Defense Council (NRDC).

Of the 67 permits the Pebble Partnership needs to acquire to advance Pebble Mine through the permitting process, 66 are state level permits and one is federal. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources, the lead agency for mineral development and exploration, is guided by the statute to prefer land use that “will be of the greatest economic benefit to the state and the development of its resources,”.24) Although design changes are often required throughout the permitting process, because of this statute, a large mine project that has begun the permitting process has never been rejected by the State of Alaska.25) The open-ended procedure means the company can keep responding to agency questions. In fact, officials from Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources are on record stating, “if the company can meet all the standards in their design, we may have no choice but to permit them […,] essentially they are due a permit. As long as they keep beefing up the design, at some point you’d think we’d have no choice,”.26) These issues together raise the unease about the effectiveness of input and concerns from local stakeholders on mining projects in Alaska. In sum, due to the ineffectiveness of finding a state solution to protect regional interests and Bristol Bay’s ecosystem, regional stakeholder groups decided to find a federal solution to stop Pebble Mine.

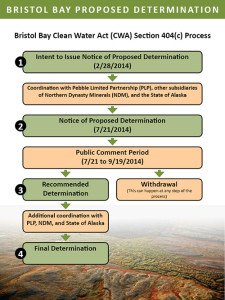

The State of Alaska’s almost-guaranteed approval of the necessary state-level permits required a strategy reorientation. Thus, the Save Bristol Bay campaign focused its efforts on the one federal permit the Pebble Partnership needs to build Pebble Mine. The federal permit needed is a 404 dredge and fill permit. Under the Clean Water Act, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority to step in front of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (who issues 404(c) permits) and veto or restrict a 404 permit for dredge and fill discharge if it “is having or will have an ‘unacceptable adverse effect’ on municipal water supplies, shellfish beds and fishery areas (including spawning and breeding areas), wildlife, or recreational areas,”.27) Since its inception, the EPA has issued a restrictive or 404(c) veto thirteen times and only once preemptively before a mining permit has been filed. Because the Pebble Partnership has not filed for its federal 404(c) permit, the EPA would need to rely on mining plans submitted by the company to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to assess whether a mine like the Pebble Mine would cause adverse impacts on Bristol Bay’s habitat.28) As previously stated, the EPA has precedence to issue a preemptive 404(c) ruling, and a restriction or veto would severely hamper the permitting and construction of the Pebble Mine.

Because the State of Alaska failed to act upon the concerns of its local residents, in 2010, almost halfway through President Obama’s first term, six federally recognized tribes (which later grew to nine) petitioned the EPA to initiate the 404(c) review process for dredge and fill permits for the Pebble Mine.29) Similarly, other groups like commercial fishermen, sport fishermen, Bristol Bay Native Corporation and environmentalists weighed in requesting the EPA for a 404(c) decision. Stakeholders voiced concern that large-scale mining would affect, among many important environmental factors, salmon rearing and spawning grounds that jeopardize their subsistence, sport and commercial fishing activities.30)

Pebble Partnership’s Stall Tactics and Public Support to Protect Bristol Bay

After the 404(c) petitions were filed, the EPA agreed to conduct a watershed assessment of Bristol Bay to assess potential impacts on the water quality if a mine like Pebble were to be developed. The results, through a public and peer reviewed science-based process, were unequivocal. The first assessment was released in April 2012 and issued concerns that large-scale open-pit mining activity like that of the proposed Pebble Mine would cause adverse habitat impacts on the salmon systems.31) The second draft assessment was released in May 2013 and included public input and peer review from the first draft and issued similar conclusions.32)

For nearly a decade, a string of broken promises and stall tactics from the Pebble Partnership to file for federal dredge and fill permits, which would therefore trigger the federal permitting scheme increased anxiety, confusion and frustration in the communities.33) Originally, the Pebble Partnership sought to complete a prefeasibility study for the Pebble deposit by late 2008, a feasibility study by 2011 and commencement of commercial production by 2015.34) As of January 2016, the Pebble Partnership has yet to submit even a prefeasibility study. Instead of issuing its feasibility studies to the EPA and any additional scientific analysis demonstrating Pebble Mine would have no adverse impacts on Bristol Bay’s ecosystem, the Pebble Partnership engaged in heavy lobby and public relations tactics. These tactics helped prompt Congressional hearings and the company issued subpoena requests between Save Bristol Bay coalition leaders and the EPA. These efforts could stall the federal permitting system or discredit the EPA’s Watershed Assessments altogether as biased. By stalling its 404(c) permit filing, the Pebble Partnership could file in a more favorable political environment. Or, by discrediting the EPA’s Watershed Assessment altogether, the Agency’s authority to veto or restrict the permit might face serious legal complications.

Despite the Pebble Partnership’s attempts to persuade the public and decision-makers about the project, support for the project waned. Decision-makers on Capitol Hill and federal agencies like the EPA received an outpouring of support for a Clean Water Act 404(c) action as over one million public comments were filed between the two Bristol Bay Watershed Assessments.35) Celebrity chefs, jewelers like Tiffany’s, thousands of fishermen nationwide, and prominent elected officials like Senators Mark Begich and Maria Cantwell all spoke out against the project.

The EPA’s imminent 404(c) action, coupled with national public support to protect Bristol Bay, increased the uncertainty as to whether or not the project could be conducted. Pebble Mine’s financers all grew wary of the project and its potential damage to their bottom lines and international images. In a testament to the David versus Goliath scenario, by early 2014 all three partners (Mitsubishi, Anglo American and Rio Tinto) abandoned their stakes in either the Pebble Partnership or Northern Dynasty. The final partner to pull out, Anglo American Ltd., wrote off a self declared US $543 million loss and left Northern Dynasty without any backers.36) But the potential to develop Pebble Mine still stands. The Pebble Partnership, now consisting only of Northern Dynasty, still owns the mining rights to the Pebble deposit and all research previously conducted.

After its final assessment was released in January 2014, the EPA began its process of issuing a restrictive 404(c). By filing intent for a 404(c) in February 2014, the EPA allowed the State of Alaska and Pebble Partnership to respond in 90 days with any new evidence that Pebble Mine will not cause adverse habitat impacts on the Nushagak and Kvichak watersheds.37) No such evidence was ever provided.

Since the EPA began its 404(c) process, the Pebble Partnership has employed numerous tactics to stall the process. These tactics have had various levels of success. U.S. District Court Judge Russel Holland dismissed the Pebble Partnership’s subpoena request to disclose private communications between anti-mining groups and the EPA. Local stakeholders hailed the court’s decision to defend their constitutional freedom of speech rights and that fishermen, Native Alaskans and other stakeholders should be able to communicate with the government without large multinational companies using scare tactics to request private documents and personal communications.38)

In June 2015 after a court challenge by the Pebble Partnership, Judge Holland ruled it “plausible” that the EPA improperly “utilized” input from opponents of the Pebble Mine.39) Judge Holland dismissed three other claims by the company but allowed this portion to proceed, and has issued a temporary injunction on the EPA’s 404(c) process until a conclusion is made. This tactic is an attempt to discredit the EPA’s Watershed Assessments as biased and potentially impact the Agency’s 404(c) authority of the proposed Pebble Mine. However, on January 13, 2016 the EPA’s Inspector General issued a report finding no evidence of bias in the EPA’s draft determination.40) Therefore, a decision by Judge Holland could be any day. The temporary injunction by Judge Holland stopped the EPA to issue a recommended determination as shown in the adjoining diagram, Step 3.

Beyond Bristol Bay – Solutions for Arctic Mineral Development

Local mining policies vary throughout the Arctic, but in any case an Arctic nation’s commitment to increased mineral development must be coupled with a commitment to co-manage the region’s resources with local stake-and-rights holders. Mineral development can benefit local economies but must not destroy important ecosystems in the process. The Pebble Partnership and its financers show how mining companies can be effective at advancing their agendas to solely advance their economic interests to the detriment of important ecosystems and the people who rely on healthy environments. The Save Bristol Bay coalition members identified a common threat and coalesced around scientific evidence that concludes Pebble Mine will have devastating impacts on Bristol Bay’s ecosystem.41) In order to bring change to the domestic policy agenda, the coalition used scientific evidence to inform the public and decision makers on the risks and uncertainties associated with building North America’s largest proposed open-pit mine at the headwaters of the world’s largest salmon fishery. Therefore, even more importantly, the Save Bristol Bay campaign demonstrates the effectiveness of local stakeholders coalescing to bring change in the face of entrenched pro-mining policies and the deep pockets of mining conglomerates.

The Save Bristol Bay coalition and its central issue of whether to allow large-scale mining activity in Bristol Bay can help inform future civil society coalitions as to how to amplify their influence in sustainable development decision-making processes. And as Arctic nations balance the need for jobs and economic development through natural resource extraction, Bristol Bay and the proposed Pebble Mine teach us how economic policy should not damage environmental security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not the opinion of Seafood Harvesters of America.

References